The Grief of Publishing a Book Without the Parent Who Inspired You

Monica Macansantos on the Words Her Father Awakened

For Francis C. Macansantos

A few years after moving back into my family’s ancestral home in the Philippines to mourn my father’s passing, I find myself rifling through a cupboard where his old notebooks are stored. In a moment of renewed grief, I’m hoping to be consoled by his messy, hurried penmanship in which he chased the words that would form his poems. In these musty-smelling pages, I discover drafts that never made it into his published books, including an old poem he wrote in 1989 in which he describes himself as a new father, fearing for the life of his two-year-old daughter as she dozes in his lap. As I read this poem that he wrote for me years ago, the silence he left me with upon his death becomes filled with his own sense of mortality that haunts and comforts me at once:

I fear for your life

As much as I have for mine

For a lifetime, my lifetime,

Up to this point of our breathing deeply,

Of watching you asleep so peacefully,

Of knowing that as you live on

You may take after me,

After a troubled heart

Yearning for consolation

As I have yearned for you.

Five years after his passing, I find solace in the way he reckons with his own fear of death as he contemplates my slumbering two-year-old self, marveling at the life he has created while being forced to confront our shared mortality. I come to his poetry for answers, and when he responds with his own anxieties, I feel less alone in my grief, knowing that the loss I now feel is exactly what he dreaded:

But my fears for you are deeper—

Like having to live in fear of death twice over.

I have no control over these losses, it seems that my father is saying to me in 2022. You will have to live with this fear I carry within me, long after you outlive me.

*

At 67 years old, my father had more years ahead of him, or so we thought: he had no health problems we were aware of, and still possessed a sharp mind that he used for formulating the witticisms he was famous for in the Philippine literary community, as well as the sharp observations that made his poetry so astonishing. At the time of his death in 2017, he had started working on a new collection of poems about people he knew during the Marcos dictatorship, who had since disappeared in time (or else had been “disappeared” by the dictatorship). Shortly after his funeral, I found the notebook where he wrote the titles of these poems he hoped to write at the top of each page. He never had the chance to fill the blank spaces that followed.

Now that these stories he read and admired will finally exist in a physical book, I find myself seeking his presence again.

As I came to terms with my own devastation following my father’s sudden passing, I consoled myself with the thought that the poems he had left behind allowed me to hear his voice again when I found myself seeking his presence, and that I felt connected to him when I sat at my desk to write. He lived in his own words, as he did in mine, and over the years I came to accept that in his absence, this too could be enough.

In the months leading up to the publication of my first book, a collection of stories I completed before his death but struggled to find a publisher for until recently, there have been nights when I’ve found sleep elusive. I hadn’t expected the impending publication of my first book to throw me off balance, to take away a delicate semblance of peace that my writing has given me in the years following his death. Oftentimes, I feel as though I am floating down a void, accompanied by no one and nothing, unable to ascertain if there’s anything out there that I can hold onto to prevent me from floating endlessly away. I am not sure what it is about releasing a first book that has triggered these moments of disorientation between wakefulness and sleep. The gift of language I received from my father, after all, was meant to sustain me even after his passing.

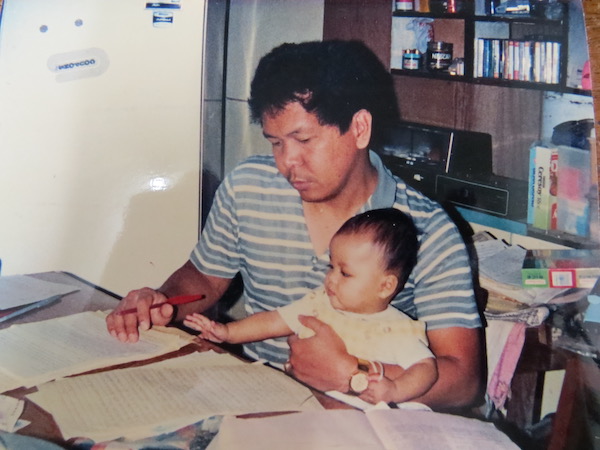

The author with her father. Photo courtesy of Monica Macansantos.

The author with her father. Photo courtesy of Monica Macansantos.

