The Fraught and Risky Business of Spotting a Historical Fake

Nathan Rabb on What He Learned From His Father's Bookshelf

The signature looked pretty good I thought. It read “A. Lincoln,” as Lincoln’s letters always did. If you see a letter—not a formal document—signed Abraham or Abe, run in the other direction. The Lincoln ended with a two-tiered signature, with the final two letters set on a slightly higher plane. Indeed, Lincoln’s autograph typically takes three distinct steps upward, and a flat signature is suspicious. This had those steps. Yet I had a feeling in the pit of my stomach.

The writing had a labored look to it throughout the letter. A few letters looked deliberate, even traced, and the dateline was scrunched. The lines weren’t straight—they bobbed and weaved up and down. Something was wrong. Yet this was a famous letter, widely published, being sold by a reputable dealer, referenced in one of the biographer and scholar Carl Sandburg’s great works and illustrated there. My father had suggested, before seeing the scan, that we buy it. This important letter was about Lincoln’s pardoning a soldier to be executed during the Civil War, an act for which the president would earn a reputation for fairness and clemency. Yet it wasn’t passing the blink test.

On my first day on the job, my dad had walked over to his bookshelf of reference works, many now rare and out of print, and picked one out.

“Read this,” he said.

Many years earlier, when I was about eight years old, my father began putting together what would become a large reference library, with books about authenticity, great auction catalogs of past years, biographies of famous people, and illustrations of authentic autographs, against which he compared the autographs he would collect. By the time I joined the business, his walls were covered with books.

He reveled in discussing the history of the field. “Aristotle collected manuscripts and maps; so did the ancient Romans,” he said. “The elder Pliny wasn’t merely a collector of autographs, but made the earliest known comments on their rarity, remarking that in ancient Rome, in their bookshops, the letters of Cicero, Virgil, and Augustus Caesar weren’t uncommon, but that those of Julius Caesar were very rare.”

It was no small thing to evaluate the holdings of a seasoned dealer, a generation older than me, and pronounce his material fake.As Mt. Vesuvius erupted, and Pompeii was being buried, Pliny the Elder was across the bay with his book and document collection. His nephew Pliny the Younger wrote:

On 24 August, in the early afternoon, my mother drew his [my uncle’s] attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance. He had been out in the sun, had taken a cold bath, and lunched while lying down, and was then looking at his books. . . . My uncle’s scholarly acumen saw at once that it was important enough for a closer inspection, and he ordered a boat to be made ready. . . . He hurried to the place which everyone else was hastily leaving, steering his course straight for the danger zone. He was entirely fearless. . . . Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames: then suddenly they were in shallow water, and the shore was blocked by the debris from the mountain.

My father’s interest in the history of the sellers of history has made him something of an expert on the subject. While Europeans began opening historical shops in the early mid-19th century, the historical professional trade in the United States was decidedly newer. The early collectors, motivated by a growing realization of the importance of the American story and the collecting spirit of the Victorian era, put together collections that would today be nearly impossible to find. The material cost little, $5 or less for a letter by George Washington, for example. The Victorians notoriously clipped signatures off documents. William Sprague, America’s first renowned collector, wrote to George Washington’s biographer Jared Sparks asking for a sample of Washington’s handwriting for his growing collection. Sparks obliged by taking a scalpel to Washington’s inaugural speech, slicing it into collecting pieces, an unfortunate symbol of the era. All this my father told me the first week on the job, perhaps even the first day.

The first book my father pulled off his shelf for me was a battered copy of a memoir by early collector Adrian Joline, Rambles in Autograph Land. Joline had been alive during the lifetime of Darwin and a bit after. If he wanted a letter from Theodore Roosevelt, Joline had no need to buy one—he’d write the White House himself. His was a noble passion, an educated pursuit. Joline decries the Victorian collecting mentality and writes of the difference between collecting for the sake of collecting and the true hunt—the search for the history and its meaning.

But the book I liked the most was called Great Forgers and Famous Fakes, written by 20th-century dealer Charles Hamilton, who died during my lifetime and whom my father knew. Hamilton gives detailed accounts of some of the scoundrels of the age, men adept at handwriting and forging, the equivalent of an actor doing a great impression, but with a more sinister intent and legal implications. Hamilton writes about men content to steal and misrepresent.

