The Great White North Isn't So White

Towards a National Literature That Reflects the Make-Up of the Nation

Growing up in the 1980s and 90s in the suburbs outside Toronto, I was an immigrant kid who felt entirely at home in my physical surroundings. Toronto, even then, was incredibly multicultural and the burgeoning suburbs reflected that diversity. I went to schools filled with other immigrant and first generation students. Almost everyone’s parents had accents (British, Polish, Croatian, Indian, Chinese).

But most of us never saw ourselves reflected in the books we read. Characters were nearly always straight, white, and never questioned the gender they were labeled at birth. Immigrant narratives almost exclusively featured families from Italy or Ireland. Indigenous fiction was limited to the alt-facts we were taught in history class—and, yes, I’m calling what we read back then fiction, because the cartoonish antagonists of those textbooks bore no resemblance to the truth.

Today, Canadian literature is much more inclusive and our authors and their stories a better reflection of the population, its concerns and curiosities; not with a naval-gazing insularity, but with one eye trained on the wider world. As a result, our books are making a bigger splash at home and abroad.

In addition to the old triumvirate of Atwood, Munro, and Ondaatje—Margaret, Alice, and Michael having transcended the need for first names long ago—you might read Emily St. John Mandel, whose Station Eleven was an international blockbuster, Omar El Akkad’s critically acclaimed debut American War, or the work of national treasure Esi Edugyan whose latest, a Bildungsroman called Washington Black, was still hot off the presses when it landed on the Booker short list this fall.

What is most exciting about Canadian literature in this moment: the diversity of our stories and the plurality of the voices telling them.

What is most exciting about Canadian literature in this moment, though, is not the accolades, but the diversity of our stories and the plurality of the voices telling them. Today’s immigration narratives encompass a wider world and are sometimes constructed to subvert, calling into question who exactly is the immigrant. Gay characters aren’t always grappling with their sexuality, though of course that happens from time to time. Sometimes they are sparring with family or struggling in school.

We are writing coming-of-age tales set in the suburbs or at sleep-away camp, penning historical dramas, speculative fictions, fabulist tales that weave the fantastic with the everyday, and illustrated how-to guides featuring casts of characters who just happen to be diverse. We’re exploring climate change and depression and polyamory and sometimes the skin color, gender, and sexuality of the author bears no relation to those of their characters. Often, a character’s ethnicity is as parenthetical as height and hair color because of course the big things—birth, death, love—are universal.

In no particular order, here are some books that represent the current face of Canadian literature. Most are rising stars but a couple are old favorites.

Thea Lim, An Ocean of Minutes

Thea Lim, An Ocean of Minutes

(Simon & Schuster)

It’s the early 1980s and a pandemic has struck. When Frank gets infected, his girlfriend Polly pays for his treatment by taking a job with a time travel corporation that sends her to work 12 years in the future.

Polly arrives in the 1990s to find a divided America. In the poverty-stricken South, a time-travelling underclass work as indentured servants while the North, thriving and wealthy, bars entry to foreigners.

Lim takes the lovers-separated-by-time narrative further than any other writer I’ve read, exploring class divisions, migrant workers, racism, climate change, and corporate psychopathy. A searing indictment of so much of what presently ails us, Lim’s is a story for our time.

Zoey Leigh Peterson, Next Year, For Sure

Zoey Leigh Peterson, Next Year, For Sure

(Simon & Schuster)

After nearly a decade together, Kathryn and Chris have the kind of relationship that seems inviolable. They speak in a cutesy shorthand, have the books in their apartment arranged just so, and finish each other’s sentences. Enter Emily: a free spirit who eschews everything conventional. She lives in a commune, does odd jobs, and doesn’t care for monogamy. Chris is smitten and Kathryn might be a little bit too. Billed as a novel about polyamory, this book is really about relationships: platonic, romantic and the subtle shades in between.

