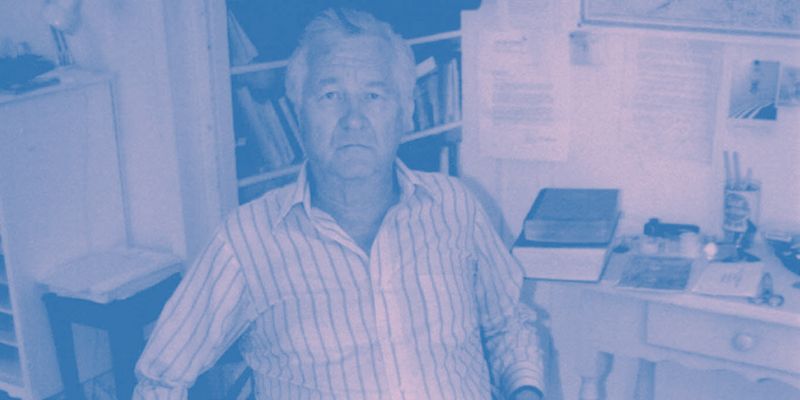

The Edge of the Abyss: William Styron at 100

Greg Cwik on the Complex, Melancholic World of Styron’s Novels

“A man is the sum of his misfortunes.”

–William Faulkner

*Article continues after advertisement

At the nadir of a particularly bad time in my life, I was escorted to Bellevue by some friends. I spent three hellacious days in a ward of anemic white gleaming harshly under sickly lights and bereft of anything resembling comfort, surrounded by people whose tethers to reality were perhaps too frayed to be repaired, rooms pervaded by the foul air of hygienic insouciance and loud with the din of minds in disarray. I arrived, clinging to my chest two books that I had, in my delirium and cashlessness, purloined just hours earlier, two life-altering books by William Styron: Lie Down in Darkness and Darkness Visible.

Lie Down in Darkness is Styron’s debut, a huge hit published when the writer was only 26; a post-Faulkner southern gothic melodrama, it concerns a family grieving themselves asunder in the wake of a young girl’s suicide. No one except for her father really wants to know why she did it; they don’t want to acknowledge their role in her too-young demise.

Darkness Visible was Styron’s final triumph, a sliver of a rumination on melancholia (the author’s preferred term for depression; the word evokes Robert Burton’s behemoth The Anatomy of Melancholy, the spiritual forebear of Styron’s book), a project born from his abrupt affliction which had him plagued with suicidal longings and dark, dark thoughts later in life, a feeling of dogged hopelessness familiar to me. The heaviness, the lightless bog, the sweet, comforting allure of oblivion… Mired in depression, happiness fades and friends disappear and the painful present grows eternal.

Styron’s disconsolate characters live in a world which is itself afflicted with melancholia, an entire existence clinically depressed.

From Lie Down in Darkness to Set This House on Fire (a disappointment in America, properly revered in Europe), Pulitzer-winner The Confessions of Nat Turner to Sophie’s Choice and Darkness Visible, Styron explores morality through emotional tumult, and not only delves into the pitiless, boundless nature of evil, but writes fervid, empathetic characters afflicted with mental and emotional maladies, very real and very human: from melancholia to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, narcissism and its kin, sociopathy; bigotry and the violence it engenders pondered as a disease of society’s collective brain and the divine interpretation of glowing hallucinations; the culturally-acceptable and deeply personal sickness of alcoholism (Styron’s lifelong consort), and always the valiant, hopeful, desperate attempts to ameliorate the burden of the broken brain and soiled soul, which, until Darkness Visible, often proved elusive for Styron’s characters—and for Styron. The struggle seems Sisyphean, a lonely impossible endeavor taken utterly alone. Sometimes you can persevere, though his characters rarely do.

Consider Styron’s use of “melancholy” as metaphor, his attributing that distinctly human feeling to non-human subjects, permeating Lie Down in Darkness like an omnipresent gloom: “In the winter, he thought, the bay would be gray and frozen, rimmed round its shore with snow, acres of frigid salt; warm inside the house, Peyton near him, they might gaze out and watch driftwood, gulls wheeling, a sky full of melancholy clouds the color of soot.” Later: “The terrace echoed to gay music, sad music, sad as a flute, and the air above, festooned with red bunting and white paper bells, was full of soft laughter and young sweet melancholy.”