From him I first learned of Joseph Cosey. Cosey was the greatest forger of his generation, Hamilton felt. Cosey’s works appeared (and still appear) in major auctions and continue to dot the landscape. Many libraries have his forgeries without knowing it.

And if you wanted one in the early 20th century, you needed only to pull up a stool at the bar, where Cosey could often be found, and buy the man a drink. It could plausibly be said that Abraham Lincoln posthumously fueled Cosey’s alcohol problem.

“Practically everybody has been stung by Cosey,” Mary A. Benjamin told Hamilton. She was heir to the Walter Benjamin firm, the first major dealer in the United States. Cosey loved Lincoln, but he also forged the letters of George Washington, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and many more. He had access to period paper, period ink, and he’d practiced so extensively that he could write full letters fluidly. Cosey wasn’t his real name. It was Martin Coneely.

“Dad, I don’t know why yet, but there’s something wrong with this letter,” I said. “We shouldn’t buy it.”And yet, in spite of his obvious talents, Hamilton wrote, Cosey had an Achilles’ heel when it came to Lincoln. He never got the signature just right—that three-stepped shape. It goes up almost uniformly. Lincoln would write the tent of the A, place a dot or two after the letter, then cross it with a counterclockwise loop. From there, without picking up the pen, he’d start the L of Lincoln and keep it on a platform raised above the A, before proceeding through the o, from which he’d step up again for the ln. Cosey wrote the entire name on a horizontal line.

Even Cosey wasn’t perfect. Everyone has an Achilles’ heel.

Eight years later, I was staring at that Lincoln letter.

“Dad, I don’t know why yet, but there’s something wrong with this letter,” I said. “We shouldn’t buy it.”

It was no small thing to evaluate the holdings of a seasoned dealer, a generation older than me, and pronounce his material fake. I’ve done that since, but I’d never done it before. I had to be sure. Moreover, this was not an unknown letter. It had come from the collection of the revered Oliver Barrett. Barrett put together the most significant collection of Lincoln documents ever, then or since, a collection he sold for many millions. He was friends with Carl Sandburg, and Sandburg had reproduced this very letter in his book Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. The Papers of Abraham Lincoln noted the existence of this letter and cited the Barrett collection as its source.

I looked at the handwriting. Many of the letters superficially looked right. This wasn’t traced. Care had been taken to re-create a few of Lincoln’s more idiosyncratic letters, such as the distinct capital F. The paper had been folded properly to mimic a piece that had gone through the mail. But from there the similarities to an actual Lincoln letter were few.

The entire letter sloped down, left to right, as if the writer had lost interest at the end of each line. Some of the letters were just wrong if you looked at them individually. The dateline was smooshed together, as if the writer had run out of space. A couple of the letters were shaky, and the entire letter was uneven. In Lincoln’s time, people studied handwriting, and the lines of a letter were straight, not uneven. This was the first time I had this instinct, this gut feel.

It took about an hour of active discussion with my father for me to become fully confident in my assessment. “Do you think it’s Cosey?” my father asked.

I looked at the signature. This forger knew what Cosey never got: Lincoln’s signature was three stepped. Yet Cosey’s letters were far more convincing taken overall. Cosey’s forgeries fail on one elemental level, the autograph, but generally succeed in the overall texture of the handwriting. This sloppy attempt was both corrective of Cosey’s work and not worthy of it.

We didn’t buy the letter, and the dealer who’d listed it for sale agreed with my assessment after I explained my thinking. But more than that, the forgery matched none of the known examples published in my father’s extensive library. We’d found a new forger, an unknown counterfeiter. The dealer pulled it from his inventory, acknowledged his mistake, and the episode ended.

All this I began to learn on my very first day at the office, thanks to my father’s bookshelf.

__________________________________

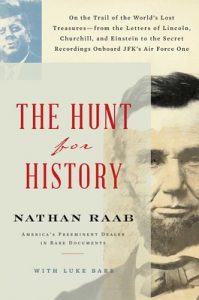

Excerpted from The Hunt for History: On the Trail of the World’s Lost Treasures—from the Letters of Lincoln, Churchill, and Einstein to the Secret Recordings Onboard JFK’s Air Force One, by Nathan Raab with Luke Barr. Copyright © 2020 by Nathan Raab. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.