The Forged Letter that Began a Mormon Succession Crisis

Miles Harvey on the Life and Times of James J. Strang

On July 9, 1844, a letter from a dead man arrived at the post office in Burlington, Wisconsin, forty miles southwest of Milwaukee. Addressed to “Mr. James J. Strang,” it had been postmarked three weeks earlier in the Mormon city of Nauvoo, Illinois. The dead man was Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He had written the letter nine days before his murder, but already he could see what fate would soon befall him. “The wolves are upon the scent, and I am waiting to be offered up,” he confided to Strang, whom he addressed as “My Dear Son.”

Indeed, it was the prophet’s premonition regarding his imminent demise that had prompted him to write. “In the midst of darkness and boding danger the spirit of Elijah came upon me,” he explained, “and I went away to inquire of God how the church should be saved.” According to Smith, God’s voice came in reply: “My servant James J. Strang.”

This mysterious epistle would go down as “one of the most important—and controversial—documents in the history of the Mormon religion,” in the words of one modern observer. If the letter was to be believed, 31-year-old James Strang—who had disappeared from western New York less than a year earlier, with creditors close on his heels—was now the rightful heir to a church of more than 25,000 members worldwide.

How had this seemingly impossible turn of events come to pass?

One thing seems certain: Strang had not gone west with the goal of becoming a prophet of God. His original intention, he later told an interviewer, was to make a fortune in what had been one of the era’s fastest-growing industries, the construction of canals. The success of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, had set off a canal boom in the United States, with more than 3,000 miles of these inland waterways constructed by 1840. Strang hoped to use a family connection to get work as a contractor on the Illinois and Michigan Canal, an ambitious effort to link the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

That family connection was his father-in-law, the redoubtable William L. Perce, a longtime canal contractor with a remarkable record of graft and profiteering at public expense. Because canal projects were so massive, they were usually funded by individual states and run by political appointees, making the system ripe for corruption. As a superintendent of repairs on the Erie Canal in the late 1820s, for example, Perce was able to hand out contracts to his cronies and to himself. Even by the standards of a business notorious for its fraud and graft, he binged at the trough with impressive gluttony.

A New York lawmaker later summarized a state investigation into Perce’s tenure as a superintendent, which concluded that fraud and profusion in the expenditure of moneys . . . had been fully proved and established; [and] that such fraud and profusion had not been moderate and occasional, but systematic and frequent and varied. Sometimes the fraud was “ingenious and covert,” at other times “bold and barefaced”; and that such fraud mingled in almost every considerable transaction done by that superintendent.

Consequently, in August of 1828 Perce was arrested, and “not being able to procure bail, he was committed to the [jail] of the county of Cayuga,” according to the New York State attorney general. Six months later, he was ordered to pay $40,000 in damages—more than $1 million in today’s dollars—“for monies which he had fraudulently obtained from the public treasury . . . by means of false and double vouchers.” But being “utterly unable to pay the judgment, or any part of it,” he was still behind bars a year and a half after his arrest.

Modern researchers have identified the letter from “Joseph Smith” as a forgery.

Perce, in short, was a scoundrel—the first of many colorful charlatans who would soon gravitate toward Strang, like rats to rotten meat. During almost any other age, the contractor’s well-publicized arrest might have meant a quick end to his career in the canal business. But the antebellum era was full of figures with a special gift for slipping back and forth between disrepute and respectability. By 1835, Perce was once again working as a contractor, this time on the James River and Kanawha Canal in Virginia, where he appeared to be “getting rich,” according to Strang. It wasn’t long before the unregenerate cozener took the money and ran. But somehow that didn’t stop him from landing yet another job as a contractor, on the Illinois and Michigan Canal—with predictable results. Soon, a newspaper in Illinois would publish a story about Perce under the ironic headline “A Distinguished Character.”