And here, how he describes a person afflicted with that most woebegone of feelings: “The mood of pleasing melancholy returning, he felt very fatherly toward her, and concerned, and he once tried to prevent her from slipping, in a spasm of mirth, down the side of the wall, but at that moment her young man came up to make a laborious rescue, and then their arms about each other’s waists, the two of them weaved out of sight.”

Styron’s disconsolate characters live in a world which is itself afflicted with melancholia, an entire existence clinically depressed. Set This House on Fire largely takes place in a picturesque villa in a small, scenic Italian town perched pretty on the hills, nestled between the glory of human art and culture and the unbounded beauty of nature. The town is being used to film a movie at the same time, and the mansion, chockablock with decadence and fancy folk, serves as the setting for scenes of raucous parties (slightly redolent of the histrionics of William Gaddis’s parties, albeit tragic instead of uproarious) and the flaunting of amorality purchased at a hefty price. Styron uses “melancholy” to describe grins and greed and accuses someone of feigning melancholy in their tossed-off use of the word “dreary.” The word “suicide” appears ten times.

The novel, languorously lovely and tragic, concerns a young man, Peter Leverett, and his friend, Cass Kinsolving—who, we learn, is the drunken, inexplicable hero, tortured by his own conscious—discussing the horrors committed by a rich asshole friend of theirs, Mason Flagg, remembering the life-changing events during their ill-fated sojourn to their “friend”’s fancy Italian bastion.

Narcissism is this rich, undeniably brilliant (in that cruel, intellectual way) and undeniably appalling guy’s obvious affliction, the amorality of the affluent, with his dexterous emotional manipulation of his “buddies” (his word) and his use of faux-friends for his own wicked enjoyment, and the carefully-manufactured apologies of his. But his narcissism blossoms into violence rooted in unbridled sociopathy, the act of a brat unaccustomed to consequences, a raging superego divorced from reality and more than willing to destroy whomever to get whatever he wants.

Our unlikely hero, the wayward narrator, may be a blathering (but never belligerent) drunk, and his bibulous melancholy “profound,” but he is one of Styron’s aching artists with morals heavier than his demons; he has a big beating heart and a mind which, when not doused in booze, thrums with hard-earned intelligence. Cass is a man whose decency is contrasted with the sickness of the rich and “smart” (as Styron often does). Cass has a monologue drenched in self-loathing about his failures as a man that throbs with empathy for a man who can never be as good as he wants.

With Styron, the past and present mingle, yesterday lingering ineffaceably; the future promises no gifts. This collapse of definable time and seeping of past and present into each other, coalescing into one honest and unpleasant truth, was the impetus of The Confessions of Nat Turner, one of the great post-Absalom, Absalom! novels on race written by a white guy. In many radical ways, it eschews the literal truth of the past in pursuit of elusive larger truths. (Robert Penn Warren, one of Styron’s mentors, said that it was “a new kind of novel.”) Our narrator was told, he claims, to act by God, to commit grotesque but not unjustified violence, though we have to wonder if he was more likely suffering from the hallucinations of mental illness and malnourishment.

Cogitating on the role of violence in racial justice, he says, “…my lassitude hung on along with a feeling of somber melancholy, and I returned to Moore’s the next morning with aches and agues running up and down my limbs and with the recollection of my terrible vision lurking at the back of my brain like some unshakable grief.” It’s not easy to adequately capture the unfathomable evil of slavery with mere words, so Styron uses his familiar technique of finding the melancholy, the mental maladies, of his characters but also the worlds they inhabit, in which they are trapped, with only death offering freedom. Racism is a disease, so he meets it with hallucinations of another. He looks at the not-yet-named in the 1800s affliction of post-traumatic stress certainly suffered by all slaves, the mental anguish, the hopelessness, the manifestation of violence as a consequence.

The deeper and darker it gets, the more solipsistic depression becomes, and the less people want to help you.

In the emotionally catastrophic Sophie’s Choice, it’s not just the deeply disturbing scenes of the long-suffering Polish Catholic woman in a concentration camp that unnerve, but the scenes of that same woman, having survived the Holocaust (in body, if not soul), being emotionally abused by her vociferous boyfriend, Nathan, a labile intellectual who hates southerners and spews intense vitriol at Sophie and our narrator, Stingo. Then his mood vacillates, and he goes warm and loving suddenly, like a light switch thrown and burning the dark in a flash.

