The Dry-Eyed Mourning of Gary Indiana

Sarah Nicole Prickett on Indiana's Novel Gone Tomorrow

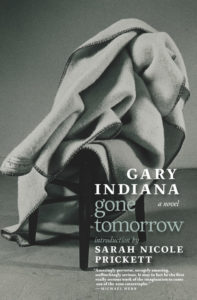

The copy of Gone Tomorrow I wanted was a hardcover listed on Amazon as a “1993 Gay Signed First Edition,” printed in England by Pantheon, but it cost 40 dollars plus shipping. The one I ordered was an American paperback, which had an apter name on the spine—High Risk Books—and an equally suitable price of three dollars and 99 cents. Three days later it came as advertised, in very good condition. No signs appeared of a former owner. Pages were unbent, words were neither underlined nor highlighted, and nothing was written in the margins until the end of the second-last chapter, minutes from close.

Here the dying subject, an art-house director—Paul Grosvenor—who has been diagnosed with HIV, gets groceries with the unnamed narrator, a quondam young actor, on the last day they will be together. Like most of the novel, the scene is told from memory during the course of an unplanned long afternoon the narrator spends with another man, Robert, a mutual friend last seen at the funeral. He recalls going with Paul into the corner grocery, a mom-and-pop store. Paul took a shopping basket and began tearing through the place. He threw in a bottle of orange juice, then a bottle of grapefruit juice, a six-pack of Heineken, a jug of cranberry juice. Cheese. Cheddar cheese, brie cheese, blue cheese, provolone. Sweet Italian sausage. Hot Italian sausage. More cheese. A head of lettuce. A dozen eggs.

What is the rush? A staving off. Enough is in the cart for Babette’s dinner and Leopold Bloom’s breakfast. Only, Paul is not hungry. He’s desperate, filling time with the wan hope of more time.

At the bottom of the page a reader has jotted, in black gel ink newer than the paper, a neat seven words. Graphologists examining the words would say that the annotator was a thwarted idealist, with a tendency toward sarcasm and anomie, in love with ambivalence; that he was regressive, fixated on ideas, modest and economical and at the same spontaneous, with a sharpened wit. Scholars would just look at the words:

And daytime is / The loss of this

The couplet is from a poem on something momentary:

This like a dream

Keeps other time,

And daytime is

The loss of this;

For time is inches

And the heart’s changes,

Where ghost has haunted,

Lost and wanted.

The poem is by W.H. Auden. I would not have thought to compare Indiana with him, or to compare their works, not least because he—the poet—was fashionable in his time: No young person was brighter for a while. Auden in my mind remained wan and soignée and always reminiscing, definitively a “hopeless romantic.” Indiana by contrast was brilliant and inimical with style in excess of taste, as a sentence from a random page in Gone Tomorrow illustrates: “Somewhere between the moon and the villa a cloud shaped like a long, poisonous turd hovers in the balmy air, blue as a fatal contusion.”

“What is the rush? A staving off. Enough is in the cart for Babette’s dinner and Leopold Bloom’s breakfast. Only, Paul is not hungry. He’s desperate, filling time with the wan hope of more time.”But Auden in truth was more like a funny gay pessimist. Biographies skimmed reveal a wry sense of danger, a glimmering mordancy, the occasional attraction to murderers, wicked jokes. Anachronistically “open” about his sex life, he yet refused to “accept” himself as he was, was too neurotic and at the same time too Christian for that; he took care to seem more self-centered, indifferent, and aloof than he was intimately known to be, using effete aesthetics to obscure his severe and constitutive morality. Auden, when he wasn’t mooning, appeared as his own negative image. He was variable, too. He lived to reject as stupid or wrong his old verses, but forgot (or was it forgetting?) to deny what he’d famously said early on, that all his poems concerned love.

