The Interview That Adrienne Rich Never Wanted Published

Patrice Vecchione on Talking with Rich About Spirituality

We were together in the sound-proofed radio booth with the door shut, Adrienne Rich and me. Outside the room, above the door, lit in neon, were the bright red words “ON AIR.” It was a Sunday evening in October in 1998 when then-independent public radio station KAZU’s live poetry show, Ars Poetica, aired. Adrienne and I were the only ones at the station, adding to the intimacy of being in a small room together. I was guest host for the show and Rich had driven an hour south from her Santa Cruz home to the small city of Pacific Grove.

We were there to publicize both her new book of poems, Midnight Salvage, and an upcoming poetry reading that she and I were helping to coordinate, sponsored by the local branch of the National Writers Union, titled “Claiming Our Voices in This Land of Immigrants.” Jimmy Santiago Baca, Marilyn Chin, and Quincey Troupe were coming from out of town and local writers were participating too. Before we began the interview, I slipped a cassette into the tape deck to record it.

By then, Rich and I had known each other for about 15 years and, though not friends, there was a warmth between us whenever we met socially or to work together on literary projects. She often participated in a benefit reading series that I co-coordinated for many years, “In Celebration of the Women: Women Writers Reading.” When I wanted to include one of her poems in a young adult anthology I was editing, she contacted W.W. Norton to ask her publisher to reduce the fee for my low-budget book. As one who stood wholly in support of the voiceless claiming their voices, she was supportive of my teaching poetry to children. Rich brought me in to help with the gala when she was named Santa Cruz County Artist of the Year in 1995. Still, she was Adrienne Rich, so on that October 1998 evening I was nervous, particularly because there were a few questions I wanted to ask her that I feared she might not welcome.

During the many years she lived in Santa Cruz, when we’d meet, it was both sweet—how she’d take me in her arms for a quick, close hug—and sad—Rich was impaired by rheumatoid arthritis, the disease that later took her life, her hands becoming more claw-like and her movements more difficult and limited as time went by. The older she got and the more her condition worsened, even her smile had a pained look to it, but never did I hear her complain.

One day at an oceanside restaurant for lunch, in the mid-90s, when she took me out to celebrate my recovery from surgery, Rich expressed curiosity about how excited I was for the day when I could get back to distance bicycling. She was curious about the counting strategy I used when energy flagged and wanted to know what bonking was like (when a rider hasn’t eaten enough and experiences abnormally low glucose levels and can’t think clearly). Really, I think it was just how active I was that captivated her—she was in her mid-sixties and I was in my late thirties. (Not surprisingly, the memory of the vigor of my life then captivates me now too.)

Rich replied, “Well, I think writing is my spiritual self,” with a little chuckle.

Over the years that I knew her, her physical pain was accompanied by emotional pain; not so much for herself, but Rich’s acute awareness of the world’s injustices mixed with abundant empathy caused her to be deeply burdened. She felt an undeniable obligation to give her attention to the disenfranchised in her writing. Rich seemed to be someone for whom there was no separation between self, work, and politics.

In 1997 Rich refused to accept the National Medal of Arts when President Clinton offered it to her because of the administration’s “cynical policies,” saying, “The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A president cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.” Imagine what she’d say today.

Rich saw art as a vehicle to help bring about societal change. I admired her conviction, even if I saw (and see) art’s purpose a little differently. How often my students—kids and adults—sit before a piece of blank paper, unsure of what they’ll say, until the words (sometimes accompanied by tears) come, and at the end of the poem there isn’t only a period and a sigh of recognition but a smile that’s the result of having said the unplanned thing. Societal change can begin one person at a time.

Especially during the first years that I knew Rich, I thought that my own poems were far too personal, addressing the small stories of what it means to be alive, for her taste. Spending time with her only reinforced my long-held belief that I wasn’t up to snuff. (I’m sure she never intended for me to feel that way.) But those feelings didn’t stop me from revering both her being and her writing; nor did they stop me from writing and making art.

Years before Rich and I knew each other, I admired her poetry and resonated with and felt gratitude for her feminism. And during the worst period in my life, Rich’s work helped me to find my way.

It was when I was in high school that I’d begun writing poetry—mostly outside of class—leaning against a classroom building or huddled in my bedroom late at night. It was the one liberating thing in my life. Writing poems, no matter how lousy they were, helped me begin to gain independence from a difficult home life, to see myself and my life with some degree of clarity.

In those days—the early 1980s—I couldn’t afford to buy hardback books, but in the case of Rich’s book The Will to Change, I made an expensive exception. It was my need of poetry and my feelings for Adrienne Rich as a poet that made me want the book but, more than that, it was the title. A will to change was exactly what I needed. I hoped the poems might lead me to find such willpower of my own. I turned to the title poem once I got home, maybe before that. And though the poem was hard for me to make sense of in its entirety, there were two lines that made my breath stop, lines that have resonated with many and been quoted often: “We’re living through a time / that needs to be lived through us.” Rich may have meant “time” in a large way but I applied it to my own life. Perhaps, I reasoned, I would live through this time and get to something better; I didn’t think it could get much worse.

And later in that long poem, a single line from its fourth part, “from the Feast of San Gennaro,” also hit home but in an entirely different way. I knew the Feast of San Gennaro as I knew other Italian feast days from growing up in a strong, culturally identified New York City Italian family. Perhaps I could bring my past along with me, and honor parts of it by drawing on my experiences, and by using my will to change I could create a sustainable and creative, poetry-infused future for myself, one that didn’t include the parts that were holding me back.

