A woman wanted to become small. So she shrank, smaller and smaller still, until she was small enough to fit into the calyxes of the foxgloves she’d planted last winter. Her garden was now a jungle, a hemisphere, and the bees had transformed into helicopters overnight. They welcomed her as her neighbors; they offered her honey. The neighbor’s fig tree grew wild over her fence, and soon figs were falling from the branches, their purpled flesh an endless feast.

The woman was finally living a life of abundance—everything that once felt small and cosmically insignificant was now huge. Her tiny apartment, once so cramped, with the couch in the kitchen and the desk on the dresser and the bed in a loft over the desk (she never could sit up straight while answering her emails) suddenly became palatial.

Taking it all in, she realized that she missed nothing from her old life. She did not miss the drudgery, the neuroses, the loneliness, the back pain. Now look at her! She could eat and drink all she wanted from this garden and never go hungry. She could feed on nectar that tasted like marzipan apples, relaxing from the perch of her favorite foxglove all day. She could revel in the view of the garden that was now her kingdom—all that she’d planted, all that blossomed from the tiny seeds she’d once held in her hands.

Eventually she realized that someone else was now living her life. Someone else was making appointments, going to work, going on dates, going to therapy, picking up groceries, cooking, making calls for her. Someone else was watering the plants and flowers in her garden, someone with her exact physical appearance. A doppelgänger—or a replacement? At first she felt indignant, pacing around in her calyx. She was anxious that this impostor would ruin the life that was hers, the life she’d grown from the ground up. She paced and paced and waited every night for this alien version of her to come home, at first afraid that this replacement’s unknown personality would render her unrecognizable to her friends, her coworkers, and her family. Lurking beneath this fear, she was also worried that none of them would recognize her transformation at all, and her disappearance would go unnoticed.

Months went by, and she realized that this impostor was not ruining her life. In fact, this impostor was living her life much better than she had. This impostor was getting a promotion and negotiating for a salary she never would have thought to ask for. This impostor was booking a trip to Lisbon, where she’d wanted to go ever since she read Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet in college. This impostor was making new friends and reconnecting with old ones and hosting dinner parties where she successfully mixed these two groups together on the couch in the kitchen over the coffee table that doubled somehow as a dining table. This impostor was always the brightest person in the room, commanding everyone’s attention and cracking jokes that made everyone laugh. This impostor was always laughing off the “nihaos” and “konnichiwas” from men on the street because she didn’t take things so seriously. This impostor was going out until four a.m. on weekends, plopping down on the couch wearing short skirts and six-thousand-dollar leather jackets from designer brands she couldn’t afford, that she’d believed she could never pull off. This impostor had a skin-care regimen that made her glow all the time; in fact, the dark spots on her face finally vanished, her blackheads gone. This impostor found a lover who took her on ski trips and family functions on weekends. The impostor would be gone for days at a time, busy with her fulfilled life.

She’d never hosted dinner parties. She’d never taken trips. She’d never had a boyfriend. Suddenly she was getting anxious again, anxious that she had not adequately lived her life, and now she had given it up to a doppelgänger who was going to enjoy all the things she hadn’t, that she’d always wanted but had been too afraid to pursue. One day, the impostor brought home the lover, and she watched them from the perch of her petal—herself, on the bed, making love to a stranger. Hold on, though—she looked closer, and realized it wasn’t a stranger at all, but the man who, just the year before, had broken her heart. Left her by the curbside in front of a bodega, left her crying into her iced coffee, the ashes of her cigarette dusting her bare knees. The man had said he wasn’t looking for a relationship, that he didn’t like her like that, even though they’d slept together a few times already; he wanted her for sex and only sex, no, never mind, he wanted just friendship; sorry, he was sorry. This man had never taken her outside of his apartment, let alone to Thanksgiving with his family upstate. She had not met a single one of his friends.

And now there he was, with this impostor, whispering sweet words, like how he wanted to show her off to his friends, go to Europe with her, the words she had fantasized about before, uncannily—eerily—coming to life. She watched them for the rest of the night. For the first time since her transformation, she wanted to be noticed. She shouted at them, waved at them, but they could not see or hear her. She was a voyeur spying on her own existence. She began to understand that this was her worst fear coming true. That perhaps, just perhaps, something essential inside her was rotten—something primordially hers, fixed and unsalvageable. It caused people like this lover, and all her former lovers, to abandon her. But when someone else occupied her body, this didn’t happen. And just like that, she heard herself climax. A hot hiss of breath escaping from a throat that looked just like hers.