The article’s purpose, according to the editors of the Ottawa Free Trader, was “simply to let numerous strangers, who are now locating on the line of the canal, know something about a notorious swindler,” whose name was “synonymous with fraud and knavery.” So abysmal was Perce’s reputation, the paper added, that “there is hardly a farmer or day laborer who has ever dealt with him but can testify to his villainy.”

This, in sum, was Strang’s father-in-law and the man he’d been counting on to help him find work, and maybe a fast fortune. But the fact that those plans fell through appears to have had less to do with Perce’s bad reputation than with Strang’s own bad luck. While his in-laws had preceded him to Illinois, his own arrival there with his family in the fall of 1843, at the age of thirty, happened to coincide with a two-year suspension of work on the Illinois and Michigan Canal, due to financial problems in the state. Once again, Strang had failed in a career—this time, even before it could begin. When the canal work that Perce had long promised failed to materialize, Strang apparently saw no reason to settle with his in-laws in Illinois. Instead, he moved the family north to Burlington, Wisconsin, where both the town and its newest resident would soon be utterly transformed.

*

Located at the confluence of two beautiful rivers, Burlington had been settled by a group of pioneers from Strang’s home area of western New York. Arriving in 1835, before Congress had incorporated Wisconsin as a US territory, these newcomers took over land that, until a recent treaty, had belonged to Native Americans. There they set about building their own community in the wilderness, fifteen miles north of the Illinois border. Like Strang, who had years earlier declared himself a champion of “universal liberty,” many of these settlers were abolitionists, some of them having already established a semi-secret organization for assisting escaped slaves. Unlike Strang, however, they were Mormons—early converts to the faith whose religious enclave in Wisconsin now included about 100 members, including one of Strang’s closest childhood friends.

Benjamin Perce—the younger brother of the corrupt canal contractor and the uncle of Strang’s wife, Mary—had done fairly well for himself on the frontier, speculating in land, opening a store, and serving as a justice of the peace. He also owned one of the area’s few frame homes, which he now opened to Strang and his family. After settling in, the newcomer quickly set up a law practice with a fellow attorney named Caleb P. Barnes, whom he had known back in New York. The frontier offered Strang a reprieve from the past and a new start. Free from the stain of his previous misdeeds and failures, he attempted to revive his legal career, arguing cases in both Wisconsin and Illinois. One judge would later recall him as an attorney of “great shrewdness,” who was “continuously bringing up unexpected points in law cases, and using arguments that would have been thought of by no one else. I think he liked the notoriety that resulted from that sort of thing.”

Strang might never have had a career as a holy man, in fact, had a legal case not required him to travel to Ottawa, Illinois. There he happened to meet up with one of his Mormon neighbors from Burlington, who persuaded him to make a 175-mile detour to Nauvoo to hear Joseph Smith preach. The journey came at a difficult time in Strang’s life. Shortly after the family’s arrival in Burlington, his eldest daughter, just five years old, had become ill and died—an event that “seemed to wear heavily on him,” in the words of his sister. But if this loss had put him in a reflective mood, it seems not to have brought him any closer to God. When he arrived in Nauvoo in February of 1844, Strang was, by his own estimation, “an inveterate unbeliever and opposer of the Mormon faith.”

*

It must have been exhilarating for Strang to emerge from the prairie into the bustling metropolis of Nauvoo. With two sawmills, a flour mill, a foundry, a brewery, a brick factory, a tannery, a bookbindery, and a match factory, the city was “growing like a mushroom (as it were, by magic),” according to a local resident. Founded just five years earlier, after Joseph Smith and his disciples had been forced to flee earlier headquarters in Ohio and Missouri under the threat of violence, Nauvoo now rivaled Chicago as the most populous city in Illinois. All over town, people from as far away as England were erecting houses of brick, stone, lumber, and logs. A huge new temple was half-finished, and a three-story Masonic Hall was nearly complete. Also under construction was the Nauvoo House, a hotel and tourist center for travelers.

