The Ethics of Writing Hard Things in Family Memoir

Kelly McMasters Wonders What is Enough When Revealing Hard Truths

On a bright afternoon this past March, I walked to the front of a conference room in downtown Seattle and sighed with disappointment. Our AWP panel, “Motherlode: The Tripwire of Writing Real Family,” had been placed in room 329, large and lovely, except for the view through the giant wall of glass that would be the backdrop to anyone looking at our table of panelists. What they would see behind us: the gaping steel and shredded plastic mouth of a high-rise under construction.

It was unclear to me whether this building was being built up or torn down; what matters is the skeleton was visible, the heavy posts driving through the wall-less span stitching each individual floor together, the ugly orange and brown of metal left open to the elements. White plastic sheets billowed dramatically in the wind, like the slimy shower curtains in my old high school gym, never big enough to afford actual privacy.

There was the blue and white porta potties in the corner, the soon-to-be doors framed out in 2x4s, the thick wads of electric lines and plumbing, a body cleaved open to show its internal workings without the decency or protection of its rigid exoskeleton. As much as they’d tried to shield it, the guts of the building were visible, exposed for everyone in the conference room to see.

It occurred to me that this was what writing a family memoir feels like.

We’d come together that day to talk about just this: issues of exposure and protection, particularly of our children, in our pages. How do we, as mothers and writers, pull the plastic sheet so that it covers enough? And who, more importantly, determines when it is, in fact, enough? The children? The reader? The writer herself?

*

There are a handful of pages in my forthcoming book, The Leaving Season: A Memoir in Essays, that still keep me up at night. I went back and forth with one essay in particular that details an experience with Child Protective Services visiting my home. The event that triggered the visit occurred outside of our house, but CPS still came to our apartment because that is where the children lived. The investigator counted my smoke alarms, looked inside my refrigerator, my cupboards, as it that would magically tell her something integral about my family. Does my store brand-cereal make my children less safe?

There is no male comp category for “mother writers”; they are just writers.But the essay is not about CPS; the essay is about ethics, and art, and ambition, and the blurred lines between being an artist-parent versus a parent-artist, if there ever can truly be a difference.

For a period, I tried to edit out the CPS details from the essay, but the rest of the story didn’t hold together. For another period, I held the book in my hands without that essay included, but it felt like in many ways I’d written the entire book just so I could have the courage and distance to write that very essay, and not including it felt like a cop-out. One that only I would ever know about, but one I would not ever be able to unknow.

*

Back at the Motherlode panel, with the guts of the building stripped bare behind us for all to see, Sonora Jha talked about the power of playing with gaze, how different it felt to write from a man’s point of view in her novel, The Laughter, as opposed to her own in How to Raise a Feminist Son: A Memoir & Manifesto. She disclosed that after her memoir was published, she experienced fallout from people who chided her for exposing some of the men in her book, such as her ex-husband. This felt completely wrong-headed to her, she shared. “Instead of asking me to change, to keep quiet and protect these men, how about we ask the fucking world to change?” The room erupted into applause.

Her answer to that question was the book she wrote, which detailed her life as a mother to a boy who she quickly realized would one day become a man. She detailed these other models of men, and their effects, so that her son could know there was another way. By the time she wrote this book, her son was not a child any longer. She was able to share parts with him before publication and he was able to draw boundaries about what how and if he wanted to participate, on the page and off. But he did not ask her not to write her story. Because he understood that, even though he was on the page—in the title, even!—ultimately it was hers alone.

Even that doesn’t feel exactly correct. In nonfiction, the narrator is a version of you, but is not completely you—that would be impossible, even if one tried. The same is true when I write my children on the page. They are changing so quickly; one day, recently, my oldest son was simply taller than me. I understood this must have occurred gradually, centimeter by centimeter, but it still took me by complete surprise. I don’t know the date he stopped being shorter than me; I felt like one day I was looking down into his sweet face, and now, for the rest of my life, I will be looking up. My point of view has shifted. And so has his.

*

On a recent evening this past month, I sat in a church listening to Maggie Smith and Leslie Jamison have a gorgeous discussion about craft to celebrate Smith’s publication of You Could Make This Place Beautiful. The night truly was as perfect as the subsequent NY Times story made it seem, until the audience questions, when a man (perhaps the only man in the entire audience) asked about her decision to deploy her children on the page.

