Iva’s family wanted to see a Neanderthal, but the weather had them stuck in the cabin. Her brother-in-law suggested a hike in the rain, but Iva refused on account of her five-month-old. “She’ll be fine!” said Vinod. “She’s one of us—she’s a Pagidipati!” The last time Iva went along with that logic, she found herself hunched in a raft of Pagidipatis, the only one singing herself hoarse to a screaming infant in a life jacket.

The cabin sat in the foothills of the Shenandoah Mountains outside Luray, Virginia. Until a few years ago, Vinod had had trouble renting it out year-round, but that was before a pair of Neanderthals were discovered along the banks of the Shenandoah River. They were sisters, billed on Nightline as “the product of a bizarre and illegal in-vitro experiment.” Nature magazine took a more compassionate stance, referring to them as “endlings,” the last of their kind.

Tourists descended overnight. The bids on Vinod’s cabin spiked. The guest book was filled with testimonials from all over the world—Thank you we will never forget this noble species. / Incroyable!—that made no mention of the fire pit or the Carrara marble jacuzzi. People came for a glimpse into the Pleistocene past. They left with T-shirts that read: SURVIVAL OF THE SEXIEST.

“Well,” Iva said, trying not to sound hopeful, “why don’t you all go without me?”

“Z wants to hike, don’t you Z?” Vinod reached for the baby, who whipped around as if interested in the wallpaper.

“Sorry,” said Iva, secretly pleased with Z’s powers of discernment.

“Yeah, yeah,” said Vinod. “Stranger danger.”

While Vinod went to find his rain gear, Iva planted Z on the play mat, under the mobile that would provide about three minutes of entertainment, just enough time for Iva to wolf down a croissant.

Her husband called. Jai had caught the flu the day before they were to leave for Luray; he’d urged Iva to take Z and go without him. At least Iva and Z could enjoy some leisure time and avoid infection, and when was the next time they would get an all-expenses-paid vacation? Vinod ran a thriving urology practice in Chevy Chase, Maryland, but he was mercurial in his charity—stingy one minute and magnanimous the next. Jai was a middle school principal in downtown DC. Pride kept him from asking his brother for anything.

“Heyyyy,” said Jai, his head filling the screen, his nostrils plugged with twists of tissue. Looking at him made Iva feel fluish. “How’re my girls?”

She caught him up on the morning’s debate, how Vinod’s family was going hiking while Iva and Z would stay put.

“You won’t be lonely?” he asked, using a congested version of his parent-teacher conference voice. “What’ll you do there all alone?”

“I won’t be alone. I have Z.”

“And what’s it called? Moms Love Chocolate?”

“It’s not Moms Love Chocolate. It’s . . .” Iva lowered her voice. “Chocolate Mommy Luv.”

Chocolate Mommy Luv was a WhatsApp group of mothers of color from across the nation, a sisterhood of night owls, an altar upon which to rest their extremes of emotion unless the moderator deemed the offering harmful or off-topic. Chocolate Mommy Luv was unfortunately named.

A month ago, she’d turned to Chocolate Mommy Luv for advice on why Z was waking up every two hours at night. Mama-LlamaDingDong had blamed bed-sharing, saying Iva should never have pulled Z out of the crib, that this practice, in Mama-LlamaDingDong’s experience, had led her baby to graze on her milk all night long. PurpleRain said this was ridiculous, that she’d bed-shared with all four of her babies, concretizing their bonds and reifying their independent spirits. Sometimes, Chocolate Mommy Luv was a confusing place, which was comforting in a way, to know that no one really knew anything for sure, no matter how fiercely they expressed themselves.

“I haven’t posted anything lately,” Iva told Jai. “We’ve been keeping busy.”

“Huntin’ for Neanderthals?” said Jai, in a bad Virginia drawl. “Just kidding. You already told me what you’d do if you found them.”

“What did I say?”

“You don’t remember?” He looked concerned by her poor memory, recent conversations simply frittering away as a result of her perpetual sleep deprivation. “You said you’d break them out somehow.”

“Huh.” She brushed the pastry flakes from her fingers. “What would you do?”

“I don’t know. It’s pretty fucked up what’s happening to them, but I wouldn’t go rogue. That’s not really my style.”

A stampede of feet overhead. Vinod was hollering at his kids to find their rain pants, ponchos, moisture-wicking socks. “I should go help,” Iva said by way of goodbye, though her only intention was to help herself to another croissant.

