The Gift and Curse of Being a Truth-Teller: On Receiving an Autism Diagnosis as an Adult

Michelle Gallen on Heroic Honesty, The Emperor's New Clothes, and Writing Her Debut Novel

I’ve always been fascinated by the fable The Emperor’s New Clothes, in which a fat old emperor is conned by swindlers who promise to weave him a beautiful outfit that is invisible to stupid people or those unfit for their job. The emperor, his lackeys, and the townspeople all pretend to see the clothes until a child exclaims, “But he hasn’t got anything on!”

As a small girl, it astounded me that the hero of this story did not have to climb a mountain, part the seas, or travel to Mars to be heroic—they simply point out the obvious, something most children are very good at. I wasn’t surprised that the adults didn’t speak out: I learned early that many people protect their status quo no matter what it costs others. I didn’t understand then—and still don’t understand—why this is OK.

I’ve always felt compelled to speak what I believe is the truth. I’ve rarely been treated as a hero for this. Adults who speak the truth to other adults—whether in the workplace, politics, or during dinner parties—are often silenced by bullying or exclusion. It’s not fun. I’ve spent my life feeling like an alien, enduring painful, puzzling social experiences, and using a range of masks to “perform” as “normal” in front of people. I’ve burned out over and over again. Medical professionals have repeatedly dismissed me with various diagnoses, ranging from “hysterical” (not in a good way), borderline personality disorder (a frequent misdiagnosis for autistic women), anxiety and depression.

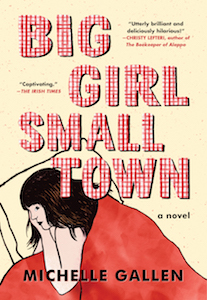

But late in 2017, when a blazingly intelligent female relative (who had long been struggling in life) received a relatively late diagnosis of autism, I decided to learn more about the female presentation of this neurological condition. I was already familiar with the male presentation of autism—most of the autistic males close to me were diagnosed—and therefore supported—early in life. I didn’t expect, when reading about autism in women, for my heart to split wide open. I first recognized Majella, the unlikely hero of my then-unpublished novel Big Girl, Small Town, and then recognized myself; I realized that my novel is a portrait of an undiagnosed autistic woman written by an undiagnosed autistic woman.

During the summer of 2019, while editing Big Girl, Small Town for publication, I realized much of Majella’s life was needlessly painful and her potential stymied by not having a diagnosis of autism; a lack of diagnosis means that she cannot access the supports and accommodations that can be transformative for autistic people. After I submitted my edits, I decided to undergo an autism assessment myself. But due to a fractured medical history and nomadic adult life, I could not provide what most psychologists demand before starting an assessment: family testimony of my behavior as a child, and professional medical notes. It took until late 2020—at the age of 45—to find a psychologist who was willing to assess me based on all I had: my own testimony.

I told the psychologist a story my grandmother often repeated to me, in which I was playing at her feet on a rug. My father walked into the room and tripped on the rug. “That fucken rug!” he said, kicking it. I—just three years old—looked up and said, “Daddy, it’s not the rug’s fault that you tripped. It’s your own fault. You shouldn’t be angry with the rug—you should be angry with your feet.” My grandmother always laughed heartily when she told this story, amused by the cheek of me lecturing my mathematician father. My father (a man who wasn’t used to adults speaking back to him, let alone preschoolers) was not so amused. It took me decades to figure out the “right” answer would have been something like “Poor Daddy! The bad rug! Are you OK?”

I recalled attending a dinner party in Ireland years ago, where one of the guests, in response to a conversation about some of the challenges faced by “poor people,” comforted herself and the other dinner guests by saying, “Oh, but we are all middle class here.” I took it upon myself to explain to the woman—and everyone else around the table—how the British class system was invented by the English, how the Irish—who for centuries were considered subhuman by the English—were so lowly they were not included in the class system, and I noted that her identification with the British class system could be a post-colonial hang-up: perhaps after centuries of occupation, her self-value was so low she looked to her former oppressors for personal and social validation. My contribution was greeted with silence.

