The Excruciating Decision to

End a Cat’s Life

Martha Cooley on Bohumil Hrabal, Stevie Smith, and the

Death of Her Cat Zora

This essay was written in early April 2021.

I write this to prepare myself for an act I will commit in a few weeks.

The object of the act is my cat, Zora, a 19-year-old who has lived with me since roughly two months after her birth. She came from a pitch-dark cellar where her mother had abandoned her. The cellar’s owner wanted the kitten to disappear; no rescuers materialized, at which point the owner really wanted her to disappear. Hearing about this situation from a friend, I impulsively said I’d provide a home for the cat. Zora reacted to her relocation with bites and scratches, but I treated her worms and mange and got her a little cat-bed and a few toys, and gradually she calmed down. Thus began our long association, during which she has periodically been cared for by apartment-sitters but has never left her home.

In a couple of months, my husband and I will leave the United States and move to Italy. At present Zora is not at the edge of death, though she has kidney disease, defecates outside the litter box, must eat small portions multiple times daily or else vomit, and is entirely deaf. She sleeps a great deal. Despite a mild limp, she can still jump on the sofa or the bed so as to curl up in her chosen spots. She exposes her belly to me—something she never did til recently—and likes having the underside of her jaw rubbed quite hard. Her purring is sonorous and relaxed. She sometimes wheezes in her sleep, and I believe she dreams, for she twitches and stretches as if in response to dramas only she can attend. They’re mostly tranquil, with occasional bright flashes—memories, I imagine, of catching mice, which she did when we had an infestation a few months ago, dispatching five mice in as many days. Quite a feat for an old maid.

We’ll have to start packing up our apartment soon. Zora knows what a suitcase means, what boxes are for. In any case she won’t be going with us. If the sheer strenuousness of traveling in the belly of a jet wouldn’t do her in, a transatlantic flight would give her either a heart attack or a nervous breakdown. So would dislodging her from her home. The last time Zora had to move (when my husband and I changed apartments six years ago), she crawled inside her covered litter box and refused to emerge for two days, during which she didn’t eat, drink, pee, or poop. Subjecting her to the disorder of packing, which she knows perfectly well bodes a departure, seems pointlessly cruel. And who would take in an ancient, not-that-far-from-death cat with her needs?

*

In the 1980s, the Czech author Bohumil Hrabal’s numerous cats sat around watching him write, “lulled by the clacking” of his typewriter. He’d begun composing his memoir All My Cats in his country cottage outside Prague.

The cats eagerly awaited the writer’s regular arrivals, bestowing affection upon him lavishly. When he gazed at one in particular, his favorite, “she’d go all soft and [he]’d have to pick her up and for a moment [h]’d feel her go limp from the surge of feeling that flowed from [him] to her and back again…” What would befall these creatures, the writer worried, if something were to happen to him? Who would feed these stray cats?

Nobody, Hrabal concluded, could “kill a cat, let alone a person, with impunity, nor can one with impunity expel a person, let alone drive away a cat, without consequences.”

The cats thrived. But then they started multiplying, and as time passed the situation grew untenable for Hrabal and his wife. Something would have to be done, he realized with dread—and “it fell to [him], who loved cats, to be the one to do it”: to get rid of a handful of the youngest felines. “I stroked the kittens,” he wrote, “but was trembling with dread because the longer I allowed my hand to linger, the more I knew that this was the hand that would have to randomly choose some of [them] and usher them out of this world.”

In a near-delirious state, he finally did so—killing six kittens by putting them in an old mail sack and bashing it repeatedly against a tree, then finishing off the task with an ax. Although he realized he’d “failed to weigh the consequences of what [he] had brought upon [him]self,” shortly thereafter Hrabal ended up killing his favorite cat, Blackie, when she became ill, holding her so tightly to contain her convulsions that he snapped her neck. To make matters worse, Blackie’s son, a tomcat named Renda, was returned to Hrabal by neighbors on whom he’d tried in vain to fob him off. Gazing implacably at Hrabal, Renda refused to forgive the writer for having abandoned him, or so it struck Hrabal. Thus, the writer’s guilt increased: he’d repudiated an animal’s unconditional love.

