This used to be a place called the Forest of Wild Birds.

Of course, that wasn’t its official name—it was just what everyone in the area, including the people at Tokyo Electric, called it. A grand forest once grew here, and you could hear birdsong day and night.

Several times a year, they would open the area to the public, and families would come and enjoy themselves. They would spread blue tarps on the grass and stare up at the mountain cherries in full bloom. People would braid flowering white clover into crowns to place on their children’s heads.

This place is also the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, known in the industry as 1F.

Its grounds are extensive, and they say they once overflowed with green.

*

In the spring of 2017, I took Route 6 north from Iwaki Station to visit the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It was April—the government had just recently declared part of the city of Tomioka to no longer be a nuclear exclusion zone. The launching point for tours of the nuclear power plant had long been the J‑Village athletic center, which, following the Fukushima disaster, had been used as a relay point for those working to clean it up. But ever since Tokyo was chosen as the site for the next Olympics, J‑Village had been undergoing hurried reconstruction so it could be used again for athletics (this led eventually to it being made the Olympic torch relay starting point).

So instead, I was heading toward the former “Energy Museum” at the TEPCO Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant (2F). It juts at a sudden angle to a shopping mall with a sign advertising atomic sushi. The museum is like a fantasy of Western architecture, a set of three conjoined buildings painted in pastels that wouldn’t be out of place in Disneyland. Asking about it, I learned that the three buildings were modeled after the homes of Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, and Thomas Edison. These days, it has been reopened as a Decommissioning Archive Center, and the public can visit it whenever they wish. Admission is free.

I was guided into the closed Energy Museum for the orientation before the power plant tour. Entering a room at the end of the hall, I was confronted with walls still decorated with anime‑inspired images. I learned about the decommissioning process and what to pay attention to during the tour of the power plant while surrounded by storybook images of blooming flowers and freshly baked bread.

Cameras and cell phones were strictly prohibited—only pen, paper, and a radiation dosimeter were permitted. We all climbed into a small van with plastic‑covered seats and headed toward the power plant grounds.

*

The 3/11 Great East Japan Earthquake and the ensuing nuclear disaster at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant—I remember the images I saw on the news: debris, ruined buildings, and, as if to cover over the wreckage, encroaching vegetation. Wild animals and animals left behind by evacuated residents roamed the abandoned streets, including cows who’d escaped their farms, dogs and cats left behind by their owners, and wild boars taking up residence in people’s homes. Any humans I saw were dressed head‑to‑toe in pure white hazmat suits. In other words, the “Fukushima” in my head was an irradiated landscape, irrevocably contaminated. But during the tour I never had to change into a hazmat suit even once. I didn’t even have to wear a mask. And the landscape that greeted me at the famous Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, far from being overgrown with vegetation, was a sci‑fi expanse of smooth, silvery cement as far as the eye could see.

We passed through several gates and checkpoints and eventually arrived inside the facility’s grounds. We were brought into a prefab building there. It was an enormous service area, nine floors high and able to accommodate up to 1,200 people at a time. Men working at the nuclear plant passed through a checkpoint that was a radiation dosimeter as they came and went. It was so clean and brightly lit, it reminded me of a convenience store—and in fact, there was a convenience store in it. A Lawson. I was told it had just opened for business.

I gazed at the illuminated blue‑and‑white sign. It was exactly like the one in my own neighborhood back in Tokyo.

*

From the building, we were driven (in a different van—though the seats were covered in plastic in this one too) around the grounds to view the facility. Looking out the van windows, all I saw was a single, uninterrupted silver surface. When I asked about it, I was informed that falling radiation stuck to the grass and trees and raised the ambient radiation levels, and when rain would fall, it would pick up radiation from the vegetation and soil and further pollute the water, so all the trees were cut down and all the grass and soil covered with cement. The felled trees were high in radiation themselves, so they were being stored in a separate place elsewhere on the grounds. The soil had been sealed over just as it was, its undulating surface frozen in soft waves. Looking at this silver landscape spreading out in all directions, it struck me as even a bit beautiful.

The van continued its slow drive through the facility, and soon enough we were passing by the first tower, its walls and roof still blown off. There were lines of cranes surrounding it, and we could see the figures of decommissioning workers passing back and forth. From time to time we passed digital signs displaying radiation levels. The levels near the second and third towers were still high, but elsewhere, perhaps thanks to the cement covering the ground, the levels were relatively low. My only protective gear was a pair of cotton gloves they had me wear, presumably so that in the unlikely event I came in contact with radioactive material, it would stick to the gloves rather than directly to my skin. An APD—area passive dosimeter—hung around my neck.

