The Hidden Power of the Passive Protagonist

Jessi Jezewska Stevens on Characters with Perpetual Potential

Here’s a dull joke (all jokes with semicolons are): a novelist spends her twenties not going out or talking to people very much; a few years later, she finds her sudden and primary responsibility to be going out and talking to people, specifically about the book she wrote.

The upside is that interviewers and readers are fortunately much better at querying what the novelist has written than she is, which turns talking about the book into a process of (re)discovery. One of the things I’ve rediscovered about my own book, though recent conversations, is that it revolves around a passive (or at least initially passive) character, and that this is a choice that comes with risks.

I’ve been reflecting on those risks. Passive protagonists can ruin things for any number of reasons. They resist and retard drama. They lack motivation. They’re weak. These are but a few of the warnings touted out against passivity in writing workshops. There’s perhaps a special danger in writing a passive woman, a trope that rests on centuries of male underestimation of the weaker sex. Each of these disclaimers has its merits, and one must proceed with caution. Even still, I feel motivated to make at least half an argument for the passive, lazy lead, who, despite the wisdom of popular craft, I also find uniquely useful for cutting through the bullshit of a very troubled world.

*

If there is precedent for the narrative utility of the acquiescent disposition, then its first and most famous exponent must be Voltaire’s optimist, Candide. “He combined a true judgement with a simplicity of spirit, which was the reason, I apprehend, of his being called Candide,” the novel begins. In other words, at first characterization, Candide is a little stupid, and that is exactly his charm. Too gullible for cynicism, too simple for ambition, he instigates almost none of the obstacles on his ill-fated, picaresque path. He is, in a sense, the anti-Virgil of the absurd.

Candide embodies the first virtue of the kind of passive protagonist I’d like to consider here: the reservation of judgement and a deference to fate. That Candide is able to maintain the conviction that he lives in the “best of all possible worlds” through a series of increasingly violent misfortunes is a feat that can only be achieved by forgoing reflection and protest; rather than rejecting the vengeful illogic of a world uniquely designed to screw him over, Candide exists in the moment. He is good-natured, genial, fundamentally optimistic and only ever accidentally wise—the kind of person who throws others’ intelligence and cynicism into relief. Here lie the Berty Woosters of the world, through whom we meet a Jeeves.

The caveat, of course, is that Candide—or Bertie Wooster, for that matter—is entertaining only insofar as his dimwittedness leads to plot-inducing, picaresque shenanigans. For this reason, by page three, Candide has already been evicted from “the best of all possible palaces,” the event that kicks off a series of mortal tragedies including torture, shipwreck, imprisonment, and worse. (One of the darkest jokes, really, is that Candide seems unable to die.) Once this quest begins, the protagonist is forced to make decisions, thereby becoming not so passive at all. Passive protagonists aren’t completely resistant to drama, then. It just takes a certain kind of exaggerated world to force them to respond.

I find some variation of this pattern in many of my favorite novels. In Amos Tutuola’s The Palm Wine Drinkard, an alcoholic wanders off into the Nigerian bush in the hope of resurrecting his top palm tree tapper. Karl, the engineering drop-out at the center of Kafka’s wonderfully ridiculous Amerika (which he wrote, famously, without ever having visited the States), glides through a series of increasingly roguish escapades after his parents banish him from Germany to New York. The list goes on: The unnamed, underemployed narrator of Anna Burns’s Milkman has no greater ambition than to go on long runs and read novels, and would happily do just that, if only she weren’t being stalked by a powerful Irish nationalist; the pregnant protagonist of Marie NDiaye’s Rosie Carpe is so psychologically and financially exhausted that she has no choice but to follow a stranger through a haunted Caribbean landscape and, later, deep into a family mystery. And where would Du Maurier’s Rebecca be without our insipid narrator, whose maddening passivity throws the posthumous power of the first Mrs. de Winter into relief?

Limpid agency can be a state of potential, the precursor to obsessive quests.

Perhaps the most potent counter-proof to those suspicious of the narrative potential of passivity is Bartleby, whose central conflict is defined by two of Anglophone literature’s most superlative wet noodles to date. Bartleby’s inertia (“I’d prefer not to”), combined with his employer’s spinelessness, becomes an unlikely and yet undeniable recipe for tragicomic drama.

All of these novels reveal a second advantage of the passive character: limpid agency can be a state of potential, the precursor to obsessive quests. (Bartleby takes this even further by making the lawyer’s a stationary quest, as he endeavors to evict the scrivener from the immediate vicinity his own office.) Rather than issuing passive narrators an endorsement carte blanche, we might say that we support them insofar as they exist to motivate a quest.