*

Iva waved from the porch, waiting until Vinod’s SUV had turned the corner at the end of the lane. Then she shifted the baby to her left arm and passed through the galley kitchen, grabbing the leftover plate of pancakes, and followed the paving stones to the coach house.

Iva had volunteered to occupy the coach house so as not to wake the whole family with Z’s nocturnal shrieking sessions. The coach house was about the size of her apartment in DC, with a ceiling that soared over the living room and not one but two chandeliers—a massive wrought iron crown over the dining table and a smaller tiara over the king-size bed.

Z was whimpering by the time they entered the bedroom. As soon as Iva released her to the floor, she sprint-crawled to the walk-in closet. Iva did the secret knock—tap-tap with her fingernail, thud-thud with her knuckle—and cracked open the door. The Neanderthal sisters were huddled by the shoe shelf, glowering up at her. (Were they glowering, Iva wondered, or was the glower produced by their prominent browbones?) At the sight of Z, the younger sister broke into a grin and patted her knees as Z climbed into the nest of her lap.

The older sister was squatting with her back to the full-length mirror, wrapping one of Iva’s elastics around the end of her braid. (Iva’s brush was on the ground, clouded with coppery red hair, evidence that she would have to dispose of.) Both sisters were covered in fur capes and pelts, the costumes they’d been wearing when they escaped their compound. The furs were in fact blankets from West Elm, made to look authentically brutish and matted by their employer, Rustic Adventures LLC.

“They’re gone,” Iva said.

Tossing her braid over her shoulder, the older sister rose to her feet. The younger followed, carrying Z. Iva stepped aside for the three of them to venture into the living area.

“I brought pancakes,” Iva said, pointing to the dining table. Neither sister responded verbally; Iva had read that the sisters could not speak, that their voice boxes were buried down low in the chest, too low to make more than grunting utterances. Their lack of speech, she found, caused her to emote with excessive cheer. “No syrup this time!”

The older sister shuddered at the memory of syrup from their first breakfast together, almost two weeks before. She joined the younger on the rug, rolling the pancake into a tube before biting off the end. Z reached, but the older held it away and wagged a finger.

Watching the sisters eat seemed sort of rude, so Iva tidied her bed. Here and there she snuck a glance, wondering whether their paleontologist mother used to make them pancakes.

The sisters, Iva had read, were taken as adolescents from their mother who had taught them to read and write basic English. After the mother was institutionalized, the court assigned the sisters to a series of guardians. According to the older sister, the most recent guardian had tricked them into signing a ten-year contract with Rustic Adventures. At first, the sisters did as they were told, wearing fake furs, cleaning hides and turning spits of turkey meat while tourists watched from golf carts. The sisters grew to hate both roasted turkey and Rustic Adventures, and the night tours that left them vulnerable to ogling even as they slept under trees.

And so, in early June, the sisters fled their compound, traveling by night from one dark and uninhabited cabin to another until one day, they glimpsed a pair of headlights creeping up the driveway. They raced to the coach house, hoping to hide in a closet until they could flee in the night. The bedroom closet was crammed with suitcases and sleeping bags, but Iva glimpsed them as soon as she opened the door. They were crouched behind a space heater, their eyes the pale hard blue of rock crystal.

Her initial reaction—“Ohmygod shit shit!”—caused Z to cry hysterically. Before Iva could make a move, the younger sister stepped out of the hanging coats, waving her arms, hopping from foot to foot. Z went slack-jawed. The younger sister pulled a face, making Z laugh.

Slowly the older emerged and raised her palms in a pleading way. She mimed writing on her own palm and pointed to the kitchenette. Iva stepped aside, allowing the older to take the magnetized Post-it pad and pencil from the fridge and write in cramped capital letters: I CAN EXPLAIN.

Iva was mesmerized by their story—told in fragments and hand gestures—about the cruel guardian and the vultures of Rustic Adventures. When she asked where the sisters ultimately wanted to go, the older wrote: MOTHER.

“Yes, but where?” Iva asked, thinking that the older had misunderstood. The older underlined MOTHER. And it was true, Iva realized, a mother was a place as much as a person—in their case, a whole world.

