The Enslaved Man Who Escaped George Washington—Twice

How 30,000 Enslaved People Gained Freedom by

Defecting to the British

Of our first five presidents, four owned slaves. The biggest slave owner among them was the father of our country, George Washington, who, together with his wife, Martha, owned about two hundred slaves at the beginning of the Revolution. Two of them became quite famous, for very different reasons.

William “Billy” Lee, Washington’s personal servant, was the only slave whom Washington freed outright upon his death. In John Trumbull’s famous 1780 painting of the president, Lee is depicted looking adoringly at his master and standing faithfully by his side.

At the other extreme of attitudes toward the master of Mount Vernon was a fascinating rebel named Harry, whose dogged determination to be free suggests that not all of Washington’s slaves found him to be the benevolent master whom historians have depicted. Harry’s first escape from Mount Vernon occurred on July 29, 1771. Washington was not amused: He “paid one pound and 16 shillings to advertise for the recovery of his property,” the historian Cassandra Pybus tells us. Harry was returned a few weeks later. Undaunted and determined to be free, Harry awaited a second chance.

That would come in the early years of the Revolution, on November 14, 1775, when John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of the colony of Virginia, issued an astonishing proclamation that freed any slaves who were willing to bear arms for the British Crown. They ran away in droves.

Pybus estimates that between 20- and 30,000 defected to the British side during the war—a stunningly high figure, since historians estimate that about 5,000 black men served in the Continental Army. Washington privately admitted that slave defections would gain momentum “like a snow ball in rolling.”

The general was right: Harry seized his opportunity and ran away in 1776, as did three white indentured servants. And they were not the last to do so. As late as April 1781, eighteen slaves fled the plantation. Though the war was raging, Washington was determined to retrieve his property and hired a slave catcher, who managed to return seven but not Harry.

Harry served nobly in Dunmore’s all-black loyalist regiment called the Black Pioneers. Rising to the rank of corporal, he participated in the invasion of South Carolina and the siege of Charleston, in charge of “a company of Black Pioneers attached to the Royal Artillery Department in Charleston in 1781.”

At war’s end, with the British defeat, Harry was part of a black community consisting of some 4,000 people who found safe haven in the British zone in New York, nervously awaiting their fate, since the victorious Americans insisted in the peace treaty that all runaway slaves be returned. Washington, despite the victory over British tyranny, remained ever determined to regain his escaped property. He instructed his army contractor, Daniel Parker, to do his best to find his slaves.

But the British kept their word. In July 1783, on board a ship named L’Abondance, a 43-year-old Harry set sail with his wife, Jenny, and 405 other black men, women, and children for Nova Scotia and freedom, in a settlement they named Birchtown.

__________________________________

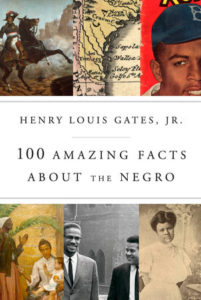

From 100 Amazing Facts about the Negro. Used with permission of Pantheon. Copyright © 2017 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and the Director of the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard University. The author of numerous books, including the widely acclaimed memoir Colored People, Professor Gates has also edited several anthologies and is coeditor with Kwame Anthony Appiah of Encarta Africana, an encyclopedia of the African Diaspora. An influential cultural critic, he is a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and other publications and is the recipient of many honors, including a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship and the National Humanities Medal.