I thought I had arrived at the Throne of Grace the first time I saw Spelman.

When Mama and I visited the campus not long after our arrival in Atlanta in the fall of 1932, we stood staring—staring, without saying a word—at the stately white-columned buildings, the magnificent Sisters Chapel, the lush green lawns ringed by dogwood and magnolias, all so flawless they looked like they’d been painted. That such a place lay within my grasp—I, who’d begun my education in a rotting frame building with rickety outdoor stairways and privies and a play yard of bare clay—seemed barely comprehensible. Right then and there, I decided Spelman was God’s answer to the prayers of the world.

Yet 20 feet from the place where the trolley stopped, that vast expanse of sheer perfection changed into a filthy, poverty-stricken, hate-filled city. Atlanta had always been a racial hell, just as Grandma had told us, but the grinding poverty of the Great Depression made it worse. Whole families—black as well as white—lived on the streets and in the alleyways; men walked aimlessly about looking for jobs that didn’t exist; women foraged for food in garbage cans. What few pockets of goodwill might have existed between blacks and whites before the Depression, the fear of starvation and homelessness killed.

Each time Mama and I boarded the trolley, we took seats all the way in the back and held our breath at every transfer point on the 15-mile route from the city to the Hurleys’ home in the town of Decatur. I watched the black and white passengers crowd onto the cars, jostling and elbowing their way down the aisles, my whole body stiff with dread until we reached the Hurleys’ home, a safe haven in the midst of that awful city.

At least, that was the way Mama and I perceived it in the two years it took for the two of us to save the $75 for my freshman tuition and see to my admission to Spelman. Had my mother sensed anything amiss in the home where I was to live, she would never have departed for Charlotte in the spring of 1934. It was in fact only after Mama left that Mrs. Hurley began to change toward me, to grow ever so slightly cooler and more distant.

At first, I told myself I was misreading her. She had, after all, taken Mama and me under her wing, done us a hundred kindnesses over the years. I knew, too, that she held me dear for the care I showered on her little boy, Bailey Hurley, Jr. But on the afternoon when my official letter of admission arrived from Spelman and I held it out for her to see, excited and proud, I sensed that all was not well.

“Well, my goodness gracious,” she said, raising her eyebrows and looking straight at me and not at the letter, “why on earth do you want to go to Spelman?”

There was a coldness in her genteel voice I’d never heard before. I stared at her, wondering if I’d understood her question correctly.

“Mama wants me to go,” I finally answered. I had never imagined that anyone as lovely as Mrs. Hurley could sneer, but she did. Her pretty mouth twisted, and without another word she turned and left the room.

Though she made no move to stop me from beginning classes, I walked on tenterhooks in her presence from that day forward. I felt her eyes upon me as I did my chores, watching me, as though trying to puzzle out something she truly could not comprehend.

“Just look at Mrs. So-and-So’s girl,” she’d say out of nowhere, naming some young woman who worked in service for one or the other of her lady friends. “She’s just doing fine now, isn’t she? Without any old college.”

Always, she spoke softly and gently. But there was nothing soft about the snatches of conversation I overheard when her friends came to call, as I bustled about, serving tea or entertaining Bailey.

“I certainly wouldn’t keep her around,” I heard one woman say. Another, eyeing my stack of textbooks on the dining room table, shook her head as I passed through.

“The black Vassar,” they called the college John D. Rockefeller had deemed worthy of funding in 1884, when he’d moved it from its basement quarters and renamed it for his abolitionist in-laws, the Spelmans.“The impudent little thing,” she said, so loudly I heard her from the kitchen. “I’ll tell you, I wouldn’t have it. No indeed. Not in my home.”

Something inside me began to harden. I watched Mrs. Hurley as carefully as she watched me, saw her nodding at the pronouncements of her friends. And I understood that in all the years when she’d talked so proudly of how she would “make something” of me, she had not imagined I would actually try to make something of myself. In her mind, I had broken a sacred trust.