They asked Iva not to tell anyone of their existence—not even the family members in the main house. Iva said nothing at first, still coming to grips with whatever the fuck was taking place in her kitchenette. She was ashamed, too, of screaming at the sight of the sisters, who were really just two orphaned girls of, what— seventeen? eighteen? The same girls she’d claimed she would find a way to save. Guilty, uncertain, she allowed them to stay that night, telling herself that by morning, she’d know what to do. As the days went by and Iva was forced to spend more time with Vinod, she grew convinced that no good would come of telling him about the sisters. He would insist, arms annoyingly akimbo, on notifying the authorities. Iva herself was skeptical of authority. Such skepticism was practically a job requirement at the immigration rights coalition where she used to work, in Maryland. The work had been constant and draining, calling lawyers to take on migrant children, visiting deportation centers, lobbying for stalled legislation. And though she had quit to take care of the baby—daycare being too costly—helping the sisters fired up the old engine of indignation, the sense of purpose that had once given shape to her days.

The sisters showed their gratitude by leaving her little bundles of wildflowers or wineberries on the kitchenette counter and keeping themselves confined to the walk-in closet. At night, Z’s screaming tested all reasonable limits of gratitude. It was the younger who emerged from the closet one night and offered to rock the baby in her arms. Exhausted, zombified, Iva watched as her daughter turned calm in the younger’s arms. Something about the younger’s smell or sway or strangeness had Z entranced, Stranger danger be damned.

*

After the sisters had polished off the pancakes, Iva poured them coffee.

The older held up the notepad: HOW MANY MORE DAYS?

“Till we leave?” Iva asked. “Three, I guess.”

The younger rested her cheek against the top of Z’s head. She seemed saddened by the prospect of parting. The older wrote: WILL U HELP US?

“Do what?”

GET OUT

“Sure. Wait, what do you mean?”

BUY COATS HATS HAIR DYE

“Hair dye? Really?”

DRIVE US TO CULPEPER TRAIN STATION—5:35 TO HOUSTON

“Wow. How’d you figure out the train schedule?”

The older pointed the pencil at the nightstand, where Iva’s phone lay atop a stack of magazines.

“How’d you unlock my phone?”

FACE ID WHEN U WERE SLEEPING

Iva imagined the older holding the screen to her snoozing face, waiting for the device to read her features. “That’s kind of invasive.”

U HAVE MANY OPEN TABS

Iva’s face warmed. Clearly the older had gotten a glimpse of Iva’s Neanderthal obsession, searches to do with clothing, honeygathering, and one about intersexual relationships between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens, a theory that explained, in part, the erasure of Neanderthals as a species. A valid question, Iva believed, possibly invalidated by her search query: neanderthals sex homo sapiens?

“Sorry.” Iva winced. “I was trying to learn more about you.”

WHY

“I’m just curious, I guess.”

The younger swatted at the older’s knee and signed something.

The older nodded emphatically.

SAY NOTHING ABT US TO ANYONE PLEASE

“No, of course not.”

4 EVER?

“I won’t. I promise.”

The older wrote down the address of a twenty-four-hour Walmart where Iva could obtain the clothing and hair dye. Tonight, after everyone went to bed. The younger offered to watch Z, but Iva said the baby loved being in motion and would be fine in the car seat. In truth, Iva had no idea how Z would react to being strapped into a car seat at three in the morning, but she preferred gambling on a tantrum than handing her baby over to sitters who were not only untested but another species altogether. She couldn’t exactly check references.

*

A few hours later, Iva was breastfeeding Z when she heard the slamming of car doors. Her breath caught. She’d expected to hear the SUV rumbling up the drive, forgetting it was a hybrid that only purred at low speeds. She darted a look at the sisters. They were already shutting the closet door behind them.

In seconds, Vinod’s twin boys were charging into the coach house—Iva scolded herself for leaving the front door unlocked— while she tried to snap up her nursing top.

“We saw the sisters!” they yelled as they ran to her chair, hopping in place with six-year-old fervor.

“When? Where?”

“On the hike,” said Kush.

“The hike, right.” Iva nodded, relieved. “Cool!”

Z twisted around to look at her cousins, delighted by the interruption. She reached for Luvh, who seemed momentarily hypnotized by Iva’s cleavage.

“So!” Iva said, trying to draw his attention upward. “What were they doing when you saw them?”

After a long vacant pause, Luvh said: “They were naked.”

“Yeah,” said Kush. “Up top.”

“The Neanderthal sisters were naked up top?” Iva said.

“And they had big ones, like yours,” Kush said.

“Okay,” Iva said briskly, “I have an idea: why don’t you guys wash up before dinner?”

“Nah” and “we’re fine,” they said in overlapping voices.

