Welcome to West Florida, population my family and me and about a million and a half other people, more or less.

I guess we’re what you’d call the first family of the state, the Woolsacks, unless you call us criminals or enemies or crazy-ass coast trash on a spree. The Governor says that here we’re free to be our true bad selves, and that’s what West Florida means to her. Then again, Leona O., who owns my heart forever, says I’m all the state she’ll ever need, says I’m enough to fight for, wherever we are.

That’s the thing about West Florida: you might say it’s the ten counties and a little under two hundred miles of crystal sand and marsh and pineland that stretch from the Rio Perdido to Apalachicola, or you could say it’s just a dream. You could say it’s everything from the Mississippi north of New Orleans and on under the thirty-first parallel to down around the Big Bend, or you could say if there ever was a real West Florida it’s long dead now. You could call it a bastion of liberty, the last free place, like Troy Yarbrough’s people do, when what they really mean is a Jesus-riddled white ethnostate with a beachside pastel tinge. You could say it’s the unending glory of an awesome summer in which all our people have the right to be who and what they are, like the Governor says. You could say anything, including you’ve never heard of it till now.

Nothing wrong with that.

Me, I’m at the heart of this whole thing and I was almost thirteen years old before I heard of West Florida, and I’d been living here my whole entire life.

If you’d asked me back then, I would’ve said I lived in the Beau Rivage subdivision in Mandeville, Louisiana, with my Aunt Amber, until she died, and her husband Big Mike and their twin boys, Dakota James and Dakota Blake, named for the state where Big Mike made his money in the Bakken boom, before he and Amber got into the payday loan business. And if you’d asked them, they would’ve said I was the Murderbaby.

My mom, Nessa Pace, was Amber’s sister, and so she’d taken me in after I was found as a six-month infant heat-stroking in the back seat of a car parked behind the house where the quote-unquote Gulf Breeze Massacre had taken place. My mom’s car, to be exact. By the time Amber had collected me and brought me to live with them, Big Mike and his boys had already saddled me with the name.

Amber and Big Mike didn’t believe in keeping things from kids, no matter how little you were. They took great pride in telling it how it was, admired those who claimed to do the same, wore shirts explaining in list form their lack of filter, fucks given, and other traits. And according to them, when it came to me, the way it was, was this: My mom and Amber had grown up in Pensacola, even though their roots were here, in Louisiana, which Amber’d had the good sense to go back to as soon as she could, and she’d been genuinely happy for her little sister when she heard that Nessa was all eaten up with this boy named Kenan Woolsack, whose family, wouldn’t you know it, also had roots in Louisiana. Only their roots were all gnarled up and contaminated from leach water and probably ran through gas lines, and even though they had money his family were themselves the kind of reckless fuckheads who’d dig in their yard without calling the utility company and blow up a neighbor’s house or two on accident. A family of single moms and future single moms and boys who’d turn perfectly good girls into single moms.

Which is exactly what happened to my mom, according to Amber and Big Mike, and when it did, this kid Kenan not only dumped her, not only denied everything for months, but he wouldn’t even face her when she showed up, bump and all, at their door. Instead, his mom, Krista, and her stepdaughter, Alexis, and her daughter, Destiny, all got in my now-single mom’s face and said if they ever caught her on their property again they’d, well, do some criminal-ass shit. Had the nerve, when Nessa didn’t budge, to start in about the boy Kenan being too young for her, how she’d taken advantage of him. Which Amber always said was a bullshit excuse, and I guessed it was, but later when I did the math I saw he would’ve been heading into ninth grade that year and she a junior in high school. Regardless, my mom dropped out and had me, and Kenan would never make it to sophomore year. My mom ended up in Louisiana, where Amber and Big Mike could keep tabs on her, help her with bills and baby stuff, but she grew desperate and also addicted to drugs: Big Mike called it the despair that was killing white people, a phrase he’d heard some pundit say, which he went on repeating and applying to subsequent tragic deaths, including that of poor Aunt Amber, who went down as a result of fent.

