The Emotional Aftershocks of Alice Adams' Most Celebrated Work

On Families and Survivors: "I know it will be hard for you to read."

“I really said it all in Families—Christ that was 30 years of my life,” Alice Adams told Max Steele after the book was published. The creative and editorial process that enabled Adams to put three decades into 211 pages that told a coherent story owed much to Victoria Wilson. The “extremely bright” young editor explained that Adams’s tendency toward tight structure and character precision hurt a novel: “I think you have to decide who the important characters are, how they fit in with one another . . . and how they build the novel.” Wilson told Adams to leave the manuscript of Families and Survivors home on her fall 1973 trip to Europe. Rather, she urged her, “let it enter your dreams . . . you can be sure your mind is typing away even if your fingers aren’t.”

Just finishing her first year as a book editor, Wilson found herself working with a mature author who was, nonetheless, willing to be heavily edited even as she sometimes opposed Wilson’s suggestions. Both women typed out their thoughts in lengthy letters, a polite, laborious process that led to exceptional clarity. Thus Families and Survivors became the honeymoon book for a sometimes difficult but ultimately enduring editorial marriage.

After returning from Europe in October, Alice rewrote many chapters, eliminated and combined characters, and got it all back to Wilson in December. The result, Wilson found, was “at the stage where instead of reading it with the purpose of trying to suggest changes, I just found myself soaking it in . . . it is simply fun to read.” After that, author and editor spoke on the phone for the first time, beginning a personal friendship that complicated and strengthened their work together. In the end, Adams credited Wilson with an “extraordinarily perceptive understanding of what I’m trying to do.” The cover Wilson planned confirmed that. Greenwich Village artist Joan Hall’s assemblage of timepieces and wedding rings surrounds an image of a couple: “How very odd,” Alice said, “that that girl looks like me at 14 or 18 or something.” Families and Survivors was scheduled for publication the following fall.

While Families and Survivors was in production, Adams turned out a stream of new short stories and began a new novel. Liberated by Nic’s death, she composed her best, most innovative investigations of her childhood and her parents’ marriage. In a trilogy called The Todds—“Verlie I Say Unto You,” “Are You in Love?,” and “Alternatives”—she boldly explored her memories of Verlie Jones and her parents and Dotsie. But lest anyone take these stories as pure biography, she called herself Avery Todd, gave Avery a living brother named Devlin, and invented characters like the poet Linton in “Are You in Love?” (based on Billy Abrahams) as she needed them. The Atlantic Monthly bought both “Verlie” and “Alternatives.” Alice worried about how these stories would be received in Chapel Hill, even though her stories call the town Hilton—after the place near which the troubled house named Howards End stands in E. M. Forster’s novel.

In the character of Barbara, Alice characterized her stepmother as a woman who spared herself the trouble of considering “alternatives” in her life. Both Lucie Jessner and Max Steele assured Alice that Dotsie could not possibly object to “Alternatives”—“a good deal of tenderness in that story,” Jessner said—but in the end Dotsie felt “hurt” by it and told Jessner so. Thanks perhaps to Southern politeness and its attendant deceptions, Alice received such information secondhand and never had conversations with Dotsie about it. It was probably the character of Tom Todd in “Alternatives” that most upset Alice’s stepmother: Nic, as Alice admitted to Max, came out as a “ghastly old prick.” In Chapel Hill, one person told Max the story showed how “bitterly” Alice regarded her father, while another thought it showed that she regarded him with “so much love.” Max insisted, “It would be hard to say what your feelings are since artists are, behind the great revelations, reticent people.”

Alice intended “Roses, Rhododendron” as “a sort of Valentine,” she told Judith in advance of its appearance in the New Yorker, but said, “I know it will be hard for you to read.”

For Adams these stories were part of “a curious rethinking” of her mother that began after Nic died. A “very moving” letter from Judith Clark Adams after Nic’s death inspired Alice to write her most celebrated story. The letter (lost, unfortunately) made Alice think about what the Adamses had meant to Judith: “It occurred to me to try to write a story about us from her point of view. And, with radical changes of course, that is how this story came about.” Looking at her family as an outsider proved “interesting and instructive.” In “Roses, Rhododendron,” Jane Kilgore moves from Boston to a North Carolina town with her “big brassy bleached blonde” mother. Once there, Jane becomes the medium for telling the story of a family, their house, and their countryside:

The house I fell in love with was about a mile out of town, on top of a hill. A small stone bank that was all overgrown with tangled roses led up to its yard, and pink and white roses climbed up a trellis to the roof of the front porch . . . the lawn sloped down to some flowering shrubs. There was a yellow rosebush, rhododendron, a plum tree, and beyond were woods—pines, and oak and cedar trees. The effect was rich and careless, generous and somewhat mysterious. I was deeply stirred.