“Well, I have to finish feeding the baby, so.”

Kush asked if they could watch. Iva looked sternly at both boys, who looked sternly back, and said no.

*

In the evening, the adults convened on the deck. The rain had cleared, leaving behind a damp leafy smell that joined with the charcoal smoke of the grill. Vinod was flipping steaks, which he had jovially told Iva were not for her, as if she’d forgotten she was a lifelong vegetarian. Iva was just happy to take up a corner of the hot tub and spread her arms along the marbled sides. Her breasts were drained, her veins running with malbec. Her T-shirt puffing like a windblown sail.

Sitting on the edge of the tub was Myung, Vinod’s wife. She was holding Z, drifting her chubby little feet through the water, which they’d cranked down to a reasonable temperature. At one time, Myung had carried the twins, but years of intermittent fasting had whittled her hips to arrowheads. Her cheekbones glowed with a balm she once shared with Iva called Au Naturel, and that was how Iva thought of her, a natural at everything.

“Z’s loving the water,” said Myung, arching her eyebrows at the baby. “She’s remembering the womb.”

Iva nodded, feeling similarly enwombed. “How was the hike?”

Myung rolled her eyes. “The twins insist they saw the sisters.”

“I wish,” said Vinod. “The last three reviews on TripAdvisor were two out of five stars because apparently it’s my fault they didn’t see a Neanderthal.”

“I just hope they’re safe,” said Myung, beautiful natural Myung. Iva loved her. Iva loved everyone gathered here, maybe even Vinod, until he said, “Once we get them back, we need to build a wall. Not a brick wall. Something with gaps they can see through.”

“You can’t do that,” Iva said. “It’s inhumane.”

“Hello, it’s for their own protection? An eight-lane interstate wraps around the park. I bet they’ve never even seen a car before—”

“What about more security cameras?” Myung suggested.

“We have cameras,” Vinod said. “They keep smashing them. Do you guys have any idea how freakishly strong they are?”

Iva hadn’t considered their physical strength. She’d always assumed them to be fragile, childlike, in part because she was at least six inches taller than both of them.

“I got some new surveillance cameras,” Vinod said. “Spy quality. I’m gonna install them where no one can see.”

“And where’s that?” Iva asked.

“Where no one can see.” He winked at her.

“Well, don’t rig them up during our vacation,” Iva said. “I don’t want to be surveilled.”

“Nothing to worry about if you’ve got nothing to hide,” Vinod said.

“He’s joking,” Myung said. “He couldn’t install a nightlight without help.”

Hotly, Vinod listed the many things he had assembled and installed around their house. Iva took the opportunity to side-climb out of the tub.

“I’m tired,” she said. “Think I’ll go back to bed.”

“You okay?” Myung asked.

“I’m fine. Just dehydrated, probably.”

“Have a steak then!” said Vinod. “Just kidding, I have some corn on the cob and baked potato for you.”

Iva said she’d have it all: the corn, the potato, and two steaks.

“For who?” Vin asked.

“Me.”

Iva could feel the spotlight of their surprise. The two times Iva had eaten meat in the past were by accident; once informed, she immediately went to the toilet and threw up. And now here she was with a paper plate practically bleeding into her palm.

“Yeah,” Iva said, trying to sound tired. “I’ve been feeling weak from all the breast-feeding.”

“You could have low blood pressure,” Vinod said. “Steak would definitely help with that. I bet it even helps with milk, you know, stimulation. Rare or medium rare?”

Iva gambled on rare.

“Attagirl,” said Vinod, draping two glistening slabs on her plate alongside a foil-wrapped potato and corn on the cob.

“Should Vin take your blood pressure?” Myung asked, watching her with concern.

“No one is taking my anything,” Iva said. “I’m just going to watch some TV and eat in bed. But I’ll come back for the baby.”

Iva strode away, her jaw tight. A fucking wall? Had everyone lost their minds? She stood on the porch of the coach house for a moment, breathing deeply against competing waves of anger and worry. She wondered if she should call one of her former colleagues, someone she trusted, to offer the sisters legal counsel. Iva wasn’t a lawyer. She was just a mom in the middle of nowhere, bearing a paper plate of steak. Then again she knew the sisters would refuse any offer of outside help. Homo sapiens, they believed, were not to be trusted.

YOU ARE DIFFERENT, the older had written. NOT LIKE YOUR KIND.

Conferring with her sister, the older added: MORE LIKE MOTHER.

