When I woke up in the middle of the night, I noticed that Jeffrey was not next to me. His side of the bed was clean and made. As I snuck down the stairs, I could see him asleep on the sofa, a pillow crammed under his head. I got the familiar feeling in the pit of my stomach of having done something wrong. I had put on a lace nightgown last night just in case, but it hadn’t mattered. Jeffrey hadn’t seen me. I could walk around like a nudist and it wouldn’t even register with him. Now, when I returned home from my morning walk, the sofa was empty and I folded the blanket that he had tossed aside. There was no point in being melodramatic.

The club phone directory lay open on the counter. I stood above it and ran my fingers along the numbers. I flipped the pages, closed my eyes, and pointed.

Tuck. I wasn’t going to call him. He’d recognize my voice, tell someone. I closed my eyes and chose again. I didn’t recognize the name and I dialed *67 to block my number, then I took extra care dialing, listening to the beep with each numeral. I listened to the phone ring and when a man picked up, I said a breathy hello, waited for a return of the favor, and got nothing. He hung up. That was the problem. Often I was mistaken for a telemarketer or someone begging to change political parties. I wasn’t. I just wanted to get us off.

I tried to phone my mother. It rang and rang, with no answer, not even a voice mail or a machine picking up. I considered driving over to see her, just to see if she was okay. I decided I would do it after another walk. I needed to clear my head and think of how I would approach her. I knew she wouldn’t be happy to see me. The last time I had seen her I’d told her I was ashamed of her. I used to watch my mother float through the house at night in her lace see-through nightgown, unashamed as we watched her. She was the most beautiful woman in the world to us. We wanted to be womanly like she was. I wanted to be looked at and desired. As I had been gangly and young, it had seemed to me an impossibility. I’d had to wait years to fill out.

She was always pacing and waiting for our father, but she looked so gentle floating back and forth, her nightgown billowing behind her with each step. Her heels would tap against the wood floor and hypnotize us with the sound. When she wasn’t home, we’d take her heels out of the closet and try to mimic that sound as we paced and puffed on invisible cigarettes, looking out the window for our father, trying to capture that same exasperation. When our father stopped coming home, she took to waiting for other people’s fathers, but we didn’t wait with her then.

There were times when the men would bring us food and we’d be fed for a while. But sometimes she would be gone for days and we’d have to search the house for spare change or for some of the rolled-up money we saw them give her when they thought we weren’t watching. We’d take it, knowing she would always get more, then run to the store and stock up on TV dinners, breakfast setups with smiling parents on the packages, frozen treats we wouldn’t save for dessert. When she was home, she’d prepare a feast of whatever she had. She made it feel elaborate and special. Once, she had come home with a watermelon, exclaiming it was too hot to eat anything else. She cupped a melon baller and dipped it in and out of the flesh of the watermelon, making a hillside of sticky red balls on a plate. She cut out stars to put on top of the overflowing plate. She said we could eat it all; it would fill us up. Then she gave us each a cube with a dusting of salt and told us to pretend it was the main course, the rest could be dessert. Juice flowing down our chins, we ate until our stomachs rumbled, sick from the sweetness. She said some people never got to taste watermelon even once in their lives and we got to eat one whole.

My mother always dyed her hair a brassy blond and when she wasn’t entertaining, she put it up in curlers with a thin, gauzy scarf wrapped around it. But when she unwrapped the curlers and pulled her fingers through the loose waves, she looked beautiful. Her face never betrayed her sadness about being abandoned or about our sister Laurel, who had died before she even turned two. Her slender calves and shapely hips filled in her dresses just so as she wandered the house night after night. As I got older, I would put on the laciest of her bras and imagine taking them off for someone. I kept my hair long and blond, not as bright as hers was, though. I had her body everywhere and displayed it casually, like it would always be perky for me. I was happy that I had studied her femininity well enough to capture it. But I was no longer making use of it. The subtle, daily humiliations had finally taken their toll on me because nothing I tried worked any longer.

When our father left, our old rotary phone would ring and my sisters and I would fight like rabid dogs over who would answer it, hoping it was him, but it never was. My sisters spent less and less time at home, wanting to be away from all the sadness, the outline of missing people too grim. Boys would take them away, my mother would yell, warning them they’d end up like her, alone with a brood of ungrateful girls of their own, but they didn’t listen. Neither did I.

I remember the thrill of hearing my first feverish call—a man breathing into the phone, asking for Roberta. We would hang up on them and run away, or sometimes, if the phone would ring and ring, we’d leave it off the hook. Our mother would chase us around then, calling us brats and worse. But the phone kept ringing and I started picking it up and I wouldn’t hang up when I heard the begging voices. Instead, I’d let my voice go gravelly and low and I would ask them what they wanted exactly, then I would try to give it to them. Sometimes they wanted me to laugh in their ear, sometimes they wanted me to tell them what my dreams were, sometimes they just wanted to know what I’d do if we were alone in a room together. I would wrap and unwrap the phone cord around my index finger and watch it go red, the blood just under the skin wanting to burst out. Sometimes, my mother would follow the cord and I could feel the tug as she picked it up and walked with it down the hall and into the pantry, where I was hiding and whispering about my see-through panties. She’d yell at me, but I would run, and eventually, they only called for me. I had to leave then, as our resentments became unbearable and the house became a tomb to everything we had lost.

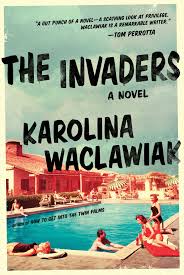

From THE INVADERS. Used with permission of Regan Arts. Copyright © 2015 by Karolina Waclawiak.