The Early Career of a New York

Yankee Icon

On Yogi Berra's Journey from Rookie to Ten-Time Championship Winner

If 1946 was when Americans took a deep breath after ten years of the Great Depression and six years of the Second World War, 1947 is a time of great opportunity and optimism. Fueled by the GI Bill, which gives 16 million veterans low-interest loans for college tuition, buying farms, and building new homes, the nation’s first true middle class begins to emerge and flourish. America’s birthrate—held back for more than a decade—begins to take off. So do the new parents, who migrate to suburbs now beginning to develop outside the nation’s major cities.

America is further transformed as farmworkers leave their rural roots for better opportunities in towns and cities. Wages rise and jobs are added as captains of industry struggle to keep pace with demand for their goods. In place of matériel and machines for war, American factories are churning out shoes and clothes, washing machines and ovens, cars and pickup trucks. And for those few who can afford the newest in technology, televisions and air conditioners.

Though there are but 9,000 television sets in the United States in 1947, the broadcast industry will grow quickly and change the country’s culture forever. On January 6, President Harry Truman gives the first televised State of the Union address. Meet the Press—a news program destined to become television’s longest-running show—brings politicians and power brokers into America’s living rooms. Howdy Doody, starring a large puppet dressed as a cowboy, holds children spellbound for 30 minutes each day. Interest in Howdy is so great it creates a whole new industry—toys based on television characters.

With their favorite ballplayers back from military service and a little extra money in their pockets, Americans turn to baseball in record numbers. It’s hard to overstate baseball’s popularity in this rapidly changing country. Opening Day and the midsummer All-Star Game—the latter conceived as a way to bring in fans during the depths of the Depression—are undeclared national holidays. The World Series is just about the only thing Americans talk about for nearly two weeks every fall.

The game has become such a melting pot—the very symbol of America’s identity—that the son of Italian immigrants is the game’s most popular and admired player. And in the spring of 1947, an African-American will play what is considered a white man’s sport even as segregation remains the law of the land throughout the South. It’s still more than a decade before the Civil Rights movement truly takes hold, but many more black players will follow Jackie Robinson into the major leagues soon after the Dodger infielder’s Rookie of the Year season.

With their favorite ballplayers back from military service and a little extra money in their pockets, Americans turn to baseball in record numbers.

As important as Robinson becomes, the national pastime in 1947 is still very much Joe DiMaggio’s kingdom. He’s recognized by media and fans alike as the best to ever play the game, and that’s been true almost from the first day he pulled on a Yankee uniform in 1936 at the tender age of 21. No player has ever put up the numbers—219 home runs, 930 RBI, a .336 batting average—that DiMaggio did in his first seven seasons. The Yankees won a record four consecutive World Series in Joltin’ Joe’s first four seasons, adding two more pennants and another World Series in the next three seasons before he left baseball at 27 for three years of military service in World War II.

But DiMaggio is far more than numbers. He’s the very embodiment of the Yankee Way: excellence, tradition, and class. He is a true American hero, as elegant and graceful off the field as he is on it, so popular he can’t walk down the street without being mobbed by fans begging for an autograph or hoping to get close enough just to touch his sleeve. Forever withdrawn and distant, he is memorialized by songwriters in pop tunes, and newspapers can’t write enough about him. Ernest Hemingway, one of his few real friends, makes DiMaggio a central figure in his Pulitzer Prize–winning novella, The Old Man and the Sea.

In mid-February of 1947, as rookie catcher Yogi Berra and the rest of the New York Yankees gather at LaGuardia Field in the early morning hours to depart for a four-week, three-country tour of the Caribbean, there is no man more famous in America than Joe DiMaggio. But as Berra climbs aboard the chartered twin-engine plane for the 1,600-mile flight to San Juan, Puerto Rico, the trip’s first stop, he can see DiMaggio is clearly unhappy. And worried—the offseason operation to remove the painful bone spur in his left heel shows no sign of healing.

And that means all of Berra’s new teammates are worried, too.

*

As the Yankees settle into their first week of work in San Juan, there are two stories that dwarf all others. One centers on the absence of DiMaggio, who after three days has yet to emerge from his hotel room, much less interact with his teammates working out for new manager Bucky Harris across the street at Sixto Escobar Stadium. The only person who sees DiMaggio is Mal Stevens, the doctor whose sole responsibility is to tend to the team’s most important player.

The other story line is the team’s rookie catcher. Yankee veterans and the media aren’t quite sure what to make of this kid, but Berra’s excitement at simply being in the major leagues is ever-present and endearing. No two players could have more different stories to tell.