For nearly a year, awash in self-loathing, Hrabal awakened each morning drenched in sweat, wondering if he’d end up hanging himself. Yet, he confessed, “[t]here were still things I wanted to write, even if it were only this indictment about how I betrayed my tomcat, Renda, just as I had his mother.” Each anguish-filled day, he considered “what kind of breakdown might [he] have suffered had [he] killed a human being.” Thus surfaced an unavoidable moral question: how not to equate cruelty toward animals with cruelty toward people? What kind of a person was he, anyhow? Nobody, Hrabal concluded, could “kill a cat, let alone a person, with impunity, nor can one with impunity expel a person, let alone drive away a cat, without consequences.” There’d have to be something to pay for what he’d done.

Nonetheless, the writer continued to spend time at his cottage, and inevitably, another round of cats entered his life. He became enamored of a black kitten, hoping this feline would free him from his guilt. But its mother began fighting noisily with another mother-cat, which made it hard for Hrabal to write; and one day, watching helplessly as the two cat-mothers terrorized a baby rabbit, Hrabal realized he felt very much like the rabbit: “[I]n my life I had often been accused of things I had not done, accused merely because I existed, because I liked to laugh, and people never forgave me for it, just as they never forgave me, condemned me, in fact, for being in constant good health, for being cheerful…and taking life as it comes.”

The rabbit soon died of fright, which led the writer to indict the mother-cats for judging the rabbit guilty “of a crime it had not committed.” To make things worse, the two mother-cats then started fighting with their own broods. This pushed Hrabal to the brink. Before long, he’d killed one of the mothers—an act that did nothing to relieve his agitation: “[N]ot even the image of how that cat had stood in judgment over the innocent little rabbit and caused it to die of fright could calm me.” He’d become, he realized, a man completely out of control, unable to stop thinking about “how far he’d sunk into a hell of his own making”—a hell “prepared for him by the cats he loved and felt compelled to murder.” The conclusion of All My Cats, whose final pages are a dark bedazzlement, drives the reader as well as the author into “the very heart of incalculable consequences.” Hrabal’s conscience has been permanently riven.

*

In “Cats in Colour,” an essay introducing a book of photographs of cats, the English poet Stevie Smith is skeptical about projecting human feelings onto felines.

“It is we who have…thrown our own human love upon them and with it our own egocentricity and ambition,” she writes. “[W]e make up stories about them, give our own feelings and thoughts to our poor pets, and then turn in disgust, if they catch, as they do sometimes, something of our own fevers and unquietness.” Cats’ lives, the poet asserts, are ineffable, “hidden from us and protected by darkness… [T]hey belong to another world, and from that world and its strange obediences no human being can steal them away. It is a thought that cheers one up.”

So it does. Yet as Smith also observes, cats “for all their appearance of indifference and self-sufficiency are nervous creatures… [W]e have given them reason to be, not only by cruelty but by our love too, that presses upon them. They have not been able to be entirely indifferent to this and untouched by it.” What’s more, they’re pressed upon by our narrative impulses. We treat cats as blank pages on which we can write whatever story we like—which is fine, says Smith, if one thing remains clear: “what you write throws no light on puss but only on yourself.”

Smith is nuanced in her assessment of this dynamic. What she calls the Cat-Fact—a cat’s “limitless inability to meet us on human ground”—is useful to us, she says, for when we find ourselves “sick of the nerves and whining of our own human situation vis-à-vis our fellow mortals,” the Cat-Fact lets us scrawl on feline blank pages “our own grievance, bad temper and unhappiness, and scrawl also, of course, the desired sweet responses to these uncomfortable feelings.”

Smith gets at some of what Hrabal exposed with such unflinching candor in his memoir, namely, human beings’ always latent cruelty toward vulnerable felines. “I like the feel of a soft fat kitchen cat that folds boneless in one’s arms,” writes Smith. “I could crush a fine cat.” Not to worry, she adds, as if to elude the lure: “The docile pet will turn if the pressure annoys him, out come the beautiful claws; our pet is not unarmed.” Certainly not. But when it comes to the use of those claws, we must inquire about motive, which complicates things. Gazing into the eyes of a pacing tiger at a zoo, Smith finds herself “reading cruelty there and great coldness.” Then she questions her reading: “Cruelty?…is not this also a romanticism? To be cruel one must be self-conscious. Animals cannot be cruel, but [the tiger] was I think hungry.”