Last year when she was still seeing that man on and off, they had been careless and drunk one night, and the next morning she was so hungover that she forgot to buy Plan B. Soon after, he ghosted her. It was incremental: At first he would not respond to her texts until two or three in the morning. Then he stopped responding at all. This should have been the first sign that she was better off without him, but in those weeks of silence she felt as if her body were decomposing. It must have been the oxytocin, she rationalized—it was just chemicals tying her to this man, nothing more.

When she missed her period that month, she was still in a haze, barely eating or sleeping, and so didn’t notice at first. But after several more weeks passed, she decided to go to her gynecologist, who administered a pregnancy test. Positive. Before she imagined an actual child, she imagined the child’s potential trauma: Who would want to be born into a world where even the love between one’s parents could not exist? She thought back to her own parents, who’d barely spoken to each other for most of their marriage outside of the most essential topics, namely her; she couldn’t tell if the silence stemmed from habit or bottled-up resentment. She felt as if her own body were mocking her with its fertility. If this love was going to be barren, then why didn’t her uterus get the memo?

She went home and watered her foxgloves, her dahlias, her camellias. Then she sat on her plastic chair and wept. She suddenly craved bruised fruit. The tree from the neighbor’s yard dangled its branches over the fence, swarming with black stony figs, fat and ripe.

For the first time, she noticed the swarm of insects by the fig tree. They were tiny fig wasps, though she didn’t know it at the time—she thought they looked like gnats or mosquitoes. Concerned, she consulted her book on gardening and insects and came across the entry on fig wasps. A fig, it turns out, is not a fruit but an inflorescence, a cluster of tiny flowers that needed special wasp pollination. The pregnant female wasp finds the tiny ostiole, or hole, at the bottom of the fig and crawls inside with the intention of laying eggs. As she lays her eggs, she also pollinates the florets.

Several facts about fig wasps stunned her. The first was that, in the process of trying to squeeze through that impossibly narrow portal of the male fig, the pregnant female wasp loses her antennae and her wings. The second was that, once she crawls inside, she lays her eggs and dies. The fig’s enzymes slowly consume her, digesting her body until she becomes a part of its seeds and flesh. The third was that if the wasp climbs inside a female fig, she still attempts to pollinate it, but, unable to lay her eggs, she just dies alone.

The woman had eaten so many of these figs, and it had never occurred to her that tiny wasps could be living and dying inside them. In the summer, she would sometimes go for days without eating anything else. They reminded her also of her lover, who loved figs.

Later that night, she called him, wanting to inform him about the test. She had never called him before. When he answered, they had a casual but flirtatious conversation that gave her hope, and she could not bring herself to tell him and ruin the mood. “How have you been?” he asked, finally. “Sorry I lost touch—I’ve been so busy, you know.”

After hanging up, she made an appointment at the clinic for the following Tuesday. She thought about asking him to go with her, but she didn’t want to put pressure on him or inconvenience him. He didn’t want anything serious, he had told her; pregnancy was definitely a serious matter.

Nevertheless, when he started texting again, her body felt light, the lightest it’d been in weeks, and she felt herself sucked back into this airtight ostiole of romantic desire. They started talking more regularly and met up a few more times over the course of a few months before the incident at the curb by the bodega. By then she had already gone to the clinic, where her doctor informed her that she was seven weeks along and gave her a box containing two pills.

After taking the first pill, she bled profusely, her body cramping and clamming. She spent hours on the toilet every day, passively bleeding, and wondered if this was just all life was, all she was meant to do: Bleed, bleed, bleed. Blood would flow out of her until she ran out. No pads, tampons, or menstrual cups stanched the flow. A gloom, like a decomposing wasp, crawled inside of her, and the rot felt familiar, the rot felt true. She imagined herself suspended in a fig’s red flesh, bleeding all over its flowers.

The next evening, the waves of nausea passed, and she felt enough strength to host him again. He came over, and as usual she fed him the figs from her neighbor’s tree. His favorite thing about figs, he told her, was that they had no pits. How easy it was to just swallow them whole.

They sat together in silence, watching the sunset from her street-level window. When he reached for her, a small noise escaped her throat, a yelp. She turned her body away from him, suddenly protective of it. The nausea and lightheadedness returned, and she made up an excuse to go to the bathroom and vomit.

He didn’t ask her what was wrong. Instead, he turned on the television and flipped through the channels, snacking on her chips, pretending nothing was happening. She actually felt relieved at his lack of curiosity, because she wouldn’t know how to explain without telling him the truth. Finding nothing of interest on TV, he left shortly after.

