“Piss and Pride”

It was almost the end of the ninth month in the Tibetan calendar, but it was still hot in the city, on top of which his fur jacket was a bit too thick, making him sweat profusely and feel an unbearable thirst. He really regretted that he hadn’t worn something lighter yesterday. When he thought about it, though, there wasn’t much he could have done, since when he’d left the house the previous morning it was raining and snowing, and a cold wind was blowing—not exactly “home sweet home.” Fortunately, he didn’t have to go too far before he came across a place selling tea and other drinks beneath a big multicolored parasol. He drank several cups of tea in succession, then continued to roam the shops looking for the radio his neighbors had asked him to get.

He had no idea how far he’d walked, but when he turned to look he could see the college building where his son went to school—the one decorated with the eight auspicious signs— standing out clearly among the other tall buildings like the moon amid the stars. This gave him some comfort, and he kept going.

After a while he felt the need to take a piss, and he remembered what his son had said to him: “If nature calls, you have to go to the public toilet. There are lots of them on the main roads. If you pee any old place, then getting a fine would be the least of our worries—you’d be harming the reputation of our nationality.” He looked around, but nowhere was there a building resembling this “public toilet” he had in mind, so he kept going.

He saw a few men go into a building, then emerge shortly after, doing up their trousers as they went. Could this be the public toilet? he wondered. But this building was even nicer than the dorms at his son’s university, and when he approached the doorway he was met by a drifting aroma of incense. No way, he thought, and decided not to go in.

By this point his bladder was on the verge of bursting. He stopped a passerby and said, “Arok, buddy, ah . . .” then made some gestures with his hands (he wasn’t a mute, but he didn’t know Chinese, so what else could he do?). “You’re the aluo, not me!” the man replied in Chinese and stormed off.

“Eh, I wish I knew some Chinese,” he mumbled to himself. He scanned the area until his gaze finally fell on the secluded corner he was after, but immediately he remembered “the reputation of our nationality” and forced himself to hold it in.

“Best if I just get back quick as possible,” he thought, turning around and picking up his pace. Soon he was half trotting half running, and then he broke into a full-blown sprint. This was the first time since he’d turned forty or fifty that he’d run like a kid, full tilt. Unfortunately, a sudden unbearable pressure doubled him up, and he was left clutching his crotch as he supported himself with each heavy step forward.

The building decorated with the eight auspicious signs seemed so close—how come he still hadn’t gotten there yet? Before his eyes all was grassland, where anywhere you turned there were countless places you could piss to your heart’s content, completely worry free. Oh what a wonderful thing it is, to take a carefree piss! The tall buildings in front of him began to wave back and forth. “Ah, I can’t hold it anymore!” He came to a halt, but then he thought of the previous evening when his son’s college friends were talking about how every time someone from their hometown came to the city they committed some “faux pas” or other, and he thought about the angry and pained expressions on each of their faces. I can see why the youngsters get mad. I mustn’t bring shame on the next generation, he thought, and like a wounded man filled with resentment he clenched his jaw, bit his lip, and continued to drive himself onward. Finally, he arrived at the main gate of the college building decorated with the eight auspicious signs. When he regained consciousness, he couldn’t remember what had happened after that point. In any case, he’d collapsed the second he walked into his son’s dorm.

When he woke up he was surrounded by his son and his son’s college friends. There was a piss stain on his crotch, and he looked up at his son, filled with embarrassment and remorse. “Your dad has brought shame on you,” he said. His son, his expression somewhere between tearful and delighted, replied, “Don’t worry, Dad. You didn’t harm our national pride in public—I couldn’t be more grateful.”

“The Story of the Moon”

“Grandpa, tell us a story!” the last group of children on earth—who didn’t wear even a scrap of bark, much less animal skin—begged the old man pitifully.

This world, where the mountains and plains were bereft of flowers and no water flowed in the riverbeds, was silent and sorrowful. The lives of the children, who had no lessons to go to and no games to play, were even more dull and barren. And so, all day long they surrounded the elders and pleaded for stories.

“Hmm, all right, all right.”

“Thank you, Grandpa! Thank you . . .” The overjoyed children clapped their little hands.

“Once upon a time, there was a princess who was as beautiful as the moon on the fifteenth . . .”

“Grandpa, what’s a moon?”

“The moon? Oh, well, a long time ago the moon was the closest heavenly body to our earth. Every thirty days it would rise in the sky at dusk, looking just like the curved eyebrow of a pretty girl. With each passing day it would grow rounder and clearer, and after about ten days it was all white and round—absolutely beautiful. For that reason, the ancients always compared a pretty girl to the moon.”

“Well, why isn’t it here anymore?”

The old man sighed. “Then let me tell you the story of the moon. In the time of my grandfather, we human beings had very advanced science and technology, and the achievements of these skills were many. But some scientists thought that the natural environment of the earth was bad, and the reason for global climate change was that the orbit of the earth was slightly askew. If, when the moon passed over Antarctica, they could blow it up with explosives, a large amount of lunar soil would fall into the Pacific Ocean, and then the orbit of the earth would be corrected.

“Back then, human beings had many nuclear weapons with the power to destroy the earth ten times over, and the moon was only a quarter the size of the earth, so needless to say they would have had no problem blowing it up.

“The scientists ignored people’s protests. With all their technology—spaceships, space stations, lasers, nuclear facilities, radio telescopes, supercomputers, robots—and with the help of all the brightest and best minds in science, they blew the beautiful moon to smithereens.

“Upon witnessing this fearsome spectacle, the peoples of other planets—whose science was very very advanced—thought, So badly have the terrestrials defiled the mother Earth on which they depend that living beings there can hardly breathe anymore, and now they’ve even stretched their claws into space and destroyed the most beautiful of the heavenly bodies in the solar system. How terrible! We can’t let them carry on like this, no matter what. And so they destroyed all civilization on earth. Not only was all of humankind cast back once more into a primitive state, but waves of natural disasters and epidemics on an even greater scale than in the past wiped out hundreds of millions of people, leaving us in the situation you see today.”

“Grandpa, you just made that up! It’s not a true story. Go back to the story of the princess.”

The children didn’t like the story of the moon because they’d never heard of things like “science and technology,”“nuclear weapons,” and “space stations,” and they had no idea what those words meant.

The old man had no choice but to tell them a story from the age of civilization, about a princess who died of a drug overdose and destroyed her whole family. . . .

__________________________________

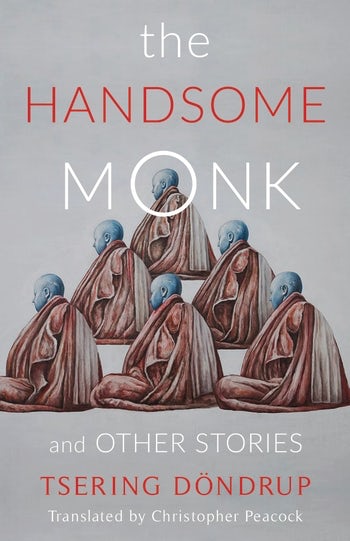

From The Handsome Monk and Other Stories. Used with permission of Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Tsering Döndrup, translation copyright 2019 by Christopher Peacock.