Was the cat Hrabal watched as it toyed with the baby rabbit hungry or cruel? That cat didn’t eat its prey after bringing about its death. So what exactly, by its own lights, was the cat doing? “To invent stories about cats, to put words in their mouths”—no harm done, says Smith. But only “so long as we do not pretend they are not fancies.”

*

It is no fancy, my upcoming date with Zora at the office of the veterinarian.

I am doing this the easy way, one might say. I will not be putting my cat in a bag, then banging that bag against the trunk of a tree. I tell myself that Hrabal’s kittens probably didn’t suffer much after the initial stunning blows; the whole thing was probably over in a minute or so. For the writer, however, that must’ve been a very long minute. It saddled him with a guilt so massive and incessant that it prompted a book-length meditation on the moral conundrums he couldn’t pretend to evade, acts he’d committed that he couldn’t un-see, cruelties he couldn’t undo.

I cannot imagine myself thrashing a bag of kittens. A needleful of clear fluid will end my cat’s life in a few seconds. But here I am, trying to make a story I can believe in about what I’ll soon do. I will, after all, be deceiving my cat into thinking we are going for a ride in a car, when in fact we’ll be going to her death. And even if this deceit is a fancy of mine (after all, Zora won’t know I’ve deceived her), it’s not something I can set aside.

For the fact is that my cat has never deceived me. Tricks, yes: when young, Zora would stalk me playfully, dashing out from a corner to nip at my ankles and scare the bejesus out of me. And on occasion she’s bitten me, not too hard but earnestly, to my unhappy surprise. But that’s happened only when I’ve frightened her or been pushier than she could tolerate. Sometimes, too, she’s behaved like a sore loser: if we roughhouse and I “win,” she’s not been above taking a swipe or nip at me, to show she’s regained the upper hand. All that said, she has never deceived me.

The Cat-Fact: I cannot know how she would choose to die. The Human-Fact: I choose for her, then tell myself a story.I cannot tell my cat that I don’t want her days to be full of stress. Nor can I tell her how grateful I am for her quickness and humor, her curiosity, her regular gestures of what I receive as affection, her discretion. The Cat-Fact-ness of Zora is indisputable. So, too, is her artlessness, a lightness of being I have always envied, which has given me a singular pleasure. I can say nothing to her about all this. She understands human speech to a limited degree: before she went deaf, you hungry? was a question she never failed to respond to, and when spoken softly, the endearment you little monkey always made her purr. But much of the verbal language of human feeling has meant nothing to her. Touch is what counts.

As her life nears its end, words I’ve never used when talking to Zora come to mind now. Two words in particular: sovereign and splendid. Despite having lived in a place not of her choosing, Zora rules a kingdom all her own. And she gleams—shines—with authenticity. She’s incapable of compromise in that department. I aspire to her self-possession, never marbled by the fat of ego or menaced by the threat of humiliation.

In All My Cats, Hrabal alludes to several incidents that preceded his cat-killings, when in a fit of irritation he smacked or kicked one of his cats. This predisposition toward violence isn’t mine. Or so I say—yet do I truly know what I might be capable of? I’ve never hit Zora, though I’ve picked her up and dropped her like a brick onto the floor a few times, after she’d nipped me hard. Was that cruelty? Payback? Mere pique? What words capture those interactions? Where should I draw the line?

In his telling of it, Hrabal killed the kittens because he believed they wouldn’t survive if no one were present to feed them. I will end Zora’s life because I believe she wouldn’t survive if forced to move abroad. The Cat-Fact: I cannot know how she would choose to die. The Human-Fact: I choose for her, then tell myself a story. Between those two facts lie my own incalculable consequences.

__________________________________

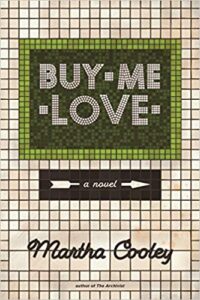

Buy Me Love is available via Red Hen Press.

Martha Cooley

Martha Cooley is the author of three novels—The Archivist (a national bestseller published in a dozen foreign markets), Thirty-Three Swoons, and Buy Me Love—and a memoir, Guesswork. Her short fiction, essays, and translations have appeared in numerous literary journals. She is a Professor Emerita in the English Department of Adelphi University.