Never in my life had I hidden my thoughts and feelings, but now, alone in a house where I was despised, I drew up a mask and I took care never to let it slip while in Mrs. Hurley’s presence. Only late at night, alone with my books, and in the hours I spent with six-year-old Bailey, did I feel the heaviness lift. I’d taken delight in children from the time Tom and Pete had become my little brothers, and bright and curious as Bailey was, I found no end of joy in reading to him, working with him on his letters and numbers, entertaining him by playing my French horn, and teaching him a bit of music in the process. I sang almost as badly as I played, but Bailey took no notice. We loved each other, that little boy and I. But in Mrs. Hurley’s presence I ached with a tension so overpowering that had it not been for my visits to the Wimbishes on Sunday afternoons, I doubt I could have survived.

Sundays were a feast—and not only on the food Edythe’s mother served up in heaping portions in her elegant dining room. In the home of Mrs. Maggie Wimbish gathered Atlanta’s most distinguished black citizens—lawyers, doctors, professors, educators, and clergymen like the great James Madison Nabrit, pastor of Mount Olive Baptist Church and one of the South’s most prominent black preachers. Wide as my grandmother’s reach had been in Charlotte’s black community, I’d never been exposed to a world remotely like the one in which the Wimbish family moved—one marked not only by wealth but by a deep drive for education.

Edythe’s brother, C. C. Wimbish, Jr., renowned by the late 1920s as an assistant state’s attorney in Cook County, Illinois, had earned a law degree from Northwestern University at a time when few black men reached beyond Howard University for their legal education. When Edythe and her sisters had trained as teachers at Atlanta University, they’d followed in the footsteps of their mother, one of the city’s most esteemed high school principals.

Mrs. Wimbish took me to her bosom like a daughter, and her circle of friends did as well, all of them urging upon me the care and caution required to stay alive in Atlanta. No black person—not even folk as privileged as the Wimbishes’ inner circle—could walk the streets in safety. Some years before my arrival in Atlanta, the family said, Edythe’s brother had been beaten unconscious by a group of white men and left for dead—not in a rough section of the city, but right at the edge of the elegant black neighborhood where the Wimbishes lived.

But though they warned me constantly to take care, to assume that danger lurked everywhere, to watch my back at every turn, Edythe and her friends made it clear that I must allow nothing to get in the way of my studies at Spelman. Spelman was a college that reached back to Reconstruction days, I learned from Rev. Nabrit, whose mother, Margaret Petty Nabrit, had been in the school’s first group of students in 1881. A freed slave, she’d entered as a newly married woman, along with ten others who attended class at what was then known as Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, in the basement of Friendship Baptist Church.

The pride that filled Rev. Nabrit’s voice when he told me of his mother, determined to learn to read the Bible and to write at a time when such abilities posed actual danger to her person, spoke volumes to me about the tradition of which I was a part. My anger, my bitterness toward Mrs. Hurley, my fear of the streets of Atlanta—none of that mattered, really, in comparison with what it meant to attend a place like Spelman. I made up my mind I’d finish if I died in the process.

And so I kept quiet and tread carefully in Mrs. Hurley’s home. Each afternoon, I returned to the Hurleys’ at exactly the appointed hour, saw to the serving of supper and to Bailey’s bedtime, then retreated to my room and buried myself in my textbooks for the night. I nearly ran from the house each morning, I was so eager to board the trolley that would take me to Spelman. There, inside those great iron gates that shut out a white world that loathed me for having ideas of my own, I discovered another sort of white person entirely—a person who held thinking so sacred a right that she put her very life on the line for it.

Nothing Edythe had told me about the white professors at Spelman prepared me for Mary Mae Neptune, professor of English literature, as much a warrior with her Shakespeare text and her red pen as my grandmother was with her broom. She was six feet tall, or close to it, and every bit of sixty years old, with her white hair done up in a bun, but for all her old-fashionedness, Mae Neptune was without question a revolutionary, decades ahead of her time.