In my more anxious moments, I try to remind myself that I am fortunate to have found a home for this book, which I once thought would never see the light of day. Six years ago, when I signed with a NYC-based literary agent, I had an inkling of the challenges that lay ahead for us in placing this collection, though I never would have guessed that it would take this long for the book to find its way into the world.

A month after my agent started submitting my book to Big 5 publishers, I returned to the Philippines from New Zealand, where I was living at the time, to spend what was to be my final Christmas with my father. As he washed our dinner dishes one evening, I confided in him about my own anxieties over my agent’s ability to sell my first book. For my father’s generation of Filipino writers, signing with an American literary agent was unthinkable, and to be able to sell my book to a major publishing house would be to achieve a miracle that none of us who were born and raised in the Philippines were meant to pull off. I had defied the odds and found an agent who connected to my stories, but was I capable of performing the rest of this magic trick?

“Don’t underestimate the young,” my father said, when I expressed my misgivings about my agent’s youth. “The young can see what others fail to see. Just like you, with your own writing.” Unfamiliar with the commercial intricacies of the US publishing system, my father believed that a purity of vision was enough for my agent and I to get the publishing deal we wanted. He knew, of course, that there was no guarantee of a straightforward path for his daughter, but his faith in my work was enough to convince him that my first book would find its way into the world, in whatever form.

He would have rejoiced at the publication of this book, even if it’s happening in 2022, years after we had that conversation and years after I parted ways with that agent. I wish I could tell him that he was right; that his faith in these stories wasn’t misguided or naïve, even if the long and bumpy road I faced in finding a publisher, which entailed many rejections from Big 5 and small press editors alike, wasn’t what any of us foresaw. He had read all the stories in this collection when they were files on my computer, before they found homes in literary journals, and was often the first person to tell me what these stories had to say before even I could fully understand their meanings. As a Filipino poet working in English who had never enjoyed any form of commercial success and often struggled to find an appreciative audience in his own country, he never lost sight of what really mattered, which was to write well and to have something significant to say.

There’s a part of me that hopes that the magic and light my father awakened in my words will also be treated with care.

His belief in my work’s substance was what kept me going after his passing, whenever I was plagued by self-doubt and nagged by the thought that maybe these personal sacrifices I was making for my writing would be for naught, that I’d never publish a book and would thus fail to reaffirm his belief. Now that these stories he read and admired will finally exist in a physical book, I find myself seeking his presence again, not really knowing how these stories will fare once they reach a wider audience, wishing he was here to firmly ground me in his faith.

*

Writers often speak of the sense of loss they experience when bringing a book into the world—publication, to some degree, is an act of severance, made personal by its extraction from one’s very being, enabling it to survive on its own. Because of the time I’ve had to spend finding a publisher for this book, it now seems to me like a vessel from a time when my father was still around to read and respond to my stories. Would it matter to readers of my collection if they knew just how much my father belongs to the book they hold in their hands? Would they give any second thought to how my father gave me the space and creative freedom I needed to write these stories, without abandoning his role as mentor and guide? As a writer, I want readers to care about the stories and not their backstory—and yet there’s a part of me that hopes that the magic and light my father awakened in my words will also be treated with care.

Perhaps I am disregarding our capacity as writers to create work that connects readers with our own hopes and desires without having to be present in their lives as the mortal beings that we are. It’s a thought that comforts but frightens me, since it reminds me of my own mortality, of my own inability to retain control of the things I have created. Maybe I will have to accept that my more perceptive readers won’t see in my stories the loving father who continues to play a central role in my art, but rather some intangible force that animated my father’s life and work. This force is all I have left of him, and it still gives me reason to mourn.

Did my father understand why I grieve as he wrote these lines for his baby daughter?

My little immortality,

I have been small consolation

To my forebears as to you.

But we are each other’s great illusion,

Sharing love, our phantom bread.

__________________________________

Love & Other Rituals by Monica Macansantos is available via Grattan Street Press.

Monica Macansantos

Monica Macansantos is the author of the essay collection Returning to My Father’s Kitchen (Curbstone, 2025) and the story collection Love and Other Rituals (2022). She was recently a Shearing Fellow with the Black Mountain Institute in Las Vegas and is a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers. Her writing has recently appeared in River Styx, Bennington Review, and Poor Yorick.