The Greatest Velmas of History and Fiction

Shaenon K. Garrity Takes Roll Call, from Agatha Christie to Harriet the Spy

From What Would Velma Do? out now from Running Press.

Velma may be the modern model of a particular ideal, but it’s an ideal that’s existed since a nearsighted Australopithecus shone a torch into the back of her cave to logically prove that the Ghost Mammoth was just Ogg with a blanket over his head. Many women throughout history have embraced the principles of the VELMA System: writers, scientists, investigators, polymaths, and general know-it-alls. If real historical humans with their admitted flaws aren’t inspiring enough, you can find avatars in literature, film, and television. Here are just a few of the notable Velmas of history and fiction.

*

Émilie du Châtelet

(1706–1749)

“If I were king, I would redress an abuse which cuts back, as it were, one half of human kind. I would have women participate in all human rights, especially those of the mind.”

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, the Marquise of Châtelet, lived a Velma ideal of French decadence. Born into nobility and married into greater nobility, she spent most of her time at the du Châtelet country house, pursuing her favorite interests: science, math, and holding intellectual parties. One of her regular guests, the scandalous satirical writer Voltaire, became her live-in lover. On a typical day, they’d meet for breakfast and conversation, then retire to separate wings so he could write and she could do scientific research and translate Newton.

Admittedly, Émilie’s relationship with Voltaire was often rocky, and the good times were cut short by her death in childbirth at 42, a harsh reminder that even the rich-French-people past is a place that would be fun to visit but certainly not to live. But science and philosophy parties! With wigs! It’s one of history’s sweetest setups for a bookworm.

Life Lesson: Even if your personal life is on the chaotic side, it’s nice to have your own science castle.

Rosalind Franklin

(1920–1958)

“What’s the use of doing all this work if we don’t get some fun out of this?”

English chemist Rosalind Franklin is often called “the dark lady of DNA,” which sounds romantic but basically means she got cheated out of credit a lot. Smart and driven from an early age (noticing a pattern in these bios?), Rosalind was culturally Jewish but agnostic from early childhood, once asking her mother, “Well, anyhow, how do you know He isn’t She?” She graduated from a Cambridge women’s college with a degree in chemistry and became an expert in photochemistry, the then-new technique of photographing molecules to study their structure. She spent the 1940s studying the structure of coal and graphite, then turned to biological molecules.

In the early 1950s, Rosalind took X-ray diffraction photos of DNA molecules and noted that they appeared to be helical. The team of James Watson and Francis Crick, aided by one of her photos on top of their own research, confirmed that DNA forms a double helix. Watson did her dirty in his book The Double Helix, framing her as unimportant to DNA research and little more than an assistant; he and other scientists disliked her sharp attitude and sloppy dress. Rosalind shrugged it off and continued working until her sadly early death from cancer in 1958. In her personal life, Rosalind had little interest in romantic relationships. Seeing some of the things her male colleagues said about her, it’s understandable.

Life Lesson: If you stay true to yourself and make a difference, history will remember you, even if you didn’t always get the credit you deserved.

Zora Neale Hurston

(1891–1960)

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

A writer, anthropologist, journalist, folklorist, and firebrand, among other pursuits, Zora Neale Hurston was a renaissance woman of the Harlem Renaissance—but if you told her that, she’d probably bristle at being lumped into any group. Brilliant, opinionated, and unapologetic, she was deeply influenced by her childhood in an all-Black farm town in Florida founded by formerly enslaved people. She studied at a series of prestigious universities—Howard, Barnard, and Columbia—and wound up in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in the 1920s, hanging out with other ambitious young Black intellectuals. Her rural upbringing and often conservative politics put her at odds with the city-bred liberals who made up most of her social circle, and she never passed up an opportunity to speak her mind about it. She hosted lively intellectual parties at her apartment, sometimes slipping to her bedroom to write while the party continued outside.

During her unbelievably busy career, Zora cofounded the literary magazine Fire!!, reported for magazines and newspapers, wrote plays and fiction including the classic novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, and traveled the world researching anthropological subjects from Southern folklore to Caribbean voodoo. She had trouble making money, and she died in obscurity and poverty; only after her death was her work rediscovered for critical appreciation. Would she have done anything differently? Oh heck no.

Life Lesson: The world may punish you for sticking to your guns, but what are you going to do, be wrong?

Frances Glessner Lee

(1878–1962)

“Look here, young man, you’re trying to anticipate what I’m going to say and you haven’t brains enough to do it.”

Okay, this one’s kind of obscure, but hear me out. The daughter of a wealthy Chicago industrialist, Frances Glessner Lee lived the life of a debutante and married a lawyer. But her family discouraged her supreme passion, forensic investigation, which she taught herself by studying the research of the day and following cases. Starting in the 1930s, she used her fortune to establish a medical examiner program at Harvard and taught week-long seminars on detective work.