The massacre happened because Nessa, my mom, kept scrolling through Facebook or Instagram and seeing these posts of Krista and Alexis, the ones who’d threatened her, denied her child, talking about how blessed they were and looking like the queens of summer. She shouldn’t have been doing it, Amber said, but my mom wouldn’t quit stalking the Woolsack women online and the Woolsack women wouldn’t stop posting themselves sunning beside their pool or leaning against new cars, and my mom, she started screenshotting the posts and sharing them, talking about how bad they’d treated her, and then one of those things happened: the kind that get people fucked up and believing in fate.

One of Nessa’s posts got shared outside her circle, liked for its fury against bitches who cover for their punk-ass sons, bitches who don’t deserve what they got and if there’s any justice in this world should get what they deserve, and the post was liked and shared until it ended up in the hands of one Tara Woolsack, whose half sister Alexis had left her to do six years in Elayn Hunt Correctional for attempted-murdering this guy they were going to rob back in the day. Six years while Alexis walked free and went off to live with her dad’s third wife on the motherfucking beach.

DMs were sent. Meetings held. Meth smoked. Weaponry arranged. A pistol-grip pump shotgun and a pair of Glock 15s with auto switches and a set of metal knuckles with these long, sharp Wolverine claws that Tara kept behind the counter at the vape shop where she worked. At first it was just something to make themselves feel better, Nessa and Tara and Blake, the guy Tara had attempted to murder and who she’d later married because life and love are strange, talking big about what they’d do, and then it became a plan and the plan was to get in there and steal some shit, including cash and a big old sheaf of bonds Pawpaw had supposedly stashed before he went inside. That’s what Nessa told Amber, before she left. They weren’t going in there trying to kill anybody. Maybe terrorize the shit out of them, she said, but not kill.

She’d confessed the whole thing to Amber in a single raging burst one night when I was six months old and wouldn’t sleep for nothing. Gave her a whole speech with me squalling in her arms. Amber told me later she tried to get her little sister to at least leave me there with her, where I’d be safe. Said when she asked my mom to do that, Nessa had glared at her with all the hatred in the world. Safe? she said, getting right up in Amber’s face. You saying my baby isn’t safe with me? Like I’m what? Dangerous? Well I’m a great fucking mom because I’m dangerous. Nothing’s ever getting between me and my baby, understand me? And pretty soon, me and him, we’re gonna get everything we’re owed.

Amber didn’t say anything back. Just watched her sister go.

By dawn Nessa had me in my little totable car seat on the road trip to the massacre.

I don’t know what she was thinking, what kind of future she envisioned. Maybe she saw herself as some baby cart assassin, thought that I’d grow up admiring her vengeance, or maybe she thought she’d take my dad as a gunpoint bridegroom, and reveal it all to me years later when we were celebrating their umpteenth anniversary.

I don’t know, but there I was: a baby riding along with a carload of maniacs slamming down the interstate to Gulf Breeze, Tiger Cove, where my mom and her accomplices would try to settle their scores, only to end up getting notched themselves.

Not to say they didn’t do some damage first.

On the morning after the massacre, the responding officers discovered Rodney, the surviving boy, locked in the master bathroom, to which he’d made his escape after being taken to the master bedroom, assaulted, and stabbed a number of times. To get there, the officers first had to follow a trail of gore through the house, accounting for the two women residents, Krista Woolsack and Alexis Woolsack, the body of Kenan Woolsack in the laundry room with his head in Nessa’s lap, she dead by gunshot wounds to the chest, and the attackers scattered throughout in attitudes of struggle, a fight amongst themselves perhaps, a freakout that left my mom and the other perpetrators dead.

Back when I was still ashamed of her, I liked to think that’s how it went. Like my mom had been killed by one of her accomplices, shot maybe because in the midst of whatever awful shit was happening she found herself filled suddenly with regret and tried to take it back, like when you’re little and you hit somebody and they start crying and all your rage dries up and you want to stuff all their tears back in their eyes, even though of course you can’t.

That’s not how it happened, though. I wouldn’t learn the whole truth until later, the details Amber and Big Mike didn’t know or the Dakotas couldn’t cook up or I myself couldn’t find in the articles I read once I had enough sense to google it or in the true crime forum threads I checked on for a while, where people geeked out over the whole thing.