Smith quietly laughed before answering. “Deploying? That makes it sound like I’m sending them to war.” She talked about the inextricability of her parenting and writing. “I spend so much more time parenting than I do writing,” she said. She was always with her children; it would feel disingenuous to not include them. She was trying to cleave as closely to the truth as possible in this book. The children were integral to her experience of the divorce, and so including them helped her get closer to the truth of it all, which was her goal.

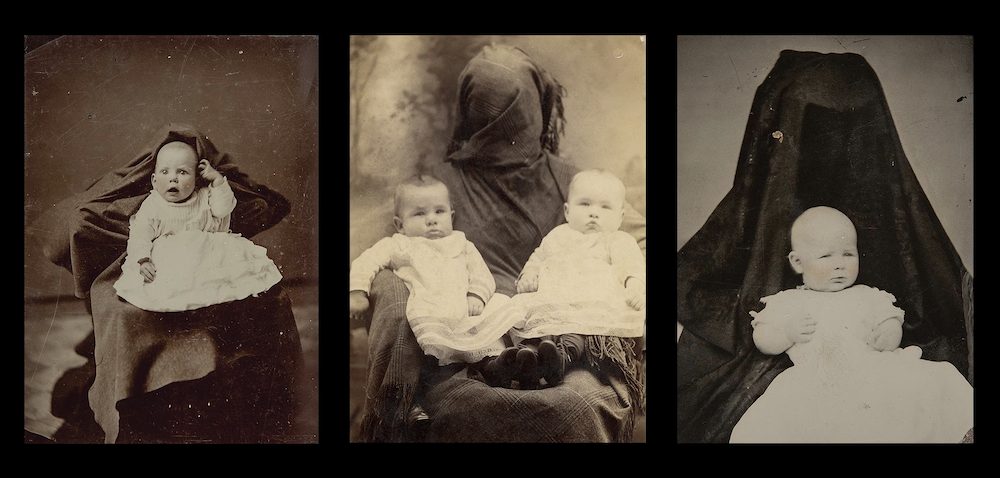

She talked about Hidden Mother Photography, the old practice of a mother sitting draped in black and holding still with an infant in their outstretched arms, in effort to erase the presence of the mother from the resulting photo. Instead, you end up with this ghost baby, disembodied and floating, and in most of the examples I could find, the mother’s outline was clearly there anyway, like some poorly executed Halloween costume.

Who, more importantly, determines when it is, in fact, enough? The children? The reader? The writer herself?This was how I felt when I tried to erase the hardest parts out of my essay, tried to erase the essay out of my book. Its absence left an awkward imprint. I could still see the hidden mother there. Everybody would still be able to see the outline of fear it left behind.

“I don’t want to drape either one of us under a black sheet,” Smith told the man.

*

At the panel that afternoon, Rebecca Woolf, author of All of This: A Memoir, posed this question to the audience. “Did you ever have a diary? And was that diary pink and did it come with a little lock and key?” There were murmurs of solidarity in the audience—yes, most of us had versions of this small book when we were kids. “I only recently came to understand that while I used to think that lock was there for my protection, to protect my secrets, I now understand that the lock was there to protect everyone else,” Woolf said. “These are designed to protect the world from the truths of women.”

Woolf’s memoir tightrope-walks through wanting a divorce, to the diagnosis and swift and difficult death of her husband, to the emotional, physical, and sexual reawakening that follows. I hate writing that word—reawakening—and yet, I can say from experience that this is exactly how it feels. Something was shelved, and then that something was revived. Have you ever watched a freeze-dried porcini re-plump in a shallow dish of water? The process can be unpleasant, unbeautiful, messy and awkward. It was this ungainly mixture—of motherhood and desire—that seemed to evoke distaste in some of her readers when the book came out.

At many of her events, Woolf shared, she would be asked what her children thought about her memoir, about her choices to write so explicitly about the difficult parts of her marriage and the explosion of desire and freedom that came after her husband’s death knowing that they might one day read it. She found this bananas. “They lived it with me,” she said. “It wasn’t a secret.”