As visual aids for her seminars, Frances built miniature dollhouse-style dioramas of sample death scenes. Her “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” included such tiny details as stockings she hand knit with tiny needles, cigarettes hand rolled with real tobacco, glass made to spec by an interior design firm, a coffeepot with actual coffee grounds in the strainer, and doll corpses painted to suggest clues to the cause of death. The cases in the Nutshell Studies aren’t designed to be solved, but to present examiners with opportunities to find and analyze clues.

In return for her work, Frances became the first female police captain in the US and is known today as the “godmother of crime scene investigation.” The Nutshell Studies are still used in homicide investigation training. Maybe best of all, she was embraced by the crime-solving world she loved: medical examiners credited her with legitimizing the field, she made friends with mystery writer Erle Stanley Gardner (the guy who created Perry Mason), and police detectives sent her cards on Mother’s Day.

Life Lesson: Do your weird thing and your people will find you.

Agatha Christie

(1890–1976)

“The truth, however ugly in itself, is always curious and beautiful to seekers after it.”

All girl detectives owe at least a little something to the Queen of Crime herself. A voracious reader from an upper-middle-class English family, Agatha Christie started writing mystery novels while serving as a nurse during WWI; working at a pharmaceutical dispensary gave her a handy knowledge of poisons. Her detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple (also Tommy and Tuppence, but everyone forgets about Tommy and Tuppence) soon became beloved characters, and the annual publication of a new “Christie for Christmas” grew into a British tradition. Agatha was the center of a mystery herself when, during the breakdown of her marriage to her unfaithful first husband Archie, she disappeared for almost two weeks, only to turn up at a hotel claiming to have no memory of how she got there. She later married Max Mallowan, an archeologist, and spent the latter half of her life traveling the world with him and writing bestselling novels at his exotic dig sites, an incredible lifestyle goal.

Agatha had that Velmic competitive streak: she supposedly started writing mysteries to win a bet with her sister Madge, who had been considered the gifted one when they were growing up. You don’t become the bestselling novelist of all time and the author of the longest-running play of all time (The Mousetrap, at London’s West End since 1952) without some serious head-of-the-class drive.

Life Lesson: Everyone loves a good mystery. Also, it’s totally reasonable to hold out for an actual, real-life Indiana Jones. (That said, I must report that Max Mallowan did not look like Harrison Ford. In fact, he looked a little like Hercule Poirot.)

Katherine Johnson

(1918–2020)

“If you want to know you ask a question. There’s no such thing as a dumb question, it’s dumb if you don’t ask it.”

As you may already know from the book Hidden Figures, or the movie Hidden Figures, or the Hidden Figures Lego tableau you designed yourself to keep on your desk for inspiration, Katherine Johnson was excellent. One of the human computers whose calculations helped launch John Glenn into orbit, Katherine set her sights high from the start. She attended high school at age 13, graduated with highest honors from the historically Black West Virginia State College, and was selected as one of the first three students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools. In 1953, she went to work as a computer at what was then the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which had an all-Black computing section.

When NACA became NASA, Katherine went along with it. Being the most trusted computer on the team behind the first American manned space flight was just the beginning. Later, she worked on calculations for the Apollo moon launch and the Space Shuttle. Of her 33 years at NASA, she said, “I loved going to work every day.” That’s even more satisfying than being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which she also did.

Life Lesson: You don’t have to find total job satisfaction to be happy… but wow, does it help.

Dana Scully

As seen in: The X-Files

“The truth is out there, but so are lies.”

She looks like Daphne, but Agent Dana Scully is so completely a Velma. A crack FBI agent with a medical degree and a scientific mind, Scully winds up partnered with Fox “Spooky” Mulder on the X-Files, unsolved cases involving the inexplicable and possibly paranormal. Her job is to be the rational yang to Mulder’s so-open-minded-his-brains-fall-out yin, but since unlike the Scooby gang, Mulder and Scully encounter phenomena that can’t be explained as a crook in a rubber mask, her skepticism is constantly tested. After getting abducted by aliens, even Scully has to admit, at least once in a while, that there are things conventional science can’t explain.

Scully has more trouble with the mysteries of human relationships, dancing for season after season around the possibility of starting something with her brooding and comely partner. Thanks to various sci-fi shenanigans, she and Mulder manage to have a son together before they get past second base. Deep down, Agent Scully is still the awkward teenage redhead whose prom date was interrupted by a fire and had to ride home in the pumper truck.

Life Lesson: The VELMA System combination of Very Smart and Acerbity is so powerful it can withstand even David Duchovny’s doe eyes.

Harriet Vane

As seen in: the Lord Peter Wimsey novels by Dorothy L. Sayers

“I know what you’re thinking—that anybody with proper sensitive feeling would rather scrub floors for a living. But I should scrub floors very badly, and I write detective stories rather well.”