I’ve been asked why can’t I just keep quiet if someone says something that I feel is factually inaccurate. But I find it almost impossible. My mind fixates on the inaccuracies and I tense up until I burst out with the “truth.” I feel trapped when people engage in insincere conversations, such as complimenting someone they were privately insulting five minutes previously. I have jumped out of bathroom windows to escape dinner parties. I have fled restaurants and pubs and gone running through streets to purge the pain, to feel air enter my lungs, oxygen coursing around my body.

Speaking the truth as I see it is both a gift and a curse.

I don’t just struggle in social gatherings. Despite a successful career in tech, I’ve always found office jobs unbearable. It’s excruciating to sit under fluorescent lights processing the noise, constant interruptions, and endless small talk. But by far the biggest pain is office politics. I was in my forties before I understood the role that office politics play in the execution of projects.

I told my psychologist about an incident that happened when I started a junior role in the BBC. A former TV producer asked me—a tech fiend and incorrigible geek—for feedback on several web pages she had designed. I examined the pages in minute detail, then wrote a report cataloguing the many flaws related to the language and images used, accessibility and technical build. I noted each typo and grammatical error, made suggestions about usability, and gave the report to the producer, expecting her to be as pleased as I would have been to receive a detailed document to help me improve my product. But at a meeting later that day, the producer went around the table, asking each team member for verbal feedback. One by one, my new colleagues said things like, “it’s great,” “so pretty,” “a lovely job.” When it came to my turn, the producer brandished my report in the air, then dropped it on the table saying, “Michelle has already given plenty of feedback.” Hilarious, now, in hindsight, but painful for everyone at the time.

Speaking the truth as I see it is both a gift and a curse. When I join a project, I come to it with the hope I can deliver the best working experience and product possible. I am not interested in basking in glory. I am not interested in appearing good. I find flattery unbearable. But I’m also gullible. I take people at face value. I believe in the project’s stated mission, which, all too often, is not aligned with the personal interests of competing team members.

I have learned over the years—slowly, painfully and explicitly—how to parse office politics. How to read between the lines of a project brief to discover what the “real” mission might be. To figure out who the actual stakeholders are (clue: they are not always listed in the stakeholders’ list in your project spec). To—and this hurts most—create not the best product (the one that the end users need—the one that uses the best architecture and technology)—but the product that will keep my superiors happy.

I see now that I have spent 45 years learning how to fit in both socially and professionally. I’ve learned slowly (painfully) how to appear “normal.” I use a range of masks to hide my anxiety, confusion, fear, and self-doubt. I’ve learned to hide my raging inner critic behind a smile and quick wit. But during the process of my autism diagnosis, I dropped my masks and let the “real” me—the too curious, too honest, too talkative, too twitchy, too enthusiastic, too geeky, too gullible, too anxious, too emotional too much person—speak with the psychiatrist. The experience was like my best writing days (or worst drunken nights) when my brain blazes and I am possessed by words and high on my world, an experience that is glorious, exhilarating, and utterly exhausting.

When my psychologist gave me a diagnosis of autism, I did not feel relief. I felt seen in the awful way I imagine the Emperor feels seen when the child shouts “But he has nothing on.” It’s a frightening feeling to have my masks and borrowed gestures stripped away. I have spent months since my diagnosis trying to imagine how I will now function outside the safety of my domestic bubble once the pandemic recedes. But the success of Big Girl, Small Town—an atypical book by an atypical writer—has given me confidence that there is a growing acceptance in the world for neurodiversity, more understanding of the strengths as well as the challenges.

Readers of all ages and nationalities—from Ireland, the UK, and the USA—have reached out to me to tell me how they fell in love with Majella. They’ve laughed at Majella’s deadpan sense of humor and unsentimental take on life, and felt heartbroken for her grief. They’ve told me they want to be her friend, that if they could, they would reach out to Majella and support her. The reader reception to Majella has revealed to me she—we—have a tribe of thousands of people who love other people not for saying and doing the right thing, but for being exactly who they are.

__________________________________

Big Girl, Small Town is available from Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2021 by Michelle Gallen.

Michelle Gallen

Michelle Gallen was born in County Tyrone in the mid-1970s and grew up during the Troubles a few miles from the border between what she was told was the"‘Free" State and the "United" Kingdom. She studied English literature at Trinity College Dublin and won several prestigious prizes as a young writer. Following a devastating brain injury in her midtwenties, she co-founded three award-winning companies and won international recognition for digital innovation. She now lives in Dublin with her husband and kids.