The Eye of the Storm: Karie Fugett on What Draws Us to Danger in Our Relationships

"I couldn’t have known then that this was only the beginning. Soon, I would carry so much more than I ever asked to hold."

I wake up on a blow-up mattress next to a mountain of beer boxes with a pistol under my pillow. I’d noticed its hard edges on my cheek, felt around, and paused when my fingertips touched cool metal. I pull it out and hold it flat in my hands, stare at its angles and curves, consider the desolation of the barrel, trying to remember how the hell it got there. Cleve is already awake and pulling a yellow-and-blue-striped polo shirt over his head.

“Uh…what is this?” I ask.

He chuckles and sits down on the edge of the mattress. With pops and squeaks, it lifts my body and rolls me toward him.

“Don’t worry about that,” he says. He picks up a pair of camo-print cargo shorts that’d been crumpled on the floor next to the mattress, pulls them over his legs, and stands once they’re at his thighs. My mind is somewhere else, struggling to piece together the night before. The sound of Cleve’s zipper pulls me out of a trance. “I put it there.”

It has always made more sense to me that the person whose life flashes before their eyes is the one about to take the life of someone else.

He explains that the night before, he’d found Fowler, his nineteen-year-old Marine Corps buddy, frantic and sobbing with both arms extended, the pistol squeezed between his sweaty, trembling hands and pointed toward his wife. Earlier that night, Fowler’d found a love letter in the hidden compartment of a wooden box his wife kept in her nightstand. It was from another Marine in their unit. One of his best friends. “Our baby’s in the other room, you fucking psycho!” she had screamed, but Fowler remained eerily silent, motionless. I imagine his face distorted by the puffy wetness of his crying, imagine his wife regretting saying those words the moment they fell from her mouth. Did she drop to her knees and beg for forgiveness, willing to do anything to save her own life? I wonder what I would do if I were looking down the barrel of a gun. They say that when someone is about to die, they see a montage of their life leading up to that point. Movies depict the moment before death as a reel of happy memories. Birthdays, graduations, first kisses—one after another after another. But when I imagine this young woman, her baby in the room on the other side of the wall behind her, I know she was thinking about her future, all the things she would miss out on, her parentless child. Cleve, a peacemaker among his friends, convinced his buddy not to shoot.

“Hey, man. This isn’t you,” I imagine him saying with both hands in the air as he slowly moves toward his friend. “Look me in the eyes. I love you, man. Put the gun down. I got you.”

I wonder how much Fowler resisted Cleve’s urging. Did he hand the gun over right then, or did he tighten his finger around the trigger? It has always made more sense to me that the person whose life flashes before their eyes is the one about to take the life of someone else: all those moments that chipped away at their humanity until, finally, they break, leaving an unrecognizable version of themselves looking over the edge of the abyss, unable to conceive of any other option but to kill. Fowler must have thought of something worth not going to jail for, because he lowered the gun and handed it to Cleve. I’m sure Cleve hugged him. Cleve was a huge guy, and when his arms wrapped around you, you were cocooned, safe, and, for a moment, protected from the rest of this terrible world.

I’d been so drunk, I had already fallen asleep when all of this went down. I missed the whole thing.

*

I’d flown into Jacksonville to visit Cleve the night before. I was still wearing my navy blue flight attendant uniform, with my long brown hair twisted into a bun, tiny gold-painted wings that said US Airways pinned to my chest.

When I turned the corner into Arrivals, Cleve stood next to the luggage carousel, his smile broad and his arms open. I dropped my suitcase and bounded toward him, flinging myself into his arms. Wanting to remember his scent, I pressed my cheek against his chest and inhaled: spearmint and spicy-sweet deodorant.

“I missed you, Fugett,” he said with an Alabama drawl. I nodded to say Me too, and squeezed him tighter.

“You’re gorgeous in that fuckin’ uniform,” he said, and we kissed.

I thought: This is our second first kiss. Our first first kiss had happened years ago when we were kids—all lanky limbs and fickle hearts— blissfully unaware that it marked the first day of the rest of our life together. Or that I would end up being the love of his short life.

Cleve retrieved my suitcase, grabbed my hand, and led me outside. He loaded my bag into the trunk of his white Mustang, and I slid into the passenger seat.

“Ready to meet these crazy bastards?” he asked as he started the car. The engine growled to life as I buckled my seatbelt and pulled down the sun visor to check my appearance in its mirror. My eyes—pale blue with prominent limbal rings—sparkled in the visor’s buttery light. They were the one physical feature I’d always been confident in—the one thing I could count on being complimented on. Mascara had smudged below my right eye. I licked my index finger and wiped it away, then looked at Cleve. “Yep.”

Jacksonville was a man’s world, the whole damn town a bachelor pad. The main drag, which led to Camp Lejeune, wasn’t much more than asphalt and spindly pines. The rest was car lots, strip clubs and tattoo parlors, chain restaurants, and a sad excuse for a mall. Young men with matching crew cuts roamed in packs on the sides of the road; colorful hot rods purchased with deployment money revved at red lights; and in the median of Western Boulevard, the Jacksonville Ninja, an anonymous man who felt as natural to the place as the pines, practiced his finest karate moves with a boom box on his shoulder. Background noise was artillery rounds and low-flying aircraft, both so loud they often set off car alarms. Few people were local; nearly all of Jacksonville’s residents were transplants lured there by the Marine Corps with its fancy uniforms, cool guns, and promises of bonus money, healthcare, and retirement.