There are a lot of smart women in detective fiction, but Harriet Vane, created by Dorothy L. Sayers, is proudly brainy even when she isn’t solving mysteries. In real life, Sayers was one of the first women to receive a degree from Oxford, and Harriet is also an Oxford woman, graduating from a fictionalized version of the Oxford women’s college her author attended. Harriet is a successful mystery writer (think the character might be a tiny bit autobiographical?) but regularly has second thoughts about her decision to pen bestsellers and get tangled up in tabloid fodder instead of pursuing the pure life of the mind. She first meets the aristocratic detective Lord Peter Wimsey while on trial for the murder of her boyfriend, and, after clearing her reasonably good name, she teams up with him to solve more crimes.

In Sayers’s most famous novel, Gaudy Night, Harriet returns to Oxford to investigate a poison-pen mystery but spends more time debating philosophy, literature, and the future of women’s education. After turning down Lord Wimsey’s marriage proposals on a monthly basis, Harriet finally allows herself to hope that a relationship of equals is possible for women who are “cursed with both hearts and brains.”

Life Lesson: Of course it’s possible. Come on, Harriet.

Harriet the Spy

As seen in: Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

“I want to know everything, everything. Everything in the world, everything, everything. I will be a spy and know everything.”

Another great investigative Harriet! Eleven-year-old Harriet M. Welsch wants to be a spy when she grows up, so she skulks around a surprisingly kid-safe 1960s New York City listening at back doors, peering through skylights, climbing into dumbwaiters, and writing down everything she witnesses. For her daily spy route, she dons a very Velma ensemble of hoodie, well-worn jeans, and glassless horn-rim frames. Harriet loves making up stories and hates “girly” things; she only agrees to take dance lessons after her nanny, Ole Golly, tells her about the spy Mata Hari. (Yes, nanny—Harriet’s a rich kid with an Upper East Side apartment and absentee socialite parents.) She’s living her best life until her spy notebook falls into the wrong hands and she learns, as Velmas so often must, that not everyone can handle the unvarnished truth and that friends are even more important than data.

Life Lesson: If you can’t be a spy or a detective, maybe consider being a writer.

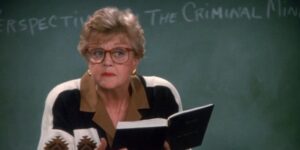

Jessica Fletcher

As seen in: Murder, She Wrote

“I am a writer. Crime is my beat. Murder my specialty.”

The pretty seaside town of Cabot Cove, Maine, somehow has one of the highest murder rates in the country. Fortunately, it’s the home of bestselling mystery writer Jessica Fletcher, who uses her no-nonsense attitude and extensive knowledge of crime to expose the tiny town’s apparently endless parade of wrongdoers. Far from a glamorous crimefighter, Jessica is a widow with sensible shoes and a brood of younger relations, especially her nephew Grady, who rely on her deduction skills. Before hitting it big as a writer, she was a schoolteacher, and after becoming famous as a detective she teaches writing and criminology at the college level. She’s even been elected to Congress!

Through it all, Jessica remains a down-to-earth woman who relies on brains and common sense, is secretly pleased when people think her life is more scandalous than it is, and, even after exposing hundreds of criminals, always hopes that this time people will do the right thing. A model of elder Velmatude.

Life Lesson: The VELMA System qualities of Mystery and Looking and Learning will serve you well through your entire life.

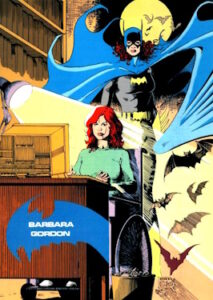

Barbara Gordon

As seen in: DC Comics, originally written by Gardner Fox and drawn by Carmine Infantino

“When it comes to research… never bet against a former librarian.”

There’s no way a crime-fighting, mystery-solving librarian isn’t a Velma. Babs, the daughter of Gotham City’s police commissioner, grew up wanting to be like her dad and stop criminals but becomes even more inspired when Batman shows up in town. What could a justice-obsessed overachiever do but make herself a costume, get a sick motorcycle, and start patrolling the streets as Batgirl? It takes a little effort to convince Batman and Robin that she’s more than just a fangirl, but soon Batgirl is an indispensable member of the Bat-Family. By day, she works at the Gotham City Public Library, which provides her with all the resources she needs for detective work.

After a run-in with The Joker leaves her paraplegic (at least for a while), Barbara adopts a new secret identity, Oracle, and applies her tech and information-gathering skills to lead an all-women crimefighting team called the Birds of Prey. Nowadays, she uses both her Batgirl and Oracle identities, not to mention her library science degree, to protect her city.

Life Lesson: Get a library card.

____________________________

Excerpted from What Would Velma Do? Copyright © 2023 by Shaenon K. Garrity. Used with permission of the publisher, Running Press. All rights reserved.