Shyam Selvadurai, Funny Boy

Shyam Selvadurai, Funny Boy

(Harcourt Brace)

This linked short story collection follows Arjie, the titular “funny boy,” as he grows from being a child who likes to play the “bride” in a dress-up game with his cousins to a thoughtful teenager who explores his sexuality with a charismatic schoolmate. The book is set in Sri Lanka’s capital of Colombo against a backdrop of political unrest. As Arjie comes of age, so does the country, moving toward war.

Shyam Selvadurai, Cinnamon Gardens

Shyam Selvadurai, Cinnamon Gardens

(Harcourt Brace)

Set in 1920s Sri Lanka in the closing decades of colonial rule, Cinnamon Gardens follows Annalukshmi, a spirited young woman torn between her family’s pressure to marry and her own desire for independence, and her uncle Balendran whose facade of urbane family man is upended by the arrival of an old lover named Richard.

Sarah Faber, All is Beauty Now

Sarah Faber, All is Beauty Now

(Little, Brown and Company)

The best books are both immersive and educational. In Sarah Faber’s All is Beauty Now, I learned about the Confederados—Confederate refugees who fled to Brazil, where slavery was still legal—after losing the Civil War.

Fast forward to 1962 and a wealthy enclave of Rio, where a group of their descendants live in high style. At the center of this privileged community are Dora and Hugo, a golden couple who seem to have it all. But behind closed doors, Hugo’s mental health is failing and both Dora and their eldest daughter, 20-year-old Luiza, are keeping dark secrets. One day, while swimming in the ocean, Luiza disappears. Presuming her dead, the family makes plans to move to Canada where Hugo can access free health care. But Dora can’t shake the feeling her daughter is alive. As she goes on a search through the city, the reader wonders: has Luiza run away, been kidnapped, or is her mother following a ghost?

Gurjinder Basran, Someone You Love Is Gone

Gurjinder Basran, Someone You Love Is Gone

(HarperCollins)

Simran is at odds with just about everyone in her life. Her husband’s benign doting chafes. Her only daughter, away at university, is distant. She resents her brother for being her mother’s favorite—and her mother has just died, but her ghost appears to heckle Simran from time to time. Or is Simran’s guilty conscience playing tricks?

Moving back and forth between Simran’s story and her mother’s girlhood in India, where she falls in love with one man but marries his brother, this novel is a poetic exploration of grief.

Kim Fu, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore

Kim Fu, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

When an overnight kayaking trip to a remote island goes awry, a group of girls (aged nine to 11) endure an ordeal, the results of which reverberate through the rest of their lives. Told through multiple points of view, the novel follows take-charge, anti-social Nita, working class Andee, quiet orphan Isabel, stubborn, beautiful Dina, and aspiring girl detective Siobhan into adulthood. The narrative flips back and forth between the long arc of each girl’s life story and their shared misadventure on the island. I read this book hungry to learn what happened on the island but in the end it was the characters who were most beguiling.

Carrianne Leung, That Time I Loved You

Carrianne Leung, That Time I Loved You

(Liveright)

“1979: This was the year the parents in my community began killing themselves.” So begins Leung’s book about a multi-ethnic group of neighbors co-existing in a newly built subdivision. There’s the young couple trying to get pregnant, the woman whose demons speak to her from the flowers in her garden, the artistic boy bullied by a bigoted teacher, the kleptomaniac who reeks silent havoc in their midst, and best friends June and Josie whose secrets pull them apart just at the time in life when they need each other most. This novel-in-short-stories is deceptively slim, balancing heavier themes of suicide, racism, and sexual harassment with lighter imagery of iconic basement parties and tote bags stuffed with G.I. Joes. I devoured this book in a single, ecstatic, nostalgic gulp.

David Chariandy, Brother

David Chariandy, Brother

(Bloomsbury)

Michael and Francis are sons of a single mother from Trinidad whose main love language, familiar to immigrant children everywhere, is food. There isn’t a lot of money, and mom works constantly, but the boys are happy, growing up in a working-class high-rise peopled with residents from all over the world. But as young boys in a heavily policed neighborhood, their innocence is quickly lost. In the present day, adult Michael narrates the story of a brother whose absence is conspicuous. Francis is gone—but where, and why, are the central mysteries at the heart of this slow-burning novel.