Yankee veterans and the media aren’t quite sure what to make of this kid, but Berra’s excitement at simply being in the major leagues is ever-present and endearing.

DiMaggio is livid with team President Larry MacPhail for forcing him to make this trip just five weeks after doctors removed a three-inch bone spur from his heel. He knows MacPhail is strapped for cash and booked this tour to help pay off loans from his two millionaire co-owners—but DiMaggio doesn’t give a damn. He doesn’t like MacPhail and hates that the Irishman is using him as a gate attraction when he should be back in New York recuperating.

The spur was discovered a few months ago when DiMaggio complained of pain in his heel while doctors were examining Joe’s left knee and ankle, which he injured last season. The operation left a five-and-a-half-inch incision that has refused to heal, and Dr. Stevens spends each day in San Juan slicing away dead skin on Joe’s wound and battling a stubborn infection. At 32, DiMaggio is wondering if his career is nearing an end.

That’s the question Harris and his players keep hearing before and after each of their workouts in the San Juan sun. Playing with Joe has always had its pros and cons, though his teammates—who hold DiMaggio in nothing short of awe—insist the former vastly outweigh the latter. They see DiMaggio demanding perfection from himself on every play, so they attempt to do the same, becoming better players in the process.

Joyful clubhouse chatter usually accompanies winning, but the Yankee clubhouse is serious and somber, just like the man who dominates the room while rarely saying a word. Win or lose, DiMaggio spends each postgame tucked into his locker, sipping his cup of coffee, dragging on his cigarette, slowly unwinding from the self-imposed pressure. No one celebrates unless Joe does, and that doesn’t happen often.

But all this might change this season, for there is nothing somber about Yogi Berra, who within days of the team’s first workout has captured the imagination and hearts of his manager, his teammates, and especially the press. While DiMaggio feels the burden of perfection, Yogi exudes the joy of playing a game. He’s the kid who just can’t stop smiling, and his teammates find themselves smiling, too—especially with Joe nowhere to be seen.

There is nothing somber about Yogi Berra, who within days of the team’s first workout has captured the imagination and hearts of his manager, his teammates, and especially the press.

And it’s quickly apparent that the kid can play, at least when he has a bat in his hands. Berra, 185 pounds of muscle packed onto a five-foot-eight frame, is still a work in progress behind the plate—“He fields with his bat,” writes Dick Young of the New York Daily News—but everyone’s taking notice of his booming line drives. “He is one of the hardest-hitting rookies I have ever seen,” Harris tells the writers after each day’s workout.

Then there’s what often happens when Yogi opens his mouth. His twisted English and goofy tone give Yankee reporters their first true character to write about since the days of the Babe and his off-the-field antics. “Berra has easily made himself the standout personality in camp,” writes the New York Times’ John Drebinger, dean of the nation’s baseball writers, who won’t get used to calling the rookie Yogi until late in the season. “Larry exudes good cheer and enthusiasm at every turn.”

As much as they all like Berra, neither his manager and teammates nor the media can resist mocking the way he looks, the way he sounds, the trouble he has putting words to his thoughts—even the comic books he reads and shares with many of his teammates. Everything is fair game: his large nose, heavy eyebrows, and dark, leathery skin; his thick neck, almost lost between his oversized shoulders; his low, guttural voice. Names like Nature Boy, Quasimodo, and the Ape are quickly finding their way into what Berra hears from teammates and reporters alike.

Yogi accepts the teasing from teammates with his wide, gap-toothed smile, figuring they wouldn’t bother with him if he wasn’t good enough to be worthy of their attention. And he still remembers the advice of his old minor league manager Shaky Kain: any protests would only increase the number of insults thrown his way. As for the media, well, it’s not like Berra hasn’t heard it all before. Besides, he tells one reporter, “I haven’t seen anyone who hits with their face.” It’s a line every writer will repeat for years.

Yogi accepts the teasing from teammates with his wide, gap-toothed smile, figuring they wouldn’t bother with him if he wasn’t good enough to be worthy of their attention.

The fascination with Berra is interrupted just twice. The first time comes five days into this trip when DiMaggio finally leaves the hotel. He receives a police escort through the mob of fans as he walks across the street and enters the stadium. But he doesn’t play. DiMaggio takes a seat next to the team’s dugout, suns himself, and returns to his hotel room.

The second is far gloomier. On February 25, MacPhail announces DiMaggio will be leaving Yankee camp and flying to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where they’ll try skin graft surgery in hopes of closing the wound in his heel—and saving the superstar’s season. Joe D has missed the first game of the season four of his eight years with the Yankees, so everyone is asking Dr. Stevens the same question: will DiMaggio be ready for Opening Day in Washington, on April 14?

