The Intoxicating Other Worlds of the Encyclopedia

David Carlin on Absent Fathers and Missing Histories

One hot summer when I was ten and the holidays stretched out endlessly, I stayed inside for a whole week to devour The Lord of the Rings end to end, lying on the loungeroom carpet. Tolkien made a world that seemed so vast and whole it was possible to dwell inside it like it was a giant cocoon. Ursula K. Le Guin managed a similar feat with the Earthsea trilogy. C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books likewise. As a child, one wasn’t concerned with whatever authorial ideologies might underpin the logic of these worlds. I just thought Aslan was a very wise lion.

It was the worldness that mattered; that dual sense of completeness and infinite extension. But for worldness, nothing quite compared to the gleaming row of books that occupied half our bookshelf: the 22-volume set of World Book Encyclopedia. This was the 1970s. Before the Internet. I lived in Perth, Western Australia, which felt far away from everywhere and everything. I knew the whole world wasn’t really contained in those 22 volumes from A to Z, but I loved the idea that it could be.

Why love the encyclopedic? What is the joy and madness of this desire to encapsulate what is most important to be known? From Pliny and Diderot to Wikipedia, encyclopedias have served myriad functions, but, as with Tolkien or Le Guin, or the people behind World of Warcraft, they constitute a world-making activity as much as a window onto a world out there.

The more you know about anything the more an encyclopedia is fated to disappoint you.

Encyclopedias, at least of the analog variety, although sold as containing all the things one ought to know, are testament to the futility of that idea. As soon as you open one you are looking for what is missing. I distinctly remember as a child being conscious of how few pages the World Book dedicated to the entry for Australia, especially compared to its near neighbors Alabama and Arkansas. I knew already that was silly. I knew that Delaware was given attention out of all proportion. (As I write this I wonder: does Delaware still exist? Until I remember it must because we are told Joe Biden lives there.)

The more you know about anything the more an encyclopedia is fated to disappoint you when its restless searchlight briefly illuminates that topic. I believe a picture of some sheep illustrated the concept of Australia. Maybe accessorized with a white man on a horse, and a fence. You could tell that the people who put together the World Book didn’t know much about Australia. They didn’t know about the feeling of hot sand under your feet, how the breeze from the ocean could suddenly spring up, the smell of peppermint trees. They didn’t know about the way the bore water stained the footpaths (a Perth thing). Even the facts they crammed into each paragraph were noticeable for the violence of their concision. One paragraph might be allotted for fifty years of history. Another paragraph for culture (white), one for sport. Or maybe two for sport because after all it is Australia (Cuthbert, Laver, Bradman).

The masterpieces of the 1970s World Book were its pages of layered plastic transparencies. There would be four or five of these overlain, designed to show the intricate complexities of an object deemed of high significance, like the human body or the geology of Delaware. There was always something magically unpredictable about which elements of the compound image would peel off in each layer. Individually they didn’t make much sense, but together they conjured an apparition. A bit like each volume in the set.

From the many hours I spent alone with the World Book, I retained such vital information as the names of all 50 states of the USA (which I can still recite in a crisis). I learnt capital city, length of river, and height of mountain facts. The world, I learnt, had names all over it, and its many features were available to be measured. But most of all I learnt that he [sic] who writes the book decides whether Delaware or Delhi or deliquescence or Casey Delacqua (look her up, ye non-Australians) is more worthy of attention. The execution of an encyclopedic impulse always tells you more about the people making it and the culture they come out of, than it does about the world of objects and subjects it is claiming to make known. To see this is true you only have to examine an encyclopaedia from another time and place.

The curious and disturbing wonder of encyclopedias is their deadpan quality.

We have an old Pears Cyclopaedia from 1933, which I found in a secondhand bookstore. It was hugely popular at the time; enough copies had been sold to fill seventy-seven miles of bookshelves, as it tells you on page two. It is divided into sections for the Business Man, the Schoolboy, the Student, and the Woman: for the former, a Gazetteer of the World, Atlas, Dictionary and so on; for the Schoolboy, useful knowledge relating to History, Science, Music, Architecture, Classical Mythology, etc.; while for the Woman, naturally enough, the sum of topics are The Toilet, Cookery, Medical, and Baby’s First Year. Certain topics are for whoever might be interested, such as Gardening and Domestic Pets, under which it includes, surprisingly, Monkeys, Rats and Mice. Under the heading of The Toilet can be found information (for the Woman) on Superfluous Fat, Falling Hair, Lines (“see Wrinkles”), and Curling Fluids (but not Menopause, Menstruation or Clitoral Stimulation). I suppose the emphasis on the aforementioned Toilet can be explained by Pears’ primary business in making soaps and powders. Their motto, advertised at the back of the book: the aid to natural charm. World Book would never stoop so low.