Adams tells the story in this swirly, associative manner throughout. There’s seemingly no pattern to the revelations about house, family, and countryside that Jane loves, yet Adams’s now well-established ABDCE format is there, its climax coming when Jane sees “the genteel and opaque surface of that family shattered” by voices raised and words going out of control, exposing a “depth of terrible emotions” that Jane does not comprehend until later.

Imagining her story from another’s—Judith’s—perspective allows Adams to witness herself as Harriet. Here is her own childhood, seen primarily through love rather than fear. As the youthful friendship once did, “Roses, Rhododendron” enacts a peaceful separation from home:

I thought Harriet was an extraordinary person—more intelligent, more poised and prettier than any girl of my age I had ever known. I felt that she could become anything at all—a writer, an actress, a foreign correspondent (I went to a lot of movies). And I was not entirely wrong; she eventually became a sometimes-published poet.

In this roundabout way, Adams could praise herself as never before—though she had already outpaced “sometimes-published” Harriet Farr.

The New Yorker turned down “Roses, Rhododendron” in 1973 but accepted a revision at the end of the next year. A young fiction editor, Frances Kiernan, did the editing. It appeared in the magazine early in 1975 and was included in Prize Stories 1976: The O. Henry Awards (with third prize) and in Best American Short Stories 1976. It brought fifty fan letters (“a practically perfect story,” according to old acquaintance and professor Bill Webb in Cambridge). Alice answered every one.

“I really don’t want these idols made human although my caring for you does make me want to see it from your eyes.”

Other reactions were more complicated. Alice intended “Roses, Rhododendron” as “a sort of Valentine,” she told Judith in advance of its appearance in the New Yorker, but said, “I know it will be hard for you to read.” Indeed, Judith was not “crazy wild” about the story.

Alice’s parents had been idols to her, and she said to Alice, “I really don’t want these idols made human although my caring for you does make me want to see it from your eyes.” Judith was also troubled by the raunchiness of “her” mother, the story’s Margot. Alice replied immediately: “I invented raunchy Margot . . . in no way like [Judith’s mother] Dorothy.” For the story, she explained the mothers needed to be so different that they would avoid meeting. “But it’s terrible—one makes these distortions, and then one’s favorite friend thinks: God, did she see Dorothy as raunchy? I do see the enormous difficulties in reading something by an old close friend. Bob has something of the same trouble,” Alice concluded. Judith understood and her friendship with Alice thrived.

Another letter came from Willie T. Weathers, a retired Latin professor at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College who described herself as one of Agatha Adams’s best friends. She congratulated Alice on her literary success and on fulfilling Agatha’s “frustrated ambition” but scolded her for portraying her mother as a “sad and passive figure” in her stories. Agatha, she argued, “combined brains, personal magnetism, a delightful sense of humor, and talents in many fields.” She hoped that sometime Alice would “try to paint her in the round.”

That, of course, was the project Adams was undertaking in her continual revisiting of her house and family in Chapel Hill. Weathers seems not to have registered the entirely new—invented, certainly not passive—narrative with which “Roses, Rhododendron” endows Harriet’s mother. Emily Farr, we learn through epistolary gossip, left her husband “without so much as a by-your-leave” and went to work at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington. The narrator imagines the Farrs “happier apart” and approves Emily’s valiant decision. Alas, when Lawrence Farr falls ill, Emily returns as his final caretaker and herself dies shortly after him. So much for the liberation of Agatha.

Adams does make “Roses, Rhododendron” a Valentine to Judith by ending the story with a letter to the narrator from Harriet (herself). During her father’s agonizingly long death, Harriet writes, she kept in her mind a picture of the two of them on their bikes at the top of the hill: “Going somewhere. And at first I thought that picture simply symbolized something irretrievable, the lost and irrecoverable past, as Lawrence and Emily would be lost.” But through story and through Judith, Adams has recovered that past. With both her parents dead and the house in her stepmother’s possession, the storyteller has revivified her friendship with Judith. With a neat gambit, Adams wraps it up by having Jane’s husband read Harriet’s letter and say, “She sounds so much like you.”

__________________________________

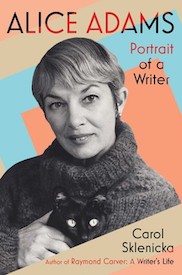

Excerpted from Alice Adams by Carol Sklenicka. Copyright © 2019 by Carol Sklenicka. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Carol Sklenicka

Carol Sklenicka is the author of Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life, which was named of one of the 10 Best Books of 2009 by The New York Times Book Review, and Alice Adams: Portrait of a Writer. She lives with poet and novelist R.M. Ryan in northern California.