Conveniently, the quest is also one of the most fundamental forms of novelistic plot. So argued Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky in his foundational Theory of Prose. In the tale he offers as a prime example, the Russian legend of ‘The Rooster and the Hen,’ we recognize the hapless nature of our favorite archetype. In Shklovsky’s summary, a hen trades trades a pin for a rooster’s pea, whereupon the imbecile rooster promptly eats the pin and begins to choke. This prompts the hen to run to the sea to ask for water; the sea agrees on the condition that the hen first bring her a badger’s tusks; the badger agrees only if the hen procures an acorn; the oak tree agrees if only the hen will … et cetera, et cetera. The relationships between events in the hen’s quest are chosen less to preserve the logic of the plausible—of character motive or cause-and-effect—than to prevent the story from ending too soon, or in the wrong place, or on the wrong note. It is these delay tactics, Shklovksy argues, or “peripeteia,” that form the foundation of plot.

But there is another, implicit, and equally important ingredient here: the aimless, obliging nature of the central character of the hen. It is her naive disposition allows her to fall prey to the frivolous whim that instigates her quest, and, later, to be hoodwinked into the detours that prevent her from completing it too rapidly.

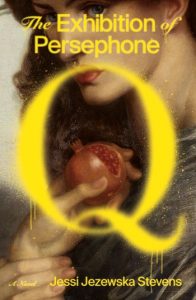

In my own novel, my narrator, Percy Q, is so in denial about the transitions in her life that she is poised to welcome any distraction from them, including a disturbing, mysterious exhibition catalog that arrives in the mail. The title is “The Exhibition of Persephone Q,” and Percy recognizes herself as the woman in the pictures it displays. The knowledge that she is featured in a gallery show—and her subsequent indignation, when no one else believes her claim that she is the woman in the pictures—becomes the perfect procrastination technique. What a relief! Neglecting her marriage and her impending motherhood, she throws her whole heart into convincing everyone she can that she is the real Persephone Q, only to wind up doubting her own ability to recognize herself. When I was writing the book, I felt it was her very lack of worldly ambition, her will for self-delusion, that made her suitable for such a plot.

Honestly, revisiting this summary, I’m still unsure whether Percy qualifies as passive in the way we’ve been discussing it or not. But I do think the quest-as-plot, combined with a slightly lazy lead, is appropriate for a moment when our suspension of disbelief for “peripeteia” is at an all-time low. The attentiveness of Silicon Valley to resolving the minor frictions of day-to-day, middle-class life has left it nearly, well, frictionless; Amazon Prime has done a number on character motive by reducing the need to ever leave the house. Consider this revision to a famous opening line: Mrs. Dalloway said she’d order the flowers herself. Substituting the original “buy” with “order” eliminates the need for plunging into London’s Streets, for meeting the people that Mrs. Dalloway does. It ruins the occasion for writing a novel at all.

I also think there’s a case to be made for the passive character as implausible hero of the American novel.

Obviously a contemporary protagonist might easily and believably head to the florist’s (although, would today’s readers believe as strongly in the motive of procuring those flowers for a dinner party….?) But it takes a certain kind of unfrazzled, unrushed character—by today’s standards, a slacker—to physically visit the florist in a world where there’s an app for that. Yet, even as the surfaces of life become ever sleeker and slicker, the feeling persists that everything beneath that surface is rotten. This leaves writers in a mild paradox. We need novels for rooting out that rottenness, even as raw material of narrative—our lives—becomes increasingly inimical to plot.

I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that, because of this tech-aided divergence between the surfaces and the souls of things, the current American condition is one of feeling perpetually gaslighted. Our government and corporations assure us we’re doing better than ever, even as intuition tells we almost certainly are not. This sets the stage for the kind of story in which an average American citizen would like nothing more than to mind her own business, except she can’t, due to the nagging feeling that something is terribly, terribly wrong. That premonition becomes an obsession, an illness, and, in a novel, the motivation for a quest: If only one could put this presentiment of disaster into words.

If feeling gaslighted is a viable diagnosis of our contemporary unease, then I also think there’s a case to be made for the passive character as implausible hero of the American novel, someone who can move through the world with Candide’s accidental wisdom while letting it damn itself. Enter the passive protagonist, the quest. Only someone with a great deal of free time can go chasing after windmills, after all.

This is hardly the only applicable model. By the time this essay runs, I suspect it will have already expired, the world moved on to something else. If I’m to write a second book, I might choose a different approach myself. In fact, I hope I would. But old habits die hard, and I’m not much one for self-improvement—probably I won’t.

__________________________________

The Exhibition of Persephone Q by Jessi Jezewska Stevens is available now via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Jessi Jezewska Stevens holds a BA in mathematics from Middlebury College and an MFA in fiction from Columbia University. Her stories and essays have appeared in The Paris Review, Tin House, Guernica, BOMB, and elsewhere. She lives in New York, where she teaches fiction. The Exhibition of Persephone Q is her debut novel.