Iva knew they’d meant this as a compliment, but being compared to a woman under psychiatric surveillance—well, it troubled her.

*

Only later that night could Iva relax again, after returning from Walmart with several boxes of hair dye in French Roast. Each sister held her head over the sink, a towel draped over her shoulders, as Iva worked the dye through their coppery roots. The younger applied the rest of the dye to Iva’s head, though Iva knew the brown wouldn’t show up in her black hair. She enjoyed the scalp massage, their strange little sorority of stained towels and oil-slicked heads.

While waiting for the dye to set, they tried on their new clothes: cheap jeans, bucket hats, fleece coats. WHY MOM JEANS? the older asked, after reading the tag. Because the waistline is so forgiving, Iva had said. Because of all they hide. Because they were half off. Fully dressed, the older sashayed across the rug, then paused to swipe a finger across her palm. They all shared a laugh. After rinsing and drying their hair, the three of them went to bed. No sooner had Iva fallen asleep than Z began to whimper. Only half-awake, Iva heard the younger pick up the baby, making a little grunting sound as she jostled and rocked her. Soon Z had drifted off again, and Iva mumbled something by way of thank you or how’d you do that, before descending back into a dream that was remarkably anxiety-free, in which Patrick Swayze was begging her to leave her life behind and run away with him into some sexy, sweaty beyond.

*

The next morning, while Vinod was out kayaking, Myung and Iva took the kids to Luray Caverns. Iva volunteered to drive so she had some excuse for holding onto the keys. At dawn, she would load the sisters and Z into the SUV and drive to the Culpeper train station. Just in case, she’d leave a Post-it on the fridge: took car, driving Z to get her to sleep.

The prior night’s slumber party had Iva buzzy and exhausted, but she managed to take note of the highway signs, including the exit that led toward Culpeper.

“You okay?” Myung asked warily when Iva’s mouth fell open again.

“Oh. Yeah.” Iva shivered. “I was up all night.”

“Z give you a hard time?”

“No, it was just me. Couldn’t sleep for some reason.”

“Do you think,” Myung ventured, “that you might be spending too much time on your phone? I know that Chocolate Mom group means a lot to you, but you can also call me or your mom if you want to chat.”

Calling her mother rarely ended well. Every conversation led back to the same Nike-inflected statement motto: “You all”— meaning the entirety of Iva’s generation—“think too much. We just did it.”

Fighting a yawn, Iva said, “Thank you. I appreciate that.”

A silence ensued, the kind that usually precedes some sort of emotional bloodletting. Iva decided to cut to the quick. “I used to talk to my colleagues,” she said. “I miss them. I miss my job.”

“But, Iva, being a mom is the most important job there is.” Iva glanced at Myung, who gave a brain-dead grin.

“See, that’s called acting,” Myung said. “Did I tell you I’m trying out for a play next week?”

They talked about the community theater in Chevy Chase, the upcoming adaptation of Steel Magnolias. Four Southern women, but multicultural this time. Myung would be trying out for the Darryl Hannah character, a born-again Christian.

“I didn’t know you could act,” said Iva.

“I used to, in college. That’s how Vinod and I met, doing Pygmalion.”

“Vinod was in Pygmalion?”

“He did the lights. So he says. To be honest, I don’t remember meeting him at all—isn’t that terrible?”

“It’s weird,” Iva said. “Vinod is pretty memorable.”

“I know,” Myung sighed. “To be honest I barely remember anything from college, from yesterday even.”

“Yeah, the other day, I forgot my cell phone number.” “That’s nothing. I’ve forgotten my kids’ names.”

They named other outlandish things they’d forgotten: the lead singer of Queen, half the lyrics to the national anthem, how to spell “banana.” They laughed at how dumb they’d become, how functional they made themselves seem.

Just as Iva was beginning to relax, Myung tilted her head and asked, “Did you color your hair?”

Iva tucked a lock behind her ear. She’d thought her black hair would subsume all signs of French Roast. “Maybe a week ago? Before we came to Luray?”

Myung nodded. “It’s subtle.”

Iva curled her fingers around the steering wheel to hide her dye-stained fingertips.

*

In the caverns Iva forgot her own exhaustion, as awestruck as the first spelunker to worm down a hole in a Virginia hill and find himself on another planet entirely. Pleats and drapes of glistening flowstone. Ceilings bristling with stalactites, practically glowing as they narrowed to meet the stalagmites. The tour guide called the ones that merged in the middle “a marriage.”