Emerging from the bathroom, she threw out the empty bag of chips and the fig stems he left in the bowl, opened the door to the garden, and pulled up a chair outside. The sun had not fully set yet—the summer sky was delirious with pink streaks, like little scratches on skin. “Wow,” she marveled, at nothing in particular. She wiped her mouth, which had gone sour, feeling small, so very small. If only I were actually small, she thought. Perhaps it would make my problems go away.

A movement in the fig tree startled her. A few roof tiles scuttled down from the eaves, and she looked up, but there was nothing. Figs fell, too, as the branches of the tree trembled. Then in front of her, to her amazement, appeared a tawny fox with flaxseed-yellow eyes. It was crouching in the long stalks of the foxgloves. She looked around for holes or burrows but could not find a portal through which this fox had entered. In the dusk, which seemed yellow now, too, the creature peered at her, regarding her with a mixture of trepidation and interest. She’d heard of foxes as omens before, usually auspicious. She beckoned it with a fig in her palm, but its wet nose did not stir. Soon the last ray of light shivered away, and the eyes of the fox lingered and winked. And then, before she was ready, it scuttled off into the night like one of her lovers.

Spring soon molted into summer, and she grew bored of her smallness. Around this time, the impostor was on her vacation to Europe. Imagining the terra-cotta rooftops of that city she’d never seen, Lisbon, and the deep blue of the Tagus River, she felt an intense longing.

The woman didn’t want to be small anymore. She’d grown bored of the smell of flowers and the taste of nectar and honey and figs. The view from the foxglove began to madden her, fill her with despair. She watched a man next door pan-frying a branzino, and the smell of butter sizzling on skin made her desperately crave human pleasures again. She watched the fig tree and the female wasps kept digging and dying, digging and dying. She witnessed one female after another attempt to wrangle its body through the tiny hole at the bottoms of the figs. Sawed off, like cellophane or parachutes, pieces of wings fell from the figs.

Then she noticed that there were new tenants living in the figs. Newborn female wasps were leaving—the daughters of the wasps that had decomposed had hatched inside the figs, orphaned from birth. Now they were nymphs, already gnawing their way out, embarking on the journey of finding another fig tree. The skin of the figs on the branches gave way to flesh and pulp, and the newly minted female nymphs were liberated.

That’s when the woman considered: Perhaps she, too, could leave? Perhaps she could also journey to an unknown fig tree, escape this life once and for all. By this point, she had forged an uneasy communion with the bees and other insects that frequented this garden. She could ask them to relay her message to the fig queen, who had just emerged from the plumpest fig on the farthest limb of the branch.

Word got back that the queen had agreed. The woman found herself swooning: Oh! Emerging from her fig womb, the queen was unrivaled in her majesty, wearing a gown of pollen that resembled intricate lace. The queen’s brown body was decked in a sleek armor resembling patent leather, and her silky wings fanned out, a holographic vision catching every errant ray.

Soon the queen descended on her foxglove, and the woman climbed on, gripping her thorax. The queen’s body was sticky with nectar, and the pollen felt fluffy, like hairy flesh—the woman grew drowsy, but she didn’t want to sleep. They were flying up in the air, and she saw her garden grow smaller and smaller, and yet it was entirely unlike being on a plane—no glass or metal separated her from the wind, which could not hurt her. From her vantage point, she saw the corner store. She saw her neighbors sitting on the stoop eating their figs. She saw the park where she used to lie out on the grassy knoll alone. She saw the botanical garden where the peonies and wisteria still budded, their petals all sprayed with rat repellent. She saw the statue of the weeping girl near the algae-green pond. She saw the fish market, with its display of striped sea bass, golden pompano, red snapper. She saw the bodega where she got dumped, and it looked marvelous with its display of bountiful melons. She even saw, for a tiny millisecond, a fox flashing in the graveyard where she sometimes walked her bike.

She was amazed. The journey to another fig tree felt like the farthest she’d ever traveled in her life, even though it had to be no more than a few hundred yards. When they eventually reached their destination, she almost threw up, her wonder mutating into dread. As she was dropped onto the branch of a new tree, she pleaded to the queen not to let her go. She didn’t want Her Majesty to die so young. When she saw that the ostiole on one of the new figs was already open, she screamed at the queen not to rip off her wings. Instead of waiting on the branch, witnessing, she found herself running, climbing over onto the queen’s antenna, launching herself into the red fragrant flesh of the fig. She would use her own body as a shield to save the queen. She would pollinate the fig herself.