When we returned to the large prefab building, we ate lunch in the cafeteria inside. Fifty to sixty workers were eating there with us. They were all men, many young, some with their hair modishly dyed brown or blond. The lunch menu featured five choices: two types of set meal, a rice bowl, a noodle dish, and a curry. All were just ¥380. I chose the fried chicken set meal with grated daikon and deep‑fried tofu with vegetables. It was delicious. The lunches were delivered from the Fukushima Revitalization Meal Service Center in the nearby city of Ōkuma. And in fact, we ended up touring that facility too. Unlike at the nuclear facility, there were many women working there. The facility allowed for rice to be prepared and cooked at the touch of a button, and it was able to make enough for around 3,000 meals at once. The fruit and vegetables were all Fukushima‑grown. We were told that the menu was never the same two days in a month.

*

After lunch, I took the elevator up to the top floor. Looking out from a circular window, I contemplated the rows of huge blue-and‑white tanks that stretched all the way to the sea.

This was the former site of the Forest of Wild Birds. The Tokyo Electric employee leading the tour was the one who told us about the former forest. Now, instead of trees, the site is covered with tanks of contaminated water. A single row of cherry trees remained, a line of vivid pink amid the tanks.

Hadn’t I been trying to think of “Fukushima”—this irradiated, contaminated place—as somewhere completely separate, a place with nothing in common with where I lived?

This invisible thing called “radiation.”

Hadn’t I even been comforted when I looked at the images of debris and ruin left by the disaster, as it seemed they made radiation visible, tangible?

But now, looking at Fukushima as it really was, I could no longer deny that it was utterly continuous with the world in which I made my home too.

*

During World War II, this former landscape—the Forest of Wild Birds—had been the Iwaki Airfield used by the Kumagaya Military Air Force School. In other words, it had been a training grounds for kamikaze pilots.

I wanted to know the names of the plants that used to grow here. I submitted my request and, after a bit of a wait, received my answer. Four or five years before the nuclear accident, a survey of the area had been conducted and the resulting environmental impact assessment submitted to the Ministry of the Environment.

Common fleabane, cat’s‑ear, lovegrass, cudweed, Japanese clover, pampas grass, mugwort, fever vine, gooseneck loosestrife, red pine, mountain clover, cat‑clover, horsetail, Chinese clover, sparrow’s woodrush, shady clubmoss, goldenrod, bloodgrass, wild soybean, mare’s tail, crabgrass, daisy fleabane, white clover . . .

The place I initially wrote to for information answered dismissively, writing that paperwork from that time was almost entirely lost and that now, nearly six years after the accident, people able to provide first‑hand accounts were almost unfindable, so it would take a prohibitive amount of time to conduct further research into the lost Forest of Wild Birds. So, I filed an information disclosure request directly to the Ministry of Environment myself and received the assessment results. The list of vegetation was much more detailed.

Jolcham oak, aohada, Korean hill cherry, chestnut, fir, torch azalea, Japanese sumac, Japanese snowbell, spindle tree, oriental photinia, Japanese pieris, variegated dwarf bamboo, China root, marlberry, Japanese fairybell, noble orchid, pickerel weed, water plantain, marsh dewflower, swamp millet, kasasuge grass, Maui sedge, streambank bulrush . . .

*

I go over the names one by one.

And as I do, I wonder how distinctly I can imagine each plant—each grass, each flower.

After all, spring is coming, once again.

__________________________________

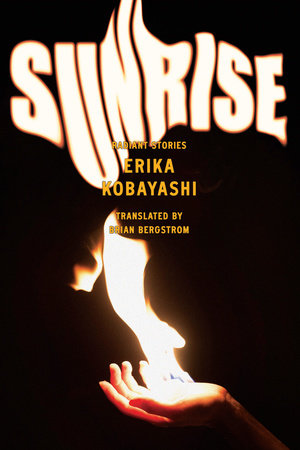

“The Forest of Wild Birds” Excerpted from Sunrise: Radiant Stories by Erika Kobayashi, translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom. Published by Astra House. Text copyright © 2023 by Erika Kobayashi. Translation copyright © 2023 by Brian Bergstrom. All rights reserved.