In Gone Tomorrow the motives and ends are both ulterior, the plotting kairotic. Paul, a cipher for Dieter Schidor (to whom the book is dedicated), begins making a film so experimental that the script is unfinished at shooting time in Bogotá, Columbia. Under the posthumous influence of a Low German auteur à la Fassbinder, he travels and works with a sybaritic entourage led by a translator whose name—Valentina Vogel—rings predictively of Veronika Voss. His ambition is fateful. Starring in the film is Irma, a rusty sexpot who effumes the “silvery illusion of perverse insatiability.” Opposite her is Michael, an unknown whose “southern beauty” is “so extreme that it … rip[s off] the veneer of civilization,” which is to say he looks like the girl in Joseph Conrad’s Victory. (That Indiana and Joan Didion have the same favorite Conrad novel makes sense. He likes to trace, as she does but less overtly, less permanently, the journey Heyst takes away from the world and from the self which exists because of others, and to linger on the eve of sure disaster.)

The narrator, whose part seems minor, watches the leads rehearse a sex scene. “Between them is developing the possibility of murder,” says Paul. “Between their characters,” the narrator tries to clarify, but the working definition of love is already clear. Locals say a serial killer is loose in Bogotá. Dinner is interrupted by the most erotic cockroach since the one in Clarice Lispector’s maid’s room. A situationist orgy among friends concludes the first act, and the second, where love is made on acid at Dachau and men die at home, makes as sharp a veer on paper as that between the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany.

“The narrator, whose part seems minor, watches the leads rehearse a sex scene. “Between them is developing the possibility of murder,” says Paul. “Between their characters,” the narrator tries to clarify, but the working definition of love is already clear.”Indiana once, in an essay on Brecht and Weill’s opera, The City of Mahoganny, found it “possible to view the entire Weimar period. . . as one of reprieve—a long one, relatively speaking, that produced an immense outpouring of creative work,” which he likens to the time of cheap rent in a post-Robert Moses, pre-Donald Trump Manhattan, i.e. the mid-60s to early 80s. Sarah Schulman, in her decade-old polemic The Gentrification of The Mind, remembers the critic Michael Bronski saying, at a conference on “AIDS literature” in 1998, that if it weren’t for fear of the homo it would be “American literature.” With Schulman, it’s possible to imagine a world where Indiana is as American as John Knowles (and only slightly more homosexual). Indiana, who is from New Hampshire the way Conrad is from Poland, may not want to be that American: He belongs to literature, purely. But, like Schulman, he dreads progressive memory loss, the encroachment of normalcy that passes for understanding. By the end of Gone Tomorrow the narrator, valiantly combating the effects of alcohol, is thinking,

It was a real effort not to become histrionic, sentimental. [Robert and I] were two men who did not know each other very well, both in early middle age, making pleasant masks for each other in the starlit dreamtime of the Chelsea roof, while all around us the world we had known all our lives moved inexorably toward a gray homogenized blankness.

Indiana’s dry-eyed mourning evinces zero gratitude for being left alive. Paul, stricken with the plague before it has a name, let alone a cure, tries to kill himself with the soft, slow grandeur of a virgin on her wedding night, only to wake in the hospital with brain damage and parents in denial. There is nothing more absurd or redundant, tragic or farcical than the sick concatenation of “failed suicide attempt.” (When Auden’s Icarus falls into the sea, a distant spectator thinks it is “not an important failure.”) There is something ennobling about it too. There is something historically queer. Like writing a novel too weird and perverted and frankly minacious to stay in print, too unforgettable not to be reissued.

It was around the time this novel came out that Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, introducing her essay collection Tendencies, uneasily observed a culture’s rising fascination with gayness. “In the short-shelf-life American marketplace of images,” said Sedgwick, “maybe the queer moment, if it’s here today, will for that very reason be gone tomorrow.” Then she identified the point of literature, for those who are queer and those who—more unfortunate—are human: “to make, stubbornly, a counterclaim against that obsolescence.”

__________________________________

From Gone Tomorrow. Courtesy of Seven Stories Press. Copyright 2018 by Gary Indiana. Introduction copyright 2018 by Sarah Nicole Prickett.

Previous Article

MFA vs. Everything:Four Writers Weigh In