The Female Philosophers Unjustly Excluded from the Canon

Regan Penaluna on Christine de Pizan, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Anna Julia Cooper, and More

Most of the years I spent wading through the Great Books of philosophy, I came to learn that women were not only missing from the canon but degraded by it. If only I’d known about the many beautiful and forgotten books from long ago by women or in their defense. Then, I may have realized that some of my doubts and concerns were not unique but shared by other women since the dawn of philosophy, and perhaps I wouldn’t have struggled so much.

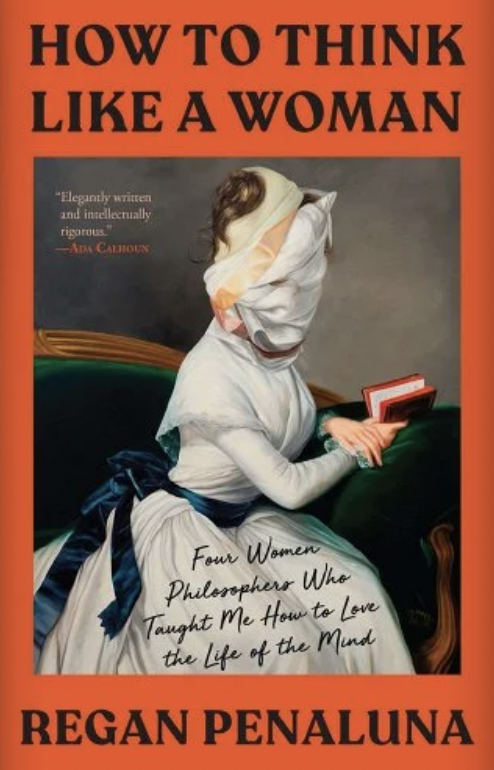

I wrote my book How to Think Like a Woman to tell the story about how I came across these long-forgotten women philosophers, and how their insights helped me navigate a divorce, a cross-country move, a new job, and motherhood. I also wrote it to share their stories and ideas, to catalog them for others, to make the case that they deserve a wider audience and a lasting place in our collective memory.

In my book, I join the chorus of feminists exposing the ways that men’s experience has often stood in for the universal human experience and demanding that women’s experiences be treated with equal attention and care. To make this case in my book, I focus on a few core texts, but here are some additional inspiring and accessible works by women that I can’t stop thinking about and now hopefully you won’t either.

*

Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies

In this medieval work, a woman named Christine falls into depression after learning about the countless ways male writers throughout history have disparaged women. Then three ghosts appear to her with a task: Christine will write a catalog of great women from history, whose biographies they will dictate to her. The ghosts promise this will lift her spirits and those of similarly down-trodden women who will come across this soon-to-be book.

Originally published in 1405 as an illuminated manuscript in medieval vernacular French, The Book of the City of Ladies describes a metaphorical city built from short, often quirky, biographies of women real and fabled from the ancient past up through the books’ completion (Joan of Arc, Pizan’s contemporary, has a cameo).

Pizan takes inspiration from Boethius’ On the Consolations of Philosophy, but unlike him, she is speaking directly to women. Over six-hundred centuries later, her book still feels relevant, which was Christine’s hope and her dedication attests: “To those of you who have died, to those of you who are living, and to those of you who are to come.”

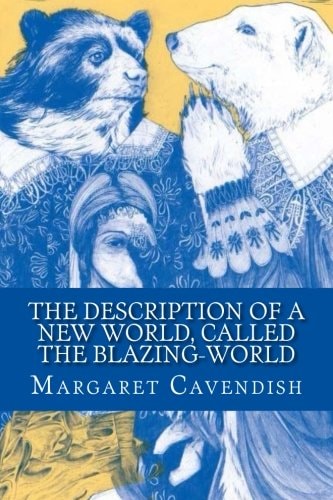

Margaret Cavendish, The Blazing World

This is one of the funniest books I’ve read. Written in 1666, it tells the tale of Margaret who visits another planet where she is made an empress, something that the author humorously confesses in the dedication as a great wish of hers. Yet, because she was born a woman there is no hope she could rise to rule in this life. So she invents a fictional world where she does.

Once she arrives at this new land, she is crowned “Empress” and encounters all sorts of strange creatures who treat her with dignity and respect, something she doesn’t experience much on Earth where men show little to no interest in ambitious, intelligent women. Now that she has a sympathetic audience, she takes the opportunity to share her thoughts on natural philosophy (ideas that Cavendish developed against those of the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, but who ignored them).

Although this work is written in seventeenth-century English prose, Cavendish still makes me howl with laughter.

Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz, Selected Works

Born in a small Mexican village in 1648, Juana Inés de la Cruz was a child prodigy who went on to live in the Spanish court in Mexico City. She eventually joined a convent, probably to avoid marriage and secure herself time to study and to write.

She deeply appreciated the work of René Descartes, and shares his commitment to reason and his skepticism for authority, which infuse her writings. She became a celebrated dramatist and poet, but after her death she was forgotten for centuries until more recently.

Here is a stanza from one of my favorite poems: “Silly, you men so very adept / at wrongly faulting womankind, / not seeing you’re alone to blame / for faults you plant in woman’s mind.”

Mary Wollstonecraft, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark

Wollstonecraft is known for her foundational feminist text Vindication, but the mother of Mary Shelley also had a sophisticated literary sensibility. She wrote novels, critical reviews, and this gorgeous collection of letters to an unnamed lover that’s part travelogue and part memoir.

Two conflicting impulses drive her observations: a sense of wonderment and wish to test scientific and philosophical theories on her new experiences, and a sense of despair upon the growing realization that her lover and father to her first child no longer wanted her. In one such missive to him, she writes: “Every cloud that flitted on the horizon was hailed as a liberator, till approaching nearer, like most of the prospects sketched by hope, it dissolved under the eye into disappointment.”

This is Wollstonecraft at her most vulnerable and exquisite. Her future husband, William Godwin, said he fell in love with her after reading it.

Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South from a Black Woman from the South.

Why isn’t Cooper in the feminist canon, along with Mary Wollstonecraft and Simone de Beauvoir? wonders a biographer. After reading this collection of essays by Cooper published in 1892, I had similar thoughts. She should be.

Cooper, a Black American who earned her PhD from the Sorbonne by comparing the French attitude toward slavery during the French and Haitian revolutions, devotes this work primarily to the treatment of Black women in the U.S. She touches on themes such as the importance of educating Black women so they can achieve economic freedom and self-determination, and the blinkered views of white feminists who advocate on behalf of “women” but rarely have all women in mind.

In many ways, Cooper seems well ahead of her time. She adhered to the idea that knowledge is embodied, that is, our race, class, politics and many other aspects of our being, shape how we think and what we value. She reminds us that this holds even in the most abstract spheres, and that we are morally responsible for others no matter how scientific or philosophical our thinking.

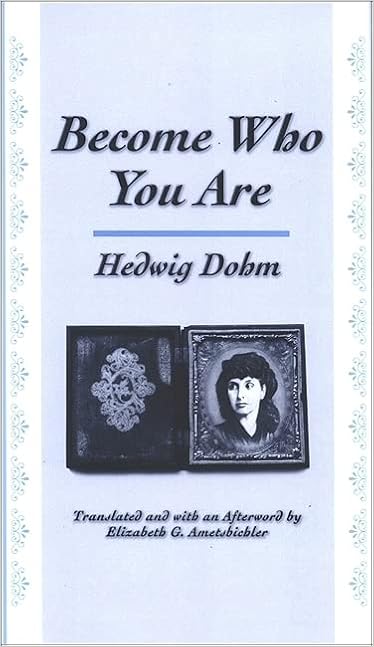

Hedwig Dohm, Become Who You Are (trans. Elizabeth Ametsbichler)

In this slim German novel from 1894, a sixty-year-old woman in a sanitarium hands her private journal to a doctor flummoxed by her case. He sees no reason for her to be unhappy: she was married with children. But her journal reveals more. Now that her daughters are grown and her husband is dead, the protagonist realizes her empty nest reflects an emptiness inside herself: “I am no one.”

An existential crisis ensues. “Why did I have to live as I have lived? Because I am a woman and because it stands written on ancient bronze tablets of law how a woman ought to live? But the text is erroneous; it is erroneous!”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that the protagonist describes the best years of her life as those spent in the sanitarium, where at least people are curious about her inner life. It’s a dark, poignant suggestion, and Dohm is punching high here. She’s responding directly to Nietzsche and Freud, whose theories had little to say about the plight of women past childbearing years.

___________________________

How to Think Like a Woman, by Regan Penaluna, is available from Grove Atlantic.

Regan Penaluna

Regan Penaluna is a writer and journalist based in Brooklyn. Previously, she was an editor at Nautilus magazine and Guernica magazine, where she wrote and edited long-form stories and interviews. Her writing has also appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Philosophy Now, and the Philosophers' Magazine. Penaluna has a PhD in philosophy from Boston University and a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University. She is the author of How to Think Like a Woman.