She found it offensive, she said, that people presumed she was such a terrible mother that she had not carefully considered all these questions before choosing to write and publish this book, had not cut out pages and pages of material already. For the record, she shared, her teenage daughter chose her as the subject of a school paper this year, which was to write about her hero.

At our best, memoirists hope it is silence we are breaking, and not another person.Before our panel, we’d met for coffee to prepare, and this was the first topic that was raised: each of the writers on this panel had been asked publicly and relentlessly what their children/ex-husband/family thought about their books. Another of our Motherlode panelists, Joanna Rakoff, author of the memoir My Salinger Year, had just published an essay on Oprah Daily about leaving her first husband, and found this doubly true. “Do we ask these questions of men?,” she said pointedly. There is no male comp category for “mother writers”; they are just writers.

*

In the end, after multiple rounds of revision, I included the CPS essay in my book, with a note to the reader at the end that said: I attempted to write this essay many times without including our experience with Child Protective Services. At first, I thought my reluctance was the result of shame, but it soon became clear that I was not including this part of the story out of fear—fear of disclosure and judgment, of course, but also fear of opening myself and my family to the possibility of that terrifying knock on the door again. I decided to include this experience here for exactly that reason—so many of the incredibly brave and brilliant parents I spoke to in researching this essay have been cowed by a system designed to make us think it is our families that are broken when, in fact, it is the system itself that requires repair.

I wrote these words before the Motherlode panel, but I recognized the same sentiment in Rebecca’s locked pink diary, in Maggie’s pushing against the shroud, in Joanna’s core question, and in Sonora’s plea: let’s use our words as the shield instead of silence.

*

The view behind us that day did not disrupt the panel; indeed, in all the photos I have from that day, the construction is not even noticeable because of the angle of the photographers. The point of view excised the monster behind us.

I thought about this panel again last week while sitting in the back of a dim auditorium and listening to the poet Phillis Levin speak about her work as a poet. I’d been staring at the shocking pink of a blossoming dogwood tree just outside the one wide window in the room, thinking how out of place it looked against the staid academic browns and yellows inside, when she said, “Being a poet is violence in the same way spring is a violence; the violence of creation.”

The reminder that the creation—of a building, of a bud bursting forth, of a memoir—requires the breaking of something. It is safe inside—inside this auditorium, inside that conference room. At our best, memoirists hope it is silence we are breaking, and not another person. At our worst, we create anyway, knowing it will.

*

Our final panelist, Jane Wong, was not a mother herself, but wrote about her mother. She opened the hour by pulling out her mother’s dictionary and reading aloud some notes her mother had scrawled inside the cover as she was learning English. Jane built poetry from the words, and her love for her mother sang out into the audience.

When I later read Jane Wong’s memoir, Meet Me in Atlantic City, it occurred to me that my children might one day write their own memoir. Even though it feels to me like they don’t remember much of their childhood, I understand that the difference is that they don’t remember my version of their childhood. The parts I deemed the important scenes, that I observed from my perch as the central narrator. But I already know how quickly that POV can flip; one day you are looking down into the sweet face, and the next, and every day after, you are not.

My younger son was asked recently to write a travel narrative for school. The assignment required 10 pages and his teacher called me concerned after he handed in his first draft because he’d written to page nine and was still in the airport. But that’s the thing: it turns out, to him, the airport was the destination. What would have been one paragraph in my essay—because I’ve been in dozens of airports and have stopped seeing them at this point—was the entire story to him because it had been his first. He wrote details about packing, about the smell of the cab we took to the airport, about the magic of his blow-up neck pillow, even about the polka dots on the luggage straps I’d struggled to tie around his little suitcase; I’d forgotten about all these things until I read his pages.

And I found myself in his story, an undescribed character herding everybody along. My name was just Mom. I was not the center of the story, but I was there, because I am always there. And I recognized myself, even unnamed.

I don’t know if, when my children are older, they will recognize themselves in my pages, if they ever choose to read them. But I hope they know that although this is my story, this is not the only story. And that I look forward to them going out into the world and making their own.

____________________________

Kelly McMasters’s memoir, The Leaving Season, is available now.