As if the fig had heard her, the hole closed up once she climbed inside. Whole gardens of florets, pale and vulnerable, waited for her. In this red fig womb, suddenly she was more exhausted than she had been all her life. Too tired to remember anything about herself, too tired to save herself from being digested. Deeper and deeper she crawled into the fig, following its perfumed trail. It turned out that the fig, ever the hospitable host, had been expecting her, had already made a bed for her. On all fours, she crept as far as she could, the pollen falling off her, and curled into a ball on the soft pink bed.

In the red fig womb, she became an amorphous thing, a zygote, a fetus; she was breaking down. She was in a fugue state, where life and death had no language, the ending was a beginning was an ending, and she felt her own nonexistence like a warm airless room, a sauna. Her naked flesh in that air of fever vapor. Her lovely bloodless flesh in a sauna and then a clinic room, bent against the metal speculum. Her bathroom where she took that pill. The blood on the toilet seat, on the bathroom floor, all congealing. In her bleeding, she had spared someone from existence. She thought of her mother, who mentioned once offhandedly that she had gone through three abortions before finally choosing to have her. The one-child policy in China made her mother anxious about her body, its fickle patterns of creation. In the end, she finally had her daughter, and the trouble with daughters was that they, too, would eventually bleed. Without bleeding, who was she? Who was her mother?

In the kingdom of fig wasps, there were no singular monarchies. Every female wasp who made the journey of breaking her body was a queen—their coronation was death and decomposition. They were all mothers, and just like her, they were no mothers. The impostor living her life could have been any number of things: a demon, a fox spirit, a ghost. But perhaps it was just another version of herself, a self that was not broken, a self that did not believe she was broken—perhaps this woman had been sleeping inside her, underneath her pain, all this time. But instead of recognizing her, she’d called her an impostor. A doppelgänger, instead of something that she herself had dreamed, manifested, wished to life. In her fig womb, the city of Lisbon materialized. A balmy breeze blew through the open door leading to the balcony of the inn. The suitcases were packed. A note taped on top. Goodbye. We’ll meet again soon.

Even if it meant death, the woman couldn’t think of a better way to go—the juices and fragrance of inflorescence lulled her, and somehow she heard music. When she was ready to die, she fell asleep.

She opened her eyes, and she was back in her bed, covered in sweat. The alarm rang next to her. With wonder and relief, she felt a foreign yet familiar heaviness in each limb—how much effort was required just to arch the spine, to reach her arm out and hit snooze! The unsung effort the neck expended just to hold her head up! Every part of her, from her soles to her scalp, felt sore with muscle and bone. Even so, she had a newfound respect for this body, its dance with gravity. An hour went by before she could will herself to get up.

She cautiously stepped onto her kitchen tile, afraid she would crack it with the weight of her foot. Then she walked carefully outside onto her patio, then her garden. She watered her foxgloves, her oxalis, her camellias. She picked up some figs that had fallen onto the ground.

Then she opened her laptop and checked her inbox and noticed it was full of emails from people she didn’t know. Strangers, new friends, some whose names she recognized from the dinner parties. And many, many emails from that ex. His latest email was sent at 11:12 a.m. “Where are you??” was the subject line. The message was blank. She rolled her eyes. Oh, so now he was looking for her? She clicked through the rest of the increasingly frantic emails he had sent, and gathered that she—no, her impostor—had been in Lisbon with him and disappeared from their room that morning while he was out for a run. She checked the inbox history: according to the receipts from Tripadvisor, they had booked a terraced hotel room with a balcony overlooking the river. It dawned on her that now that she was back in her full-sized body, the impostor might have vanished. She wondered if she should reply, if she should book a flight. She could arrive at their hotel by the next bright morning, and he would be so relieved to see her that he wouldn’t even notice she was different.

It had been her dream—to travel with this man. It had been her dream that he’d come back to her. For so many nights in the past year, the moment she closed her eyes she relived the way he touched her, where he put his hands, what he whispered as she drifted toward sleep—surprisingly tender things that had confused her; she relived the nightmare of iced coffee and cigarettes and the bodega. Sometimes she imagined an alternate reality where she chose not to take the pill. What then? Perhaps they would have been a family. She knew full well the impossibility of this fantasy, and yet there was safety in that certainty, in knowing it would never happen.

But that moment had passed, and now she found herself feeling something she didn’t expect: amusement, even satisfaction, that she was not going to Lisbon, not for this man, no. She was amused that he was so confused by her whereabouts, that he probably at the moment felt abandoned, disoriented in a foreign country and suddenly alone. But she owed him no explanations about where or who she was. Today, tomorrow, she would go to the botanical garden, a ten-minute walk, smell the rat-repellent fragrance of wisteria and peonies, record their names. She would revisit the places she saw from the air on her journey—the neighbor’s stoop, the corner store, the pond, the weeping girl, the fish market, the graveyard, and maybe even the bodega. If she saw the fox, she would hand it a fig.