Like I said, I had a lot to learn. And a lot to unlearn, too. Back then all anybody knew was that the girl, Destiny, was a missing person, status unknown. They found her Toyota in the driveway and her keys hanging from the flamingo wall-hook. The only clue she’d left was a trail of bloody footprints leading out of the house and down the driveway, articles of clothing strung in the reeds of the vacant lot across the street that ended at the shoreline, like she’d walked out of that Armageddon house and disappeared into the dawn-lit waters of the Santa Rosa Sound.

The people on the true crime forums posted theories and updates and unconfirmed sightings of Destiny for years. You had your she-was-in-on-it people and your ones who thought she survived and was wild and free and wandering the woods like Jeremiah fucking Johnson, who some say is dead and some say never will be, and others who said she died and got tossed into the water and was devoured by sea life. Mostly what seemed to hold their attention was the idea that she’d been in on it and double-crossed and trafficked into sexual slavery by heretofore unknown accomplices who’d somehow escaped detection by the forensics team. You could tell by the posts this was the version their hearts beat hardest for, the version where they knew more and better than the people who’d picked through the gore and numbered the entry wounds and shell casings, the version with an eternal victim in permanent pain.

I never bought that, me.

For most of my life, Destiny was a ghost, a nightmare, something to fear.

When I was little, the Dakotas would say she was coming for me. They’d say she was crab-crawling through the halls of our house at night so I stayed glued to my bed. Say if it was storming and I dared to part the blinds, she’d be standing there pressed up against the wet window, peering in, a vengeful spirit with no one left to take it out on, no one left to kill, except a murderbaby like me.

Didn’t matter to her that it wasn’t my fault or that I was barely alive when it happened. Probably the only reason she’d spared me that night when I was a baby, walked right past the car where I sat with the windows rolled up, crying in the heat, was because she was saving me for last, waiting until I’d grown and sinned enough to earn whatever hell she had in store for me.

The weird thing is, out of everybody’s theories, theirs was closest to the truth.

Even still, I never should’ve believed the Dakotas, considering these were the same brothers who’d once talked me into placing my fat little toddler hand on the overheated engine of their go-kart so that when Amber finally came out and took me by the shoulder and yanked me away, my palm came off like pizza cheese. But I believed them. I mean, I’d be lying if I didn’t say there were times when the Dakotas felt like brothers to me, times I held onto hard the fewer and farther between they got to be. And I’d be lying if I didn’t say I held out hope that they’d one day remember those times too, and take me under their Realtree-decked wings, but that was back when Amber was alive. When she died of the despair, her sons turned meaner than before. Not that I blame them much. They’re the ones who found her on the bathroom floor.

If I miss any of them, I miss Aunt Amber.

She was the only one I’d eat with.

At the time I had this thing where I didn’t like to eat in front of people, especially the Dakotas and their dad, or kids at school, or in restaurants. Late at night, when Big Mike was asleep or out and the Dakotas were up in their room screaming into their headsets, I’d go down and sit with Amber and together on the couch we’d eat in peace and comfort, not having to hear that the way you’ve arranged your legs under yourself is gay, or that what you’re eating is making you soft, which in Big Mike’s lexicon could mean gay or fat and to him I was both.

Which isn’t the worst thing somebody can say when you’ve got rolls and there’s been rumors about you since you were in third grade and you contracted meningitis. I was friends with this kid Braiden Cartier at the time. We played together during aftercare. As tight as it gets for little kids. I was smaller and weirder and he was very tall and perfect-haired and would only grow taller and more perfect in various ways later on. When I got sick, at first it was unknown whether I had viral (bad) or bacterial (worse) meningitis, until I wound up in Lakeview Regional, where they gave me a spinal tap. But before that happened, Amber and Mike, who I still called Mommy and Daddy, sat there and asked me if I’d maybe shared a drink or some food with Braiden at lunch or aftercare. Then a doctor and a nurse came in and asked the same thing. Which I denied because ew, gross, I wouldn’t share a drink or food with anyone, even Braiden, and also because what is this, 1988, and we’re all drinking out of the proverbial hose. Regardless, these adults heard me say no in a small sick voice and they did not believe me. They could not possibly have believed me, I know, and I couldn’t possibly ever think of them like a mom and dad again, because of what happened next.