Zoe Whittall, The Best Kind of People

Zoe Whittall, The Best Kind of People

(Random House)

When George Woodbury, a beloved science teacher, is accused of sexual assault by a group of students, his wife and children don’t know what to believe. Guilt haunts the novel like a specter and while Whittall toggles the point of view between daughter Sadie, wife Joan, and other family and friends, she cleverly keeps us out of George’s head. This is the kind of dark and thoughtful book that forces readers to reckon with their own biases.

Arif Anwar, The Storm

Arif Anwar, The Storm

(Simon & Schuster)

Sharyar’s visa is about to expire and soon he’ll have to return to Bangaldesh, leaving his nine-year-old daughter behind in the US. As time runs out and Sharyar scrambles to find a way to stay, the story of his heritage is revealed through a series of seemingly unrelated narratives.

In a tiny fishing village on the Bay of Bengal, a fisherman and his wife brace for a cyclone, the likes of which they have never seen. On the eve of Partition, a wealthy Muslim businessman is kidnapped by a Hindu gang. During World War II, a female British doctor in a garrison hospital in Chittagong forms an unlikely bond with a prisoner of war. And during a rare day off, two Japanese fighter pilots visit an ancient temple complex in the heart of Burma.

Paced to mimic the titular storm, the 1970 Bhola Cyclone that killed half a million people overnight, Anwar weaves the threads of each disparate story into a single startling picture.

Cherie Dimaline, The Marrow Thieves

Cherie Dimaline, The Marrow Thieves

(DCB)

A pandemic has robbed nearly everyone of their ability to dream. Indigenous people, the only dreamers left, are being hunted for their bone marrow, where dreams are said to reside. The book follows a young boy called Frenchie and the makeshift family he acquires after losing his own to the hunters. Together, this lively and loving group run north, doing their best to evade death by human hands even as the earth—ravaged by climate change—expires all around them.

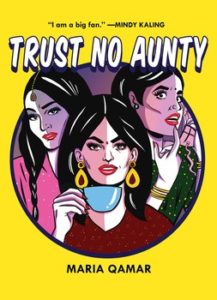

Maria Qamar, Trust No Aunty

Maria Qamar, Trust No Aunty

(Simon & Schuster)

Pop artist Maria Qamar’s book defies categorization. Graphic memoir, irreverent coffee table book, and illustrated survival guide for Desi girls, Trust No Aunty is unquestionably hilarious, full of bold imagery and brash tell-it-like-it-is hilarity. One page is devoted to everyone’s favorite accessory, the bindi, and includes a helpful chart that delineates when its use is appropriate (at an Indian wedding) and when it’s appropriation (at Coachella).

Lawrence Hill, Someone Knows My Name

Lawrence Hill, Someone Knows My Name

(W. W. Norton & Company)

Someone Knows My Name follows the indomitable Aminata from a bucolic childhood in Niger to her kidnapping and slavery in South Carolina, then to false freedom in Canada and a tenuous new start in Sierra Leon, culminating in an audience with the British monarchs.

This is a heartbreaking book with so much violence is done to a character you love from page one—but Hill never allows Aminata to accept victimhood. “I seem to have trouble dying,” she writes, showing us from the beginning that this tough broad is the author of her own life story.

Sharon Bala

Sharon Bala's bestselling debut novel, The Boat People, was a finalist for Canada Reads 2018 and the 2018 Amazon Canada First Novel Award. Published in January 2018, it is available worldwide with forthcoming translations in French, Arabic, and Turkish. A three-time recipient of Newfoundland and Labrador's Arts and Letters award, she has stories published in Hazlitt, Grain, Maisonneuve, The Dalhousie Review, Riddle Fence, Room, Prism international, The New Quarterly, and in an anthology called Racket: New Writing From Newfoundland (Breakwater Books, Fall 2015).