“See that?” Iva said to Z, who was strapped to her chest. “A marriage. It takes hundreds and thousands of years to form.” Subdued by the shadows, Z was already nodding off.

Iva fell in step with the tour guide, a well-tanned young man with a pleasant drawl. He stopped the group by a chasm where, he said, a Neanderthal woman’s remains had been discovered two decades ago, her skullcap so perfectly pickled in a pool of water that a paleogeneticist was able to extract its DNA, which was then inserted into a hollowed-out human egg cell, which in turn was implanted in the womb of the paleogeneticist. That single fertilized egg split in two, resulting in the birth of the Neanderthal twins, whom the paleogeneticist raised until they were discovered and turned over to the State, which allowed them to remain in their native habitat under park supervision, while their mother was in a mental health facility somewhere in California. “So although Dr. Collier displayed some questionable medical ethics, thanks to her, we have the sisters.”

Rustlings of unrest. A man behind Iva declared that he hadn’t seen the sisters, separately or together, during the entirety of his ten-day stay. “You guys should advertise when it’s low season,” he said. “That’s why we came down here in the first place.”

“I bought a special camera for this,” said a woman.

“Actually,” said the tour guide, “photography of the sisters is prohibited. In the past it’s led to some violent confrontations.” The woman insisted that it was a telephoto lens, the kind that nature photographers use to capture wildlife from far away.

The sisters had told Iva about certain VIP tour groups that had been allowed to get uncomfortably close, so close that the older once heard a donor talking about her ass. She gave him the middle finger, earning herself a sharp rebuke from Rustic Adventures. The sisters were not to respond to tourists, forbidden from letting onto the fact that they were equal parts Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens, the latter half inherited from their mother. This was not what modern man wanted to hear, said Rustic Adventures. Modern man wanted the authentic experience of stalking another species of human—familiar and yet essentially, impossibly, different.

But that was hardly a violent confrontation, Iva thought, annoyed at the tour guide for making the sisters sound so savage. Unless there was some other incident they hadn’t told her about.

*

At the cabin, in bed, Iva nursed until Z dozed off with the nipple still in her mouth. Transferring Z into the travel crib would only cause her to gasp awake—some primal fear of falling that kicked in no matter how gently Iva lowered her onto her back. Soon Iva had surrendered to her own fatigue, and the harmonic rhythm of their breathing, and fell asleep.

In the seconds before Iva opened her eyes, she could hear the steady breathing of someone standing close by.

“Weird . . .”

Iva opened her eyes: it was Luvh, kneeling by her bedside, head cocked to examine the juncture where Z’s mouth met Iva’s nipple.

“It’s not weird,” Iva said groggily, deciding to turn this awkward moment into an even more awkward teaching opportunity. She explained that the milk was coming out of her breast, and that Luvh had also drunk from his mother’s breast for a very, very long time. Luvh tried to process this information, but it was clear that milk flowing from a breast was about as logical to him as Kool-Aid pouring from a doorknob. Meanwhile Z’s gaze was awake but unfocused, on the verge of a postlude Iva called “singing into the mic.”

“Can we talk later?” Iva asked Luvh, snapping up her nursing top.

“But I have to tell you a secret,” he said. “You can’t tell anyone.”

Iva assured him his secret was safe. They went through the motions of double and triple-promising before he confessed: “We didn’t see the sisters on our hike. We lied.”

“That’s okay.” With a pat on the shoulder, Iva asked him to keep Z from rolling off the bed and went to look for a fresh nursing top. The cups on her current top were stiff as papier-mâché. “I mean lying isn’t great.” She sniffed a bra. “But your lie didn’t hurt anyone, so it’s fine.”

When Luvh didn’t reply, Iva turned. He was letting Z grasp his finger and wag it up and down, a worried look on his face.

“I did see her though,” he said quietly. “I came down to drink grape juice in the night and I saw her. She was in the kitchen, going through drawers. But then this morning I thought maybe it wasn’t her. Cause she was wearing jeans and Neanderthals don’t wear jeans. I told Mommy what I saw but then she got mad at me for making things up and also for drinking grape juice at night. She says that’s why I have cavities but I just get so thirsty . . .”

Iva released the breath she’d been holding throughout Luvh’s testimony. “It was probably just a dream, sweetheart.”

“It wasn’t!” he shouted tearfully, dropping Z’s hand. “I’m telling you, I saw her!” He ran away, slamming the coach house door behind him.