Like Strang, most visitors came to Nauvoo in hopes of meeting the famous prophet. One man who arrived in town around that time described Smith as a “sturdy self-asserter” who had “a strong mind utterly unenlightened by the teachings of history.” Another pilgrim characterized the founder of Mormonism as “a mixture of shrewdness and extravagant self-conceit, of knowledge and ignorance, of wisdom and folly.” A third visitor maintained that Smith was “a great egotist and boaster” whose “language and manner were the coarsest possible,” while a fourth found him to be “a compound of ignorance, vanity, arrogance, coarseness and stupidity and vulgarity.”

Strang didn’t record his own impressions of the prophet. Nonetheless, something extraordinary happened at their meeting, perhaps even something miraculous—something that altered the course of Strang’s life and has confounded historians ever since. Strang himself would have little to say about what did in fact transpire between the two strangers, other than to tell one journalist that he “contended with Smith for a considerable time, but was at last converted to the faith.”

What was behind this conversion? Why did a skeptic like Strang suddenly open his mind to the Mormon message? How could it be that a man who had spent his entire adult life lifting his “puny arm in rebellion against the Most High God,” in the words of his devout Baptist sister, would suddenly drop to his knees with the zealotry of a true believer? Was he, as that same sister would suggest, hoping to fill a spiritual void caused by the death of his daughter? Did he, like so many others before him, succumb to the force of Smith’s personality, the allure of his words, the charisma that circled him like a silvery halo, the mysteries and mystifications that enveloped him like the cigar smoke of a card sharp? Or was a more complicated dynamic at work? Could it be that in this inventor of a new bible, a new religion, a new city, and a new self, in this empire builder who was running for president of the United States, James Jesse Strang recognized, at long last, a way to realize his own dreams of royalty and power?

Many years later, an acquaintance would insist that the whole thing began as a simple real-estate swindle, set up by Strang and two other men—childhood friend Benjamin Perce and law partner Caleb Barnes. According to this witness, Barnes once confided that the initial intent of the scheme was to draw Mormon pilgrims to Burlington, thus drastically inflating local property prices and making the three men rich. “Their aim, in the first place,” claimed the friend, “was to have Joseph Smith appoint a gathering place, or Stake, on their lands, but as Smith was killed about this time they changed their plans and concluded to make Strang Smith’s successor.”

Whether this version of events, recounted more than forty years after the fact, has any validity is one of the many mysteries surrounding Strang’s conversion to the faith. What we know for certain is that on February 25, 1844, Strang went to the basement of Nauvoo’s unfinished temple, where, in a wooden font resting on twelve wooden oxen, he was baptized by Joseph Smith. We know that a week later, on March 3, he was ordained as an elder of the church by Hyrum Smith, the prophet’s older brother. We know that during Strang’s visit, which ended in late March or early April, long-simmering antagonisms between city residents and their neighbors reached full boil, with anti-Mormon agitators demanding decisive action against what the New York Sun called “a great military despotism . . . growing up in the fertile West.” We know that Nauvoo was also the scene of internal strife, thanks in part to the worst-kept secret in town—the practice of polygamy by Smith and other church leaders.

We know that in June of 1844, Mormon dissidents published a paper called the Nauvoo Expositor, which accused the prophet of introducing “false and damnable doctrines into the Church.” We know that after a single issue of this new journal, the Nauvoo City Council, at Smith’s behest, ordered the printing press destroyed, precipitating an armed standoff between Smith and Illinois authorities. We know that on June 24, the prophet surrendered to officials in the nearby town of Carthage on charges of inciting a riot. We know that Smith informed bystanders that he expected to be murdered by anti-Mormon mobs—and that three days later his premonition came true. We know that he died without publicly naming a successor. And we know this, too: in July of 1844, James Jesse Strang started telling all those who would listen that the martyred prophet had secretly placed him in charge of the church. For anyone who doubted this sensational claim, Strang was prepared to offer physical evidence as proof.