The curious and disturbing wonder of encyclopedias is their deadpan quality. Like the archetypal stern schoolmaster, they are not big on jokes. (Wikipedia differs here, as it does in so many other ways, because it is open to being hacked by pranksters.) Blind catalogues of other stories they are hiding or eliding, encyclopedias can’t or won’t fess up to the blinkers they are wearing. Neither the rose-colored glasses, nor the telescope myopically fixed to one eye. It’s a safe bet that the 1970s-era World Book’s entry for Australia does not mention many of the most basic facts relevant to this landmass, starting with that the sovereignty of over 250 Indigenous language groups of the world’s longest living cultures has never been ceded. That over 250 documented massacres of Indigenous people took place at the hands of the European invaders between 1788 and 1928. That Indigenous people were 13 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Indigenous Australians in 2000, and this had risen to 17 times more likely by 2008.

The artist Ali Gumillya Baker, a Mirning woman from the Nullarbor on the West Coast of South Australia, exhibited an artwork in 2017 at the “Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism” exhibition at ACCA, Melbourne, called “Racist Texts.” It takes the form of a single, endless stack of books placed one atop the other, spines out, wedged floor to ceiling. A representative slice of Australian nonfiction and fiction, the unexceptional texts reflecting White Australia back to itself through all the ways it could be known—its history, biology, zoology, folklore, while, oops!—leaving out all trace of the violence against Indigenous people it was predicated on.

Baker’s work can be read as a spanner in the encyclopedic works. Set conceptually against the horizontal shelves of orderly, leather-bound tomes that formed a key, aspirational possession of the Enlightened European, here is a defiantly interrupting vertical stack, eschewing the alphabetical and extending metaphorically far beyond the boundaries of any room. It confronts the white Australian viewer by radically re-categorizing books that hitherto may have seemed so “innocently,” plainly factual.

*

If the most important lesson the World Book taught me was that I was not American, that I lived not at the center of the world but on its margins; nevertheless, because I was white and a boy, the World Book offered plausible advice about what the world could turn out to be like for me. The American it was written for—or written around—was also white and a boy. This didn’t have to be said out loud. Every book constructs its reader. Encyclopedias construct masters: polymaths. If you were white and a boy you could start to build a sense of who you were and who you could be in relation to the world, and moreover what the world was in relation to you. Like the classic proscenium arch theatre designed around and for the perfectly positioned singular perspective of the monarch, the popular encyclopedia of the 19th and 20th centuries laid out an array of objects and subjects, selected through all the major Western knowledge disciplines, precisely for my supposed benefit; the pale young boy apprentice to this mastery.

Because I was white and a boy, the World Book offered plausible advice about what the world could turn out to be like for me.

But I always had an ambivalent relationship with mastery. On the one hand I could perform my fifty states party-trick, and even now I can also recite the list of which teams won the premiership of the Australian Football League going all the way back to 1980 (1969 in a pinch). I like to think I know a little bit about almost everything. About Ethiopian emperors. About dental hygiene. About the history of the London Underground, and the system of house numbering in Venice. About what haunted W. G. Sebald and his writing, about people-trafficking in West Timor; how to craft the foot of a ceramic bowl. About theories of bullshit jobs, the neoliberal imperatives of contemporary universities; about memory and trauma and mental illness and the things that you inherit; about what it means to inherit; about how Charles Darwin liked to spend his days (a lot of walking); about Gilles Deleuze’s rhizomes, Judith Butler’s performance of gender, and Anna Tsing’s paradoxical ruined forests where the fungi thrive, about circus tricks and apparati, the difference between a cloudswing and a tissu, about the films of Alfred Hitchcock, the caravan parks in and around Broken Hill, vegetarian cooking, the literary politics of Indonesia, what an essay is and how to write one. I could keep going forever listing things I know a little bit about. I like the feeling of knowing a little bit about a lot of things; maybe this is the encyclopedic urge. But I’m a recidivist hazy sketcher. Jack of all encyclopedia entries; master of none.

Now I gravitate to the essay because it welcomes doubt.