The doctor then asked had I ever kissed Braiden Cartier. Bad enough being asked by medical professionals if you had kissed another boy, but then Big Mike shoved in talking about, Did that boy touch you, did he put his mouth on you? This was his version of being a hero, but he didn’t look like a hero, he looked like he was looking at something that belonged in what he called the commode but was sitting here unflushed on a hospital bed not telling the truth. Shortly afterwards I was given what is considered one of the most painful medical procedures going, which I’ve since learned cops administered to fucking serial murder suspects in the old days, to make them confess.

Well, I confessed everything I’d ever felt and many things I’d never done and by the time I got out of the hospital Big Mike and Amber and the Dakotas had spread it all around that I was gay. I tried to correct the record a couple of times, naively believing that if my peers and family understood I liked certain girls as much as I liked boys like Braiden Cartier then maybe they wouldn’t find me so gross. Except to some people, especially my erstwhile family and apparently the certain girls whose names I’d given as proof that I wasn’t totally gay, liking both is even worse.

I went on sneaking snacks at night with Amber, but it never felt safe in the same way again. Plus she was mostly gone on fent by then. She’d slip off for a while and come back to the couch and I’d look over and she’d be nodding, and some nights she wouldn’t come back at all. You’d hear her wake up, whump, in the bathroom after you went to bed. Meanwhile, Big Mike would come back from the fishing camp or work or whatever and tell me I was getting softer. See me sipping a can of Delaware Punch and ask if any other lips than mine had kissed the rim. Catch me eating a candy bar and lay a whole new nickname on me. Butterfinger. Emphasis on the butt and the finger.

I didn’t always just take it, though. I remember one time I bowed up, balled my fists and hiked my shoulders to my ears, and screamed in Big Mike’s face that I hadn’t been eating a fucking Butterfinger because I don’t like how fucking Butterfingers stick up in your fucking teeth, OK? Well, I know how I looked because the Dakotas were filming and made damn sure I saw later how my eyes went pitiful when Big Mike’s goatee closed around his mouth—pinched and hair-ringed as a monkey’s sphincter—and he got down in my face real close, veins risen up his neck and into his forehead like pissed-off ants were tunneling through him, and said murderously slow that he knew for a fact my soft ass had been scarfing down a crispety-crunchety peanut-buttery Butterfinger, or was I calling him a liar in his goddamn house?

I remember seeing Amber over his shoulder, shaking her head at me like, No, don’t. Just agree.

That was the shortest way to a quiet night: Just agree. Believe what someone else says about you, live in their reality no matter how wrong.

So I did—that time and all the others—until the very end.

I hate it, but I miss her. Even if she didn’t stop anyone from calling me Murderbaby, or soft, and even if when she was upset she would cuss not just my supposed father and his whole fucked-up family, but her little sister too. Even if she let her boys use the specter of the vengeful Destiny to scare me. More and more, I think Amber wanted her out there like a warning, like people in the old days would use Rawhead and Bloody Bones to keep their kids from going near the water’s edge.

Like maybe she could see West Florida looming on the horizon, waiting for me. I don’t know. For all their telling it how it was, neither one of my caretakers ever told me the whole story. They never said my grandma Krista was in episodes of shows that ran on the USA Network, that she was in movies, real movies, even if they went straight to video and featured gratuitous bikini scenes and sharks edited together from other shark movies by unscrupulous Italian directors. And they never told me about Pawpaw either, or at least anything other than he’d gone to prison and had three or four wives. They didn’t tell me he’d built a mansion and a neighborhood, the start of a whole new state, and had it all taken away. I don’t think they were trying to be bad, at least with that part. Maybe nobody ever has the whole story about anything, and I don’t think they knew much about the whole West Florida thing. Nobody did, really, until the spring of my last days in Mandeville, when that bastard Troy Yarbrough stole my Woolsack family’s whole idea.