Iva turned the lock and watched through the blinds as he stormed across the lawn, his hands buried in his pockets. Once he was safely out of sight, she put Z in the travel crib and charged into the walk-in closet. The sisters were passing a stick of string cheese between them. “What were you doing in the main house?” Iva said.

The younger bowed her head. The older chewed in defiance, swallowing before taking up her notepad.

NEED $$$

“So you tried to steal it? I told you I’d give you money.”

HOW MUCH

“I don’t know . . . a hundred and fifty dollars. It’s the max I can withdraw from the ATM.”

The sisters looked disappointed.

“I already bought the hair dye, the clothes, all of that . . .” Iva watched the younger pick at the hem of her distressed mom jeans. She imagined them wandering around Houston with their bucket hats pulled low. Where would they live, what would they eat? “Okay, look, I’ll get you a hundred and fifty more when we get to the train depot. There’s probably an ATM around there. Just promise me you won’t take anything from the house. Agreed?”

The younger nodded. The older offered her sister the rest of the string cheese, but the younger shook her head, as if she’d lost her appetite. The older shrugged and shoved the rest into her mouth before lying down with her back to Iva.

*

After dinner and a movie with the family, Iva retired to the coach house with Z, carrying a bag of soup cans and ramen cups. All day she’d been hoarding non-perishable pantry foods for the sisters to take on their trip. Halfway down the paving stones,

Myung caught up to her.

“Need me to watch Z?” she asked. “Or I can help you pack.”

“I have to feed her,” Iva lied.

“You just fed her, I thought.”

“Not much,” said Iva. “I can tell she’s hungry.”

Z smiled at Myung in the least hungry-looking way possible. “Just let me keep you company for a while,” said Myung, and took the baby into her arms.

Leading the way to the coach house, Iva braced the bag against her body to keep the cans from clanking. “Here we are!” she sang out as they entered, hoping her falsetto would reach the sisters.

Myung wandered around the sitting area with Z on her hip. “I almost forgot how cute this place is. I think it used to be where the horses were kept—not by us,” she added quickly. “The original owners.”

If Iva was supposed to take offense, she’d missed the opportunity, too busy trying to shove the bag of cans into a cabinet. “Yeah, I’ve loved staying here.”

“Oh, you wanna show me your crib?” Myung said as Z lunged toward the bedroom threshold.

“What’s there to show?” Iva asked, but Myung and Z had already crossed over, and she could hear Myung naming the crib, the window, the bed, the closet.

“Yes, that’s the closet,” said Myung. “What’s up, baby? You wanna look inside?”

Iva closed her fists, sickened by the squeak of the door hinges, the flick of a light switch. She waited for Myung to scream.

Iva screamed first. “Myung! Myung!”

Myung rushed out of the bedroom with Z. “What—what is it?” “You should leave,” Iva said. Myung looked bewildered and annoyed. “I think I have a sore throat.”

“Why are you screaming if you have a sore throat?”

“I just remembered—don’t you have that audition coming up?” Myung’s face fell. “Oh shit. I mean shoot.” She returned the baby to Iva’s arms and took several steps back. “Do you think you have what Jai has?”

“Possibly. Probably.”

Iva watched Myung rewind over all the time they’d spent together, the entire car ride of shared infected air. “And you’re only telling me now?”

Iva began to apologize but Myung waved her off. “It’s okay, I should go. I’ll make us some golden milk and leave it on the stove.”

Iva thanked Myung and locked the door, then hurried to the walk-in closet, Z on her arm.

The door was open, the sisters nowhere to be found.

“Hello?” Iva called, her voice cracking. The sisters were gone. They’d left without telling her. Had she done something to upset them? Was it the money discussion?

Z gave a grown-up sigh and rubbed her ear, a tired sign. Time for a nap. Time to get back to life as Iva had known it, taking care of her child, just the two of them again.

One of the suitcases, lying on the floor, moved slightly. Iva’s heart leapt. She flipped back the lid, and there was the younger, barely able to sit up before Iva had embraced her.