In a town full of bored young men, there was no shortage of house parties. Cleve took me to one straight from the airport, stopping only for a bag of McDonald’s double cheeseburgers and a tank of gas. He warned me on the way, “These guys get pretty wild.”

I rolled my eyes and laughed. Not even six months ago, I’d been living in Tampa, a place known for its nightlife; I’d survived plenty of parties like this. In Tampa I’d worked at a popular alehouse, which meant sleeping in, working late, then going to whatever rager was happening that night. House parties were often held at pastel-colored, palm-tree-lined mansions. Kids rolled blunts the size of cigars, pissed in the pool, streaked through the house, tripped, snorted, and fucked in the back rooms.

By nature, I was shy, but I’d grown to enjoy proximity to chaos and recklessness, the thrill of trying mysterious new things and surrounding myself with extroverted people. A sort of high came with the risk involved at parties: a fight could break out; someone was probably cheating somewhere; the neighbors could call the cops at any moment. I found it much more interesting than my life had been when I was a kid, with my ten o’clock curfew and Sunday morning church services. Besides, it was easy to fly under the radar, everyone too sloshed to judge me sitting in the corner, petting the dog, and observing the circus around me.

I shrugged. “Tampa was pretty wild. I’m sure I’ll be fine.”

“Well, Hamilton and his wife are swingers,” Cleve said. “If they go in the back room with anyone, it’s probably best you don’t go back there. Sometimes they snort lines and shit, too, so…”

“Don’t worry about me,” I said. I reached for Cleve’s hand and pulled it to my mouth for a kiss. “I’m not the innocent Foley girl you met in eighth grade.”

I’d grown to enjoy proximity to chaos and recklessness, the thrill of trying mysterious new things and surrounding myself with extroverted people.

“Well, that’s for damn sure,” he said. He winked, let go of my hand, and squeezed my boob.

When we arrived, a man wearing nothing but socks stood on a coffee table, swinging his dick in circles, screaming Wooo! over and over between glugs of his beer. Behind him, empty cases of Bud Light were stacked against the wall up to the ceiling. The air smelled like stale cigarettes and broccoli, and to the left of me, a man with Brillo-y pink hair sprawled across a tattered green couch, his head and one of his arms hanging off the edge.

“He took a Xanny bar,” the naked guy said. “He’s fine. Woo!”

Cleve made his rounds, saying hi to all his friends. I followed behind, holding on to the back pocket of his jeans. Five people in their underwear sat on the back porch playing strip poker. It was mid-November and cold enough that you could see your breath. I thought they were crazy. A shirtless guy introduced himself by telling me he had a third nipple. “See?” he said, pointing to a spot in the center of his rib cage. It looked like the chicken pox scar I have on my chest, powder pink and slightly raised. I wondered for a second if my mom had lied to me and if I actually had three nipples, too.

“I am way too sober for this shit,” I said, and Cleve led me to the beer. I drank as much as it took for my anxiety to slip away, for a messy confidence to take its place. I don’t remember much else. The next morning, I woke up with the gun under my pillow.

*

“Just put it in your purse,” Cleve says as we get dressed. “There aren’t any bullets in it.”

Gripping the gun cautiously, I push some tampons aside and cram the thing in my purse, noting how strange it looks next to my pink wallet. Being in possession of something that holds so much power scares me.

I’d never held a pistol before, only a shotgun once when I was nine. Dad had woken me in the wee hours of the morning and snuck me out of my room to drive me to the edge of my aunt’s farm in Elberta, Alabama. We sat in a tree stand for hours before we spotted a doe. Dad placed the gun in my arms and positioned it toward her.

“Look through here,” he said. “Do you see it?” “Yeah.”

The creature was apparition-like, peacefully grazing on soybeans in the dawn light.

“Put your finger on the trigger here,” Dad said. He placed his index finger over mine. “Ready?”

I swallowed to loosen the knot in my throat. He pressed my finger, and the gun exploded, the recoil strong enough to leave a sore spot on my puny shoulder. The doe disappeared. We assumed I’d missed. But then I overheard my dad talking to my uncle about it. They’d found the deer dead in the woods not far from where I’d shot it. It was pregnant. I vowed I’d never shoot a gun again. Eleven years later, I am struck by the heaviness of the pistol in my purse. I don’t trust that it doesn’t have bullets, that it won’t go off by accident. I don’t want to look like a wuss, though, so I carry it anyway. I couldn’t have known then that this was only the beginning. Soon, I would carry so much more than I ever asked to hold.

__________________________________

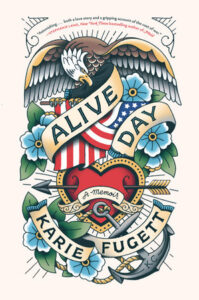

Alive Day by Karie Fugett is available from The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Karie Fugett

Karie Fugett holds a BA from the University of South Alabama and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Oregon State University. Alive Day is her first book.