Stevens has no answer.

The man tasked with building the Yankee lineup without its best player does not lack experience. Bucky Harris was the “Boy Wonder” second baseman and manager who led the Washington Senators to their first and only World Series title in 1924, at the age of 27. He managed mostly middling-to-poor teams in four cities over the next 20 years. Last season he was the general manager of the International League’s team in Buffalo, where he watched a chunky little catcher called Yogi manhandle his pitching staff. MacPhail brought Harris aboard as a special assistant early last September, then named him the Yankees’ 10th manager two months later.

Now 50, the lean, five-foot-nine Harris still retains his boyish good looks and his friendly, easygoing demeanor. He knows the measure of any Yankee manager is Joe McCarthy, who won seven World Series titles in his 16-year run with this franchise. McCarthy put the bar high—anything less than a title is now considered a failure.

Harris has already developed an easy rapport with the beat writers, who are instrumental to any New York manager’s success. In 1947, newspapers are still the dominant form of media, and a writer assigned to cover baseball is immediately one of his paper’s biggest stars—especially in baseball-mad New York, home to three of the game’s 16 teams.

The eight writers who flew with the Yankees to San Juan are almost all veterans with upwards of 20 years or more on the beat.

These are the men who shape the way New Yorkers think about any Yankee manager and player, even the Big Dago, who was stung when the writers turned on him during his 1938 contract dispute. There are almost eight million people living in New York City’s five boroughs, and at least two million of them read the New York Daily News and its Yankee writer Joe Trimble. That’s the man Bucky Harris is talking with at a San Juan bar the day DiMaggio leaves camp.

“Did you see the Ape hit that ball today?” says Harris, talking about yet another day of Berra blasting the ball all over Sixto Escobar Stadium. Harris understands ridicule is part of the game—indeed, there’s at least one player on every team whose job it is to rattle opposing players. But Berra, still a few months shy of 22, is taking so much abuse Harris has quietly asked the writers to tone it down. Yet even Bucky slips into insults when Trimble asks him who’s going to bat fourth if DiMaggio isn’t ready by Opening Day.

“Do you think the Ape could do it?” Harris says, real excitement in his voice. “I bet he could if he didn’t get scared.”

Actually, Harris is thinking about more than Berra batting cleanup, though he’s not ready to share his thoughts with the media. Who knows if DiMaggio will make it back or how good he’ll be if and when he returns? And age hangs heavy on this roster: DiMaggio’s outfielder running mates Tommy Henrich, the team’s next-best player, just turned 34, and Charlie Keller, who led the team with 30 home runs and 101 RBI last season, will be 31 in September. Spud Chandler, his best pitcher, is 39.

Yes, Harris thinks, Berra has a big future ahead of him. Just not behind the plate. At least not yet.

Berra’s Newark teammate Bobby Brown is also having a strong spring, and young pitchers Don Johnson and Spec Shea look like they will probably help. But it’s Berra whom Harris thinks he can build around. Yogi’s powerful left-handed swing is tailor-made for Yankee Stadium. And Harris is sure the fans will love this kid in a way they will never love DiMaggio. They’ll see his odd-shaped body and his constant smile, and they’ll pull for him when he makes a mistake and cheer for him when he smacks the winning hit.

Yes, Harris thinks, Berra has a big future ahead of him. Just not behind the plate. At least not yet.

*

“Stand at a slight angle when there’s a right-handed hitter at the plate,” Joe Medwick says. “That way you can see if the ball is going to slice toward the foul line.”

Medwick is talking to Yogi Berra, the same kid who used to sell him newspapers back in St. Louis when they were both so much younger. It’s the first week of March, and the Yankees are in Caracas, Venezuela, for nine days before wrapping up their tour of Latin America with three days in Havana. Bucky Harris had pulled Berra aside soon after they arrived in Caracas and said he was giving Yogi a shot in right field until he learns how to play catcher on this level. And he’s asked Medwick, now 35 and finishing out his Hall of Fame career, to be Berra’s guide.

So Medwick, a ten-time All-Star for the Cardinals, Dodgers, and Giants, has spent the last few days teaching Berra how to get a jump on a line drive. He instructs Yogi how to play the ball off the wall and set himself before he throws, and how to quickly find the cutoff man for relays back to the infield. He even shows him the right way to flip down his sunglasses without losing track of the ball.

The early results are encouraging. Berra hits a home run in his first game as a right fielder against a local team, then hits three doubles and just misses making a spectacular diving catch in the first of a three-game set against the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were training in Cuba and also touring Latin America. Berra’s route to a fly ball is often circuitous, but he is fast enough to make up for it and his arm’s strong enough to keep opposing runners honest.