*

It was midnight. The younger had gotten Z to sleep in the travel crib where she would probably stay for the next three hours, until Iva would have to feed her before the journey to Culpeper. For now the sisters were asleep in the closet. Iva should have been sleeping too. Instead she was in bed with her phone, catching up on Chocolate Mommy Luv threads, trying to make up for her silence by remarking on old comments. BlueLotus lamented the fact that she was still pureeing foods for her LO (Little One) who refused to chew his food, leading her to wonder if she should accept the gastroenterologist’s advice and subject her LO to a scope. Iva joined the twenty-one other mothers who gave this idea a thumbs-down. (Your LO will figure out how to chew eventually, wrote MamaLlamaDingDong. He won’t be drinking his food in college!) Iva treaded gently into the perennial bed-sharing debate. She offered her vocal support of paid leave for new parents and her neutral comfort to SailorMoon75, whose husband had maybe slept with the housekeeper.

Immediately Iva received some private messages: Glad you’re back! . . . We missed you! . . . Where ya been? Vague as they were, these messages lifted her up.

Sorry to be out of touch, Iva wrote back. We’re on a vacation . . . She changed “vacation” to in the mountains with in-laws.

Some of these women were deep in the sleepless trenches and in no state to hear about other people’s getaways.

Has it been fun? BlueLotus wrote back. Ready to say goodbye?

No, not ready, Iva thought. Not ready at all.

And here Iva paused, struggling to find the words, just as she struggled whenever she tried to describe her interactions on Chocolate Mommy Luv to Jai. He always nodded, slightly tuned out. This was the loneliness of having a life online. To everyone else, it was a mirage.

And now Iva had gone a level deeper into unreality. She couldn’t even explain to her Chocolate Mommy Luv friends how meaningful the last two weeks had been, how unexpected and exhilarating. How could it be coming so quickly to an end?

She closed the app and lay for a long time listening to the white noise machine. It swallowed sound the way her mind would swallow memory in the weeks to come, when the nights would unfold as they had before, unending, inevitable. Sometimes it seemed that the only memories she could claim were the ones captured by her phone.

And then she had an idea.

Switching the phone to silent, she stepped softly to the walk-in closet and opened the door, the hinges mercifully quiet.

Moonglow fell through the skylight, washing the sisters in blue. They lay on their sides, the older’s arm over the younger’s waist. Iva raised the phone, opened the camera app, and centered the sisters in the crosshairs. Three taps. She stepped back and closed the door.

As she returned to her bed, guilt gave way to a little burst of joy. She had them now. She would always have them.

Iva was still staring at the photo when she felt a tap on her shoulder and wheeled around.

There was the older sister, holding Z.

Iva stiffened. Shoving the phone in her back pocket, she gave a sheepish smile. “Sorry, was she fussing?”

The older didn’t move. Z was deep asleep against the crook of her neck, emitting a wheezy snore that Iva could almost feel caressing her own throat.

Iva reached for her baby. The older twisted away, angling herself so that Z was just beyond Iva’s grasp.

Slowly Iva’s arms fell to her sides. She understood the threat, could feel it in her womb, where sometimes a movement ghosted through her as if the baby had never left her body.

Now the older held out a hand, palm up. Her fingers made a summoning motion.

Shaking, Iva tried not to drop the phone as she placed it in the older’s hand. Once more Iva reached out her arms, she and Z falling into each other.

She watched the older swipe through photos. One picture, presumably of the sisters, made the older look up at Iva with a peculiar expression, as though Iva had turned into an object of curiosity, a stranger of uncanny likeness.

After deleting the photos, the older set the phone on the nightstand and went back to the closet, shutting the door behind her. Iva swayed from side to side. She dipped her nose into Z’s neck, the baby’s pulse flitting against her lips as she whispered words of comfort the baby didn’t need, so primal was her trust in the arms that kept her from falling. Iva herself wouldn’t sleep tonight. She would be counting the minutes until she could drive the sisters to the train station, where she would tell them to ride to the end of the line, then get off and keep going and never come back.

__________________________________

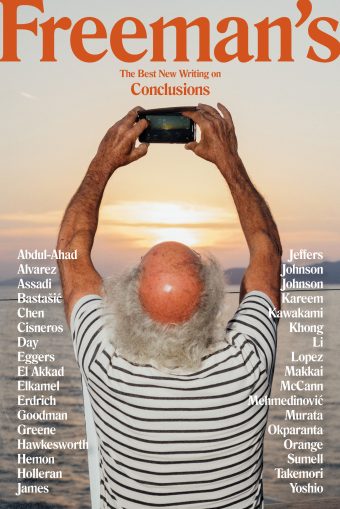

From FREEMAN’S: Conclusions. Used with permission of FREEMAN’S. Copyright © 2023 by Tania James.