In 1984, shortly after Rich moved to Santa Cruz, I had my first chance to introduce her to an audience. I told the large group gathered for “In Celebration of the Muse” how important The Will to Change had been to me, how it had been my catalyst for change. The woman poet pictured on the back jacket had found her will and, with the help of her poems, I had found mine. That evening, Rich signed the book for me, “in sisterhood,” in this small but consequential way bringing me into the fold with her and other will-bearing, determined women.

And there was something else when Rich and I met that reinforced her importance to me. I was then in a relationship—wholly in love—with another woman. Rich was a role model for me, which was especially valuable since my mother had disowned me for my choice of partner. Rich was an older, sober, successful, feminist woman who had found her way in life with poetry. Could I?

*

Back at the radio station, after we told the radio listeners about our upcoming benefit, we began to chat about poetry and creativity. At the time of the interview I was working on a book proposal for what became Writing and the Spiritual Life: Finding Your Voice by Looking Within. That book was very much on my mind and I hoped Rich might talk with me about writing and spirituality. I knew that because she self-identified as secular, she might not wish to respond, but I sensed spirituality in many of her poems.

I asked Rich what it was she found in poetry and, before giving her a chance to answer, suggested that it was soul. “If I had to find one word,” she responded, “that’s what I would choose.” Her answer encouraged me to go further.

Previously, in our private conversations, if I directed us toward talking about spirituality, she immediately changed the subject. Rich hadn’t been responsive to my anthologies that addressed spirituality. My sense was that Rich would not address it directly.

In a 1987 talk that Rich gave at the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco, she had said, “I think there are some of us who are drawing a deep sustenance from Jewish secular progressive tradition, who are trying to fuse the material with the spiritual rather than leave them in the old dichotomous opposition. . . . Maybe we don’t know exactly what we are trying to do nor yet have a language for it.”

That night at the radio station, Rich was in the guest’s chair while I sat behind the soundboard, monitoring levels, reading public service announcements, and talking with her. She was radiant that evening, appearing at ease and happy to be chatting together. Listening to the interview again today, that’s what comes through in her voice.

After agreeing with me that soul is what’s found in poetry, Rich went on to say, “But it’s also I think courage, it’s a recognition of beauty in the midst of recognizing perhaps the worst, facing the true terrible stories of our time, of our lives, and finding that in the very expression of them, in the very representation of them, there is an extraordinary beauty and power. And that as we speak out of the terrible truths that we all know, we are touching a kind of power that is not very much . . . it’s not very much credited in the public sphere; but it’s there, it’s there for us to find.”

It was midway through the interview, after we’d spoken at length about her new book, that I took a deep breath and hesitantly asked the question that I most feared would be unwelcome, “I guess, my question really is, what is the connection for you between writing and your spiritual self?”

Rich replied, “Well, I think writing is my spiritual self,” with a little chuckle. “I think that the creative act and also the receiving of the creative acts of others, the receiving of poems, of works of art in any medium by others that speak to us, that’s a spiritual life. I don’t see myself seek any other. I once described myself as a secular Jew and someone said, ‘Oh, reading your poetry I don’t see how you can call yourself secular.’ But, um, I was using the term secular in contrary distinction to religious in the institutional organized sense. But, yes, poetry is a spiritual life.”

I wish she’d just called; that’s all it would have taken for me to honor her request, but maybe she would have found that to be too difficult.

About a week later, a letter addressed to me in Rich’s distinctive hand arrived. I was surprised to hear from her so soon. The typed letter was curt and to the point. She said, in no uncertain terms, that I was not to publish anything she’d said nor to publicly reference details of the interview or I would hear from her attorney.

Reading the letter, I felt sick. Not so much because I couldn’t use the material but because she had written such a formal letter. I wish she’d just called; that’s all it would have taken for me to honor her request, but maybe she would have found that to be too difficult.

When Writing and the Spiritual Life came out in 1999, Rich went out of her way to praise my work. In an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle she called me “one of those steady, vibrant, serious and passionate temperaments who continually replenish our sense of communal creativity. In my country of possibility, she and people like her would be nationally honored figures,” which surprised me greatly.

Now, nearly ten years after her death, I see no reason to keep the contents of the interview private any longer. I think what she told me that October evening during our radio interview was true and adds a kind of welcome complexity to her better-known secularity and political militancy—without taking anything away from them. After receiving that letter, though we maintained a professional relationship and though she gave me that beautiful quote for my book when it came out, I kept myself at a remove from Rich and didn’t attend her readings that previously I’d have rushed to.

If such a letter were to arrive in my mailbox today, at sixty-two years of age, I know better what I’d need to do. I’d call her up right away, and the ensuing conversation would be healing for us both. But twenty years ago, Rich’s uncourteous words simply shut me up, just as she’d intended them to. Though that letter distanced me from her, not for a moment did it take her poetry away.

__________________________________

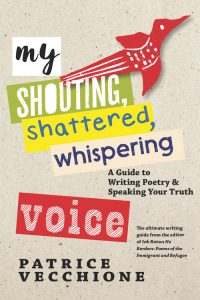

My Shouting, Shattered, Whispering Voice by Patrice Vecchione is available via Seven Stories Press.

Patrice Vecchione

Marcelo Hernandez Castillo called Patrice Vecchione’s new book, My Shouting, Shattered, Whispering Voice: A Guide to Writing Poetry & Speaking Your Truth (Seven Stories Press), “required reading for beginning writers as well as though who have been writing for decades.” And Ellen Bass called it “a helping hand to anyone who dreams of telling their truth through words on a page.” Patrice is the coeditor of last year’s Ink Knows No Borders: Poems of the Immigrant and Refugee Experience. More at patricevecchione.com.