In the intimate, mundane horrors between normal people, Styron finds meaning which resounds like the clamor of a great old bell clanging, echoing, fading. (In Darkness Visible, Styron says, “The depression that engulfed me was not of the manic type—the one accompanied by euphoric highs…”) While bipolar disorder (my own inextricable problem) is not named, the novel was the first and maybe still the best depiction of the reality of the disease, The Devil and God raging inside the soul. Sophie’s Choice remains Styron’s best-known novel, but it is, sadly, now too often known by the mainstream for the film adaptation (which, Rachel says in Friends, is “only Ok,” a bit too generous, as it is one of the great Alan J. Pakula’s worst films, and marks the beginning of Meryl Streep acting too loudly). Styron’s literary style cannot be faithfully and fully translated into moving images.

It often goes unmentioned that mental illness is the co-villain of the novel, arguably as torturous and insoluble as the Third Reich. Styron describes inanimate objects as melancholic and behaving melancholically, as he does both Sophie and Stingo (a young, naive aspiring writer from the south, like Styron), characters individually tragic and catastrophic when inevitably paired together, bonded in life and death.

Schizophrenia is used by Nazis to describe the Jewish persuasion, and also by Styron as a way of describing the Nazi influence on the world, and what the Holocaust says about the mentality of people. Nathan is a genius, and in the wild dark of his affliction more simpatico with this sick, sad world than Stingo is, more than any of Stingo’s characters conjured from even the darkest doldrums of his imagination. The word “suicide” is used almost 20 times in the novel, the final time in the phrase “suicide pact,” quotation marks Styron’s.

When life has lost its appeal, when the simple, quotidian actions of everyday unamazing existence have grown too heavy and cumbrous, when you cease to matter (if you ever did) and the musings of melancholic solipsism begin to make sense, you have to find solace in something, or at least feel like there might be even the tiniest vestigial scrap of hope you can grab. Sometimes it’s writing, as with Stingo, or painting, like Cass; sometimes that reason evades you. Styron himself stood stalwart against his disease, though he could not totally vanquish it. He was hospitalized several more times after Darkness Visible came out in 1990, including a half-dozen hospitalizations between August 2003 and October of 2004, twenty-five months before he died at 81. (Interestingly, his doctor at the time, Alice Flaherty, was working on a book about her hypergraphia, an addiction to writing, while Styron himself was suffering from the antipodal, hypographia; his depression effectively ended his career as a novelist.)

In Darkness Visible, Styron astutely and eloquently captures the sense of alienation that accompanies severe depression, the most awful quality of which is not just the beckoning of oblivion, or the expunging of hope, or the somatic pain galvanized from the pain of the intangible, but the way no one seems to understand. “It’s quite natural that the people closest to suicide victims so frequently and feverishly hasten to disclaim the truth; the sense of implication, of personal guilt—the idea that one might have prevented the act if one had taken certain precautions, had somehow behaved differently—is perhaps inevitable.

Even so, the sufferer—whether he has actually killed himself or attempted to do so, or merely expressed threats—is often, through denial on the part of others, unjustly made to appear a wrongdoer.” The deeper and darker it gets, the more solipsistic depression becomes, and the less people want to help you. In his short, post-Darkness essay “Interior Pain,” he further elucidates that “the almost uniquely interior nature of the pain of depression, a pain that is all but indescribable, and therefore to everyone but the sufferer almost meaningless.”

In his last published book of fiction, A Tidewater Morning, comprising three autobiographical novellas written in a far simpler style than the virtuosity of his novels, Styron begins the last paragraph of the title story: “We each devise our means of escape from the intolerable. Sometimes we can fantasize it out of existence. I recall repeating in bewilderment the words he commanded me to say—‘Yet alone shall I prevail!’—while my mind composed such other words as would distract me from the moment’s anguish.” Being alone, Styron knew, is an intrinsic part of life to which few are immune, a universal agony of the heart and spirit. As Cass says in Set This House on Fire, “…maybe in order to think straight a man just needed to be dragged, every now and then, to the edge of the abyss.”

Greg Cwik

Greg Cwik has written for Reverse Shot, MUBI Notebook, Slant, The Brooklyn Rail, Vulture, and elsewhere.