Back then, when I still went to school in what I thought was Louisiana, we had this teacher who wanted to know what we’d do if there was another civil war. Had us take this question home. This was after State Rep. Troy Yarbrough and his bill to create a new state out of the western portion of Florida started to really make the news. The teacher thought that if this bill somehow passed in Florida, and passed in D.C., then the Electoral College would be even more stacked, in her words, than it already was. Stacked against what, we didn’t know.

People wouldn’t take that, she said. People would fight.

Then somebody in the back row farted but no one knew who, and accusations and eventually chairs were thrown and the period ended and we all went on to gym.

Talking about civil war wasn’t anything new. I’d been hearing that shit ever since I was little. Come election time everybody acts like their dog’s just died or like all the dead beloved dogs have risen up from their backyard graves and howled.

Big deal.

For homework that weekend we were supposed to look up articles about how states get made and ask the people in our lives what they’d do in a civil war–type situation. The teacher had showed us clips of little protests happening in Miami, in Orlando, on the statehouse steps in Tallahassee. I knew I’d originated there, in Florida, and my classmates went there on vacation, but none of those places meant a thing to me. Watching at the time, you might get the sense that both sides were primarily in it for fun. The One Florida people were up in the cities from the center of the state to the tip of the peninsula, and it wasn’t like they were being invaded or forced to do anything, just asked to let go of a portion of the state they themselves called Lower Alabama or South Georgia or whatever. What did anyone really have to lose? People had said for years to just let whoever they didn’t like have their own island, or space, or state: round them up, turn them loose, and watch them fail.

I didn’t look up any goofy-ass articles. I had research of my own to do.

Lately, I’d gotten back into checking for updates in the massacre threads, watching clips of Krista’s stuff in secret and studying her face while she had a chain fight on-screen with a futuristic biker girl or was pulled into a frothing bloody sea by a demonic shark, to see if my own face shone through. What I hadn’t done was search for my uncle Rodney, at least not since I was little. Back then about all I’d managed to track down was some high school running stats—no presence on social media, zero images. I mean, I was a nine-year-old, not the FBI, so he might’ve been posting somewhere, but it sure seemed like this Rodney didn’t want to be found and, I guessed, he didn’t want to find me, so I’d given up, until now.

It was the Friday evening before the Dakotas’ eighteenth birthday and I was up in my room with my phone in my hands going, Holyshitholyshitholyshit, because Rodney Woolsack still wasn’t on social—but he was on DU3L. This time when I’d googled him the top results were all from the gunfighting app, every link taking me to a page that said it’d work better if I just downloaded DU3L in the app store. I started kind of vibrating on the bedspread while the loading arrow spun. Sat up and tried deep breathing. Got close to the screen, eyes wide with awe as his profile came up.

Rodney Woolsack was ranked twelfth in handguns in the Northwest Florida region. Here were his gunfights going back a year and a half. How many he’d shot. How many he’d been shot by. His sidearm of choice. His sponsors. A quick interview he must’ve filmed himself. Finally, his upcoming appearances and events, the next of which was the Crescent City Gundown the following Saturday.

I said to myself, You gotta be fucking kidding.

I’d seen gunfights from DU3L before, thanks to Big Mike and the Dakotas and my own curiosity. Just highlights, though. I didn’t do the livestreams or watch training videos or gear reviews. Still, I must admit it had a certain appeal. I don’t know if the ads are right when they say gunfighting brought peace and safety to a dangerous and unpredictable world, but I was glad there was something for mass shooter types to do other than bust into classrooms or wherever and blast random people like me. Now they could put themselves on DU3L and get the kind of antiheroic ending their hearts desired, or the thrill of inflicting themselves on someone else via bullet.

That night I made a fan profile and watched as many of Rodney’s gunfights as I could. The more I saw him draw and fire, his opponents stagger, clutching wounds until the medic came to carry them off or drop clean-shot to the ground, saw him take his share of lead too, always coming back for more, the more a lump climbed up my throat and hung there diamond hard, and I got to thinking about how in a matter of days he’d be just down the road and his profile page had a message button I could just click and say, what exactly? If he’d wanted to find me he’d had the better part of thirteen years, and besides, what did I need another violent macho lunatic in my life for? I had plenty of them at home.