It could be that as a child I sought the comfort of an all-knowing entity as a proxy for my absent father. If the World Book was flawed, nevertheless I could appreciate the fantasy it represented. It could keep me company in my unknowing: why was my father dead and why must this question never be asked? Why was nothing ever said of him and why did the world proceed all around as if nothing was amiss? This was evidently how the fabric of the world was made: from silences. I learnt a lesson then about seams and cracks; they might be staring you in the face, but it wouldn’t mean you saw them.

The one concept the World Book would never introduce to me was suicide. That must never be allowed to come into my mind or into the pages of my reference books. Fathers, in symbolic terms, were masters of the universe, white fathers above all. But not mine. Everyone said he was a “good man,” and yet beyond that he was literally unspeakable. His resistance, as I found out much later, took the form of rejection of his own father’s masculinist precedent, a questing for consolation in the face of violence, and in the end a heartbroken, desperate retreat when told the only treatment option remaining in 1964, according to the latest medical knowledge of human mental illness, was a Freeman frontal lobe lobotomy.

A is for Arkansas, but you pronounce it Arkansaw (that is something new I learned just now from the new encyclopedia plus ultra that is Google).

D is for Disney (Wonderful World of). Because our Sunday nights were also colonized.

E is for eternity, the time before we are born and after we die, and the short, encyclopedic flurry in between.

Meanwhile U is for Unthinking. In the book Unthinking Mastery by scholar Julietta Singh, she notes that wherever a story creates masters it also creates slaves.

____________________________________________

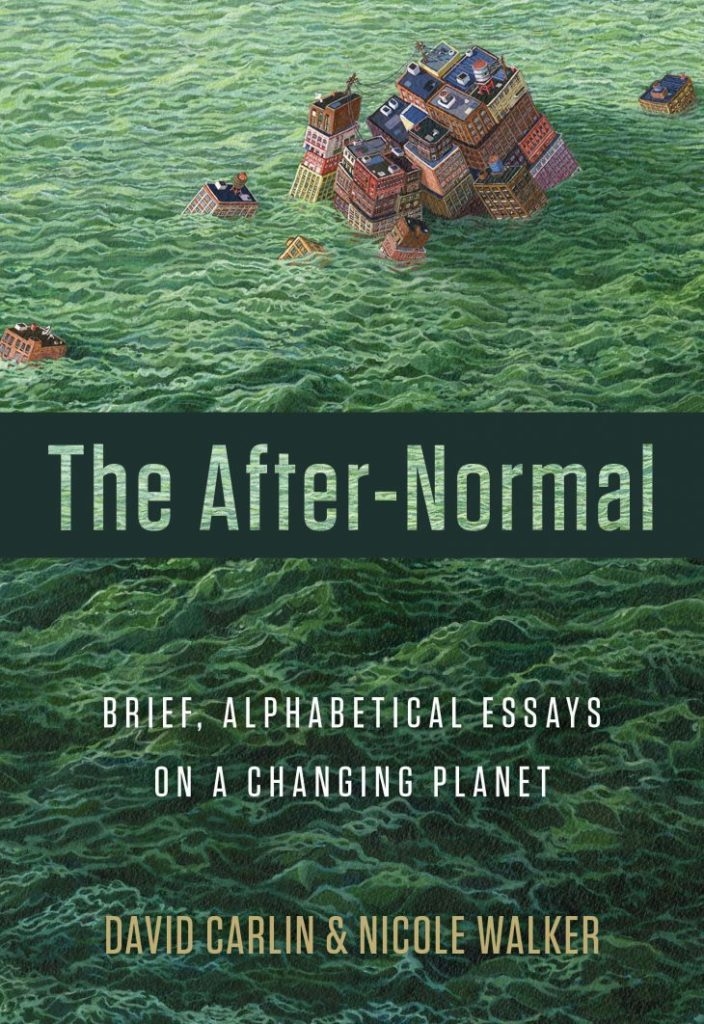

David Carlin’s The After-Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays On A Changing Planet is now available from Rose Metal Press.

David Carlin

David Carlin is a writer and creative artist based in Melbourne, Australia. He is the author of The Abyssinian Contortionist (2015), and Our Father Who Wasn’t There (2010), co-author of 100 Atmospheres: Studies in Scale and Wonder (2019), and the editor, with Francesca Rendle-Short, of an anthology of new Asian and Australian writing, The Near and the Far (2016). His award-winning work includes essays, plays, radio features, exhibitions, documentary, and short films. He is a professor of creative writing at RMIT University where he co-directs the non/fictionLab. Most recently he co-wrote The After-Normal with Nicole Walker.