Before she left her apartment, she gathered and washed some in a bowl. Then she drew a bath and soaked for a while, eating the figs one by one, swallowing even the hard stems. The steam and water loosened her tense muscles, and her aches started to vanish. She scrubbed herself until the dead skin sloughed off, and underneath, she was new.

__________________________________

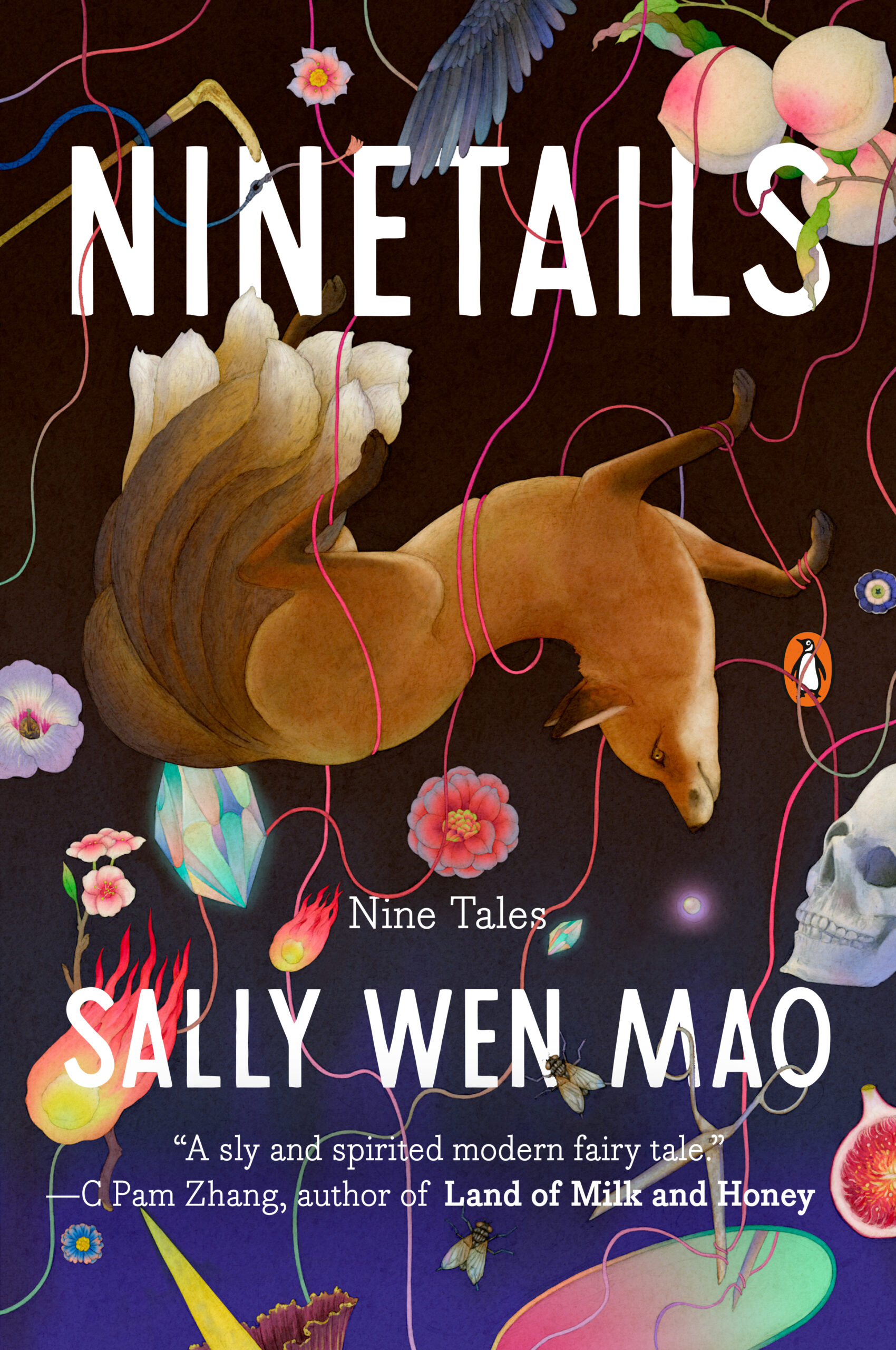

Excerpted from Nine Tales by Sally Wen Mao. Copyright © 2024 by Sally Wen Mao. Published by arrangement with Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.