*

Until that letter from Joseph Smith arrived at his door, Strang’s life had been one long string of failures. But in a strange way, all those stumbles and missteps had prepared him for this pivotal moment, making possible everything that was to follow. Growing up in the Burned Over District’s frenzied atmosphere had not only exposed the young atheist to the rhetorical powers and crowd-manipulation techniques of revivalist preachers; it had also imbued him with a millennial sensibility and opened him to a variety of nontraditional religious sects and self-made messiahs. Working as a frontier lawyer taught him how to navigate the legal system, how to argue persuasively, how to make even the most absurd case seem plausible. Editing a newspaper honed his already strong writing skills and granted him an insider’s view of a communications revolution that was beginning to reshape American culture. And serving as a U.S. postmaster—well, that was perhaps the most useful training of all.

Modern researchers have identified the letter from “Joseph Smith” as a forgery. The main body of the text is written in print lettering rather than in cursive script—a style of penmanship so unusual for the prophet and his secretaries that no other examples are known to exist, according to one scholar. The signature, moreover, “bears no slightest resemblance to that of Joseph Smith,” in the words of another expert. And the two sheets of paper used in the letter are from different kinds of stock.

Strang was asking Joseph Smith’s faithful followers to believe the all-but-impossible—that the prophet had handpicked a complete outsider, a neophyte unknown inside the church, as his successor.

But in some ways, the fraud is quite a clever one. Envelopes and postage stamps were not yet common in 1844, so letter writers often left one side of the outer sheet blank, then folded it in such a way that it could be used for the address and postmark. And in the case of “the letter of appointment,” as Strang soon began calling it, the postmark, hand-stamped in red ink, appears to be authentic. This seems to indicate that someone did indeed send the cover sheet to Strang from Nauvoo on June 19, 1844, even if the inside sheet was a total fabrication. And who, after all, would know better how to pull off such a fraud than someone who had spent several years as a US postmaster?

Strang was asking Joseph Smith’s faithful followers to believe the all-but-impossible—that the prophet had handpicked a complete outsider, a neophyte unknown inside the church, as his successor. But in antebellum America, reality was porous. The seeming impossibility of a proposition did not always prevent its acceptance as truth. Indeed, in many ways Strang’s ensuing career would parallel that of the famous showman Phineas T. Barnum, who in 1842 and 1843 drew thousands of customers to his American Museum in Manhattan to witness “the greatest curiosity in the world,” the preserved corpse of a mermaid. In reality, this “fabulous creature” was an expertly crafted hoax, pieced together from the torso and head of a juvenile monkey and the tail of a fish. Barnum, of course, knew that the object was not genuine. But as he made clear in a conversation with a scientist he consulted before purchasing the mermaid, possibility—not authenticity—was his article of faith:

I requested my naturalist’s opinion of the genuineness of the animal. He replied that he could not conceive how it was manufactured; for he never knew a monkey with such peculiar teeth, arms, hands, etc., nor had he knowledge of a fish with such peculiar fins.

“Then why do you suppose it is manufactured?” I inquired. “Because I don’t believe in mermaids,” replied the naturalist. “That is no reason at all,” said I, “and therefore I’ll believe in the mermaid.”

In the months to come, James J. Strang would ask thousands of Americans to believe in the possibility of an object no more authentic than Barnum’s outlandish monstrosity. But something strange was happening to him now. He, too, was transforming into a new kind of creature, a stitched-together composite of the man he’d always been and the man he’d always dreamed of becoming. Other puzzling occurrences would soon follow.

__________________________________

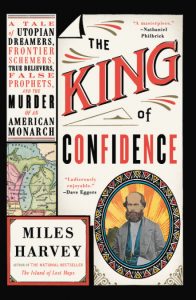

From The King of Confidence by Miles Harvey. Used with the permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2020 by Miles Harvey.

Miles Harvey

Miles Harvey is the author of The King of Confidence, the national and international bestseller The Island of Lost Maps and the recipient of a Knight-Wallace journalism fellowship. His book Painter in a Savage Land was named a Chicago Tribune Best Book of the Year. He teaches at DePaul University.