I was feeling all wound up and confused, so I went downstairs, where the Dakotas and their dad were on the living room couch watching something on one of their phones. The Dakotas sat on either side of Big Mike and they were all three hunched over, staring intently. I hung behind the couch and tried to glimpse what was happening on the screen.

The camera was on a dirt track that looped a grassy infield filled with people turning in the direction of a cloud of dust and smoke. None other than Rep. Troy Yarbrough gunning around the bend in an All-Terrain Apparel Bombardment Vehicle with toothy black wheels and a custom-mounted T-shirt Gatling gun and integrated trigger system. Coated in red and white, with #BestFlorida emblazoned on its roll bars and the logo of the red wolf prowling across the hood, the vehicle churned a stream of dirt behind it like bilge as Troy made toward the stage in a jackknife drift, firing T-shirts into the crowd. I watched hands shoot up, grabbing for the bundled shirts, scrums breaking out all around him. Men tugging off their jackets, guts wagging as they tore the bands from the fired shirts and tugged them on. The red wolf there too, on the shirts, loping midstride. Another version of it hanging at the bottom corner of the screen.

I realized I’d been seeing that wolf around on bumpers and hats without knowing what it meant. I’d assumed it was some gun or hunting shit.

Rep. Yarbrough got down and climbed onstage and was given a mic, and he began to speak and point. His sleeves were rolled in a Marine Corps tuck, and from the tips of his fingers to his eye sockets he was nothing but muscle and bone. Presently, he was joined onstage by a woman in a blush business suit with jagged spray-held hair the color of dried blood, leading on a thin leather leash an actual living red wolf. The Yarbroughs, husband and wife, cared so deeply about West Florida and its environment that they’d put their own money into researching and developing a hybrid strain of these creatures, with an aim to reintroduce packs across the Gulf Coast.

The crowd roared and the wolf shrank back and sat at the woman’s feet as Rep. Yarbrough gave her a one-arm hug and then began to speak. You could see the sinews fluttering in his cheeks, if you could call them that. The man looked flayed.

“That’s sick,” I said.

All three of them turned.

“Sick like good?” said Dakota James.

“Like he looks gross,” I said. “Like he’s super skinny.”

“Dude’s fricking ripped’s what he is,” said Big Mike.

“Vascular,” said Dakota Blake.

“Striated,” said his brother.

I said, Speaking of which, and told them about my homework, asked them what they’d do in a civil war. Instead of answering, Big Mike turned back around and hit play on the video, and they all three resumed watching. I asked again, for real, and the Dakotas hooked their elbows over the back of the couch and asked me what I’d do.

I said I guessed I’d probably fight and they said bullshit I would.

So I asked what they thought I’d do, then, and the brothers looked at each other for a second and said I’d fill my pants immediately. Dakota James broke into a freestyle built around the end rhyme of poo and you.

“Savage,” said Big Mike, his voice weighted with approval. Anyway, he added, it wouldn’t be much of a fight because whoever was on the other side would be such beta-ass pussies that the war couldn’t last too long.

He wasn’t looking at me but I could feel his glare burning through the wrinkled back of his head. I worked on that diamond in my throat and left Big Mike and the boys downstairs. We had no idea what was coming, none of us.

Not a fucking clue.

__________________________________

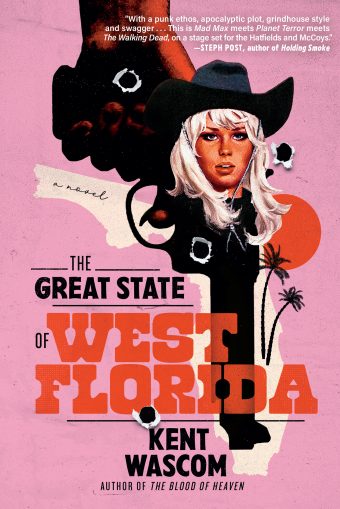

From The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom. © 2024 by Kent Wascom. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Black Cat, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.