What she pulled from Shakespeare’s Othello and Merchant of Venice made me squirm, at first. “The stuff of life,” she called it, but no one I knew had ever spoken so forthrightly of race hatred or interracial love. That was the stuff of pain and sadness. Only in private did people of either race refer to the shame of sexual unions between blacks and whites, even as Grandma had spoken behind closed doors to the poor outcast soul who’d earned the contempt of both races by giving birth to my foster brothers, Tom and Pete.

To train young black women to think, to hold jobs, to become leaders: that was Spelman’s mission.To hear a white woman not only speak of such things as miscegenation and racism, but to push and prod us into doing so, and in the bold light of day, stunned me. It seemed nothing was out of bounds: the pain of Shylock, the lone Jew in a Christian world; the isolation of Desdemona, despised for loving a black man.

Just what had brought a northerner like Mae Neptune to the South in the 1930s I could not imagine, and it was quite some time before I learned that her journey from her native Ohio had begun 40 years earlier when she lost the young man to whom she was engaged. His death nearly broke her, she later told me, but it also set her on some kind of quest—a quest that first led her westward, to Iowa, where she was dean of women at an Iowa university, and then to Columbia University in New York, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance.

She was a distant relative of John Brown and perhaps that, mingled with her Quaker roots, drew her to the black intellectuals of Harlem, particularly to the Atlanta University scholars who spoke of the revolution afoot in the black colleges of the South. How mightily they must have moved her, for she was a middle-aged woman when she pulled up stakes and took a position at Spelman.

“The black Vassar,” they called the college John D. Rockefeller had deemed worthy of funding in 1884, when he’d moved it from its basement quarters and renamed it for his abolitionist in-laws, the Spelmans. But for all the elegance of its magnolia- shaded campus, Spelman was a bed of insurrection and had been since its founding. To train young black women to think, to hold jobs, to become leaders: that was Spelman’s mission. And of all the professors I knew in my years there—black or white—Mae Neptune was its most fiery exponent.

Had life treated her differently, she might have been simply a well-educated farm wife with a fierce heart, or, if a professor, one who ministered to her own people in the colleges of the Midwest. But events had conspired to make of Mae Neptune something of an outsider. She was a woman uprooted by her own choice, a person who seemed to draw her strength not from the beloved family she’d left behind in Ohio nor from her colleagues on the Spelman faculty, but from bonds of the spirit.

Such a bond she forged with me. Whether she sensed from the beginning that I was in my own way an outsider—a poor working student in a sea of black privilege—I do not know. I felt, somehow, that she reached out directly to me, with her penetrating gaze and her relentless questioning. The first time she asked me to commit to a position in writing, in an essay on democracy, I felt that gaze upon me even in the privacy of my room, pushing me to say what I really thought.

Spilling out onto the paper came things I’d heard black people talk about in the quiet times, in the quiet places, when there were no white people around to hear them. And there were no white people to hear me now, for when I locked myself each night in my bedroom at the Hurleys’, I breathed as freely as if I’d actually been sitting in Miss Neptune’s classroom. Alone with my thoughts and the paper before me, I could shed the hated mask of servility I wore in Mrs. Hurley’s presence, forget the fear that suffocated me when I entered her home, forget that at any moment she might decide to throw me out and put an end to the dream of Spelman.

I forgot everything but the task before me. And I saw, as I scribbled furiously far into the night, that ever since I’d been old enough to eavesdrop on Grandma’s church ladies whispering about lynchings and Klan burnings and black men disappearing for who knew what reason, I’d been soaking up one long lesson in democracy gone wrong. I wrote as though someone had opened the floodgates, about the uneven hand of justice in the “land of the free” and the grotesque thing called “separate but equal,” putting into words thoughts I hadn’t known were mine.

__________________________________

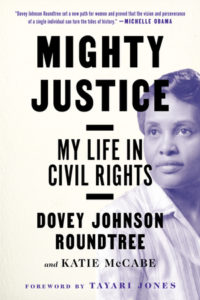

Excerpted from Mighty Justice by Dovey Johnson Roundtree and Katie McCabe. Copyright 2009, 2019 by The Dovey Johnson Roundtree Educational Trust and Katie McCabe. Excepted by permission of Algonquin Books, a division of Workman Publishing