Harris uses Berra behind the plate in batting practice but grows more comfortable with the idea of Yogi playing right field as the Yankees finish up their Latin American tour and fly to spring training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida, on March 11. It’s the same day DiMaggio has a skin graft, and with catchers Aaron Robinson and rookie Ralph Houk performing well, Harris keeps playing Berra in the outfield.

Best of all: Berra continues to hit. By the time the Yankees are ready to break camp and board their train for the trip north, Berra has hit safely in 14 straight games. “The amazing Yogi continues to astound his skipper more and more with each succeeding day,” the New York Times’ Drebinger writes after Berra has yet another big day. “Blasting him out of that Yankee outfield is going to be no simple task, even after DiMaggio returns to center.” The new Yankee manager, Drebinger says, “takes a deep and pardonable pride in the chunky little Yogi who, under the cover of a series of night games in Caracas, was converted from a catcher into a surprisingly fine right fielder.”

Not everything written and said about Yogi is positive. Five other teams have their camps in the St. Pete area, and opposing players all take turns taunting Berra. During one game with the Cardinals, outfielder Enos Slaughter—a player Yogi rooted for as a teenager—tells him his face looks like he’s been hit with the back of a shovel.

“You’re the only player who looks better with his mask on,” cracks Slaughter.

That line makes its way to every camp. So does the habit of throwing a banana on the field when Yogi walks up to the plate. As rookie initiations go, Berra sees his will be a tough one.

Yogi lets the insults bounce off him—all but one. It was delivered in the form of a question by Rud Rennie of the New York Herald Tribune. “You’re not really thinking about keeping him, are you?” Rennie asks Harris. “He doesn’t even look like a Yankee.”

That one stung, but Berra is soothed when Harris tells a group of writers the Yankees are indeed going to keep Yogi. And then Harris goes one step further.

“I’ll make a prediction about Yogi,” Harris says. “I say within a few years he will be the most popular player on the Yankees since Babe Ruth. I know that Henrich and Rizzuto and DiMaggio have a lot of fans that admire them. They are great ballplayers. But I mean more than that. He’s funny to look at and sometimes he makes ridiculous plays. But he has personality and color. That’s crowd appeal and it makes people pay their way into the ballpark to see him.

“And don’t think he’s a dope. Try to remember that he hasn’t had much schooling and it is a disadvantage in conversation.

“Just don’t sell him short when he is up there at the plate. He’s going to kill a few people with that bat and they won’t think he’s funny at all.”

Berra does little to prove Harris wrong in the team’s two stops on their way to New York. Yogi blasts a pair of home runs, a double, and two singles, and drives in five runs as the Yankees demolish the minor league Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association on April 6. A day later, Yogi drives in six runs with a home run, double, and single against his old Norfolk Tars. The home run flew over a high wall, 450 feet away in dead center field. Everyone in the park stood and applauded, save for the Yankees, who have been reacting to Yogi’s increasing production with timeworn rookie hazing: sitting in the dugout and giving him the silent treatment.

It’s obvious to all they’ll have plenty of time to talk to this Berra kid this season.

__________________________________

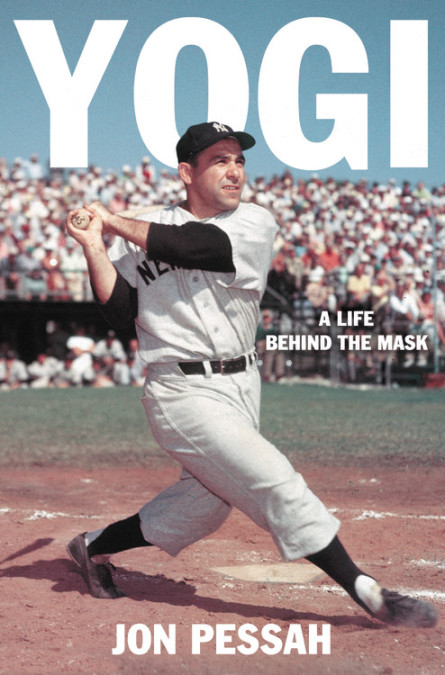

Excerpted from Yogi: A Life Behind the Mask by Jon Pessah. Copyright © 2020 by Jon Pessah. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Little, Brown.

Jon Pessah

Jon Pessah is The New York Times bestselling author of The Game, a critically-acclaimed examination of the power brokers who built the major league baseball into a multi-billion dollar business. A founding editor of ESPN the Magazine, where he ran the investigative team, Pessah has also managed the sports departments for Newsday and the Hartford Courant.