The Diving Suit and the Bathtub, or: How a Single Image Sparked a Whole Novel

Steve Stern on the Haphazard Affair of Writing a Book

Sometimes it starts with a single image. Mine was a guy in an old-fashioned diving suit walking along the bottom of a river, pulling another guy seated in a bathtub on the river’s surface. The image came to me unbidden, and it was weird enough to leave a lasting impression. So I filed it away in the catalog of weird impressions that writers (this one anyway) keep for future reference, and promptly forgot all about it.

Years ago, while visiting the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, I encountered a series of paintings that seemed to me to be a kind of perfect marriage between the beautiful and the grotesque. The portraits were distorted to the point of caricature, the landscapes as if caught up in hurricanes, still lifes of slaughtered animals that seemed to be refusing to give up their souls. I was awed by their energy, spellbound by their visionary sensibility and their ferocious storms of color. They were the work of Chaim Soutine, an artist I had not previously been aware of. In his book Shocking Paris, about a circle of immigrant artists in the early 20th century known as the School of Paris, Stanley Meisler described Soutine as an unwashed, unlearned, misanthropic, practically barbaric genius from an impoverished East European shtetl. The book recounted something of his tumultuous exploits among the bohemians of the Montparnasse art scene, back when Paris was the capital of the cultural universe. It was a time and place that fired my imagination, and Soutine, the consummate misfit, struck me as a character after my own heart, and ready-made for translating from real life into fiction.

I wanted urgently to tell his story, but not as a factual biography—rather as a tale informed by the sort of fabulous dimension that such a savage character deserved, and that I felt only a novel could endow. Nor did I think the story should be confined to a strictly linear narrative; it should be as fluid and mercurial as the figures in Chaim’s paintings. In them he subverted ordinary reality and ignored the bounds of naturalism, conferring his people, places, and things with an aura of timelessness. I would aspire to that same quality in relating his story. It was at that point in my thinking that an odd thing happened: the image of the guy in the diving suit resurfaced in my mind, and this time I identified him as the artist Chaim Soutine. He was, I imagined, trudging along the bottom of the River Seine, hauling a bathtub in which his friend and mentor Amedeo Modigliani sat happily afloat.

I imagined that Modi, as he was known to his friends—Modi, the handsome and cultured prince of the bohemians, diametrical opposite of his grungy pal Soutine—had organized a boat race. The major artists of the day (and also, as it turned out, of the modern era) would construct a fleet of makeshift crafts to sail in competition on the Seine. The event would be a grand diversion from the hardships of daily life in Paris during the First World War. And Modi would give his own vessel, a smut-blighted porcelain bathtub, a secret advantage; for he had persuaded the young Soutine to overcome his hydrophobia and pull the tub from below the surface of the river.

I wanted urgently to tell his story, but not as a factual biography—rather as a tale informed by the sort of fabulous dimension that such a savage character deserved, and that I felt only a novel could endow.

So the boat race would be the frame for my book. Chaim’s underwater odyssey would provide the natural setting in which he could recall the entire arc of his life. But how recall things that have yet to happen? The year was 1917 and Chaim would not die (painfully, I’m afraid, of a perforated ulcer) until 1943. The dilemma stirred an echo in my mind: an amateur folklorist, I remembered the Jewish folk legend of the angel of forgetfulness, which Chaim would also have heard in his shtetl childhood. In the legend the angel that watches over the child in the womb reveals to it—along with the history of the world from beginning to end—the whole of the life the child will live. Then, upon birth, for reasons known only in heaven, the angel tweaks the child under the nose (hence the indentation called the filtrum) and the newborn forgets everything they have learned. It occurred to me that Chaim in the scaphandre, the diving suit, with its umbilical connection to a portable respirator dragged along the riverbank by a hired boatman, was much like that child in the womb. In the scaphandre he becomes both witness to and participant in his own revealed experience from birth to death. But in keeping with the protean nature of time in Chaim’s submarine element, the narrative should unfold in a seemingly haphazard fashion; scenes would transpire according to their aesthetic and dramatic import rather than in chronological order. That way a reader would have the impression that everything in Chaim’s life (including his death) is happening at once. This was my hope at any rate: that all would be perceived as taking place on a single spring day in the midst of a zany artists’ regatta, while the planet reeled from a bloody war that would transform history.

At the end of the book, just after Chaim has suffered his own cruel demise, he is yanked from the Seine by a triumphant Modigliani. He’s released from the confinement of the diving suit, informed that he is responsible for Modi’s victory in the boat race, and reintroduced to the world at large. The scene gives the sense, again hopefully, of a virtual rebirth. And like the newborn child tapped under the nose by the angel, Chaim has forgotten all he’s seen and endured at the bottom of the river. Unconscious of but deepened by the breadth of experience he’s confronted in the scaphandre, Chaim is free to shape his own future; he is poised to commence afresh the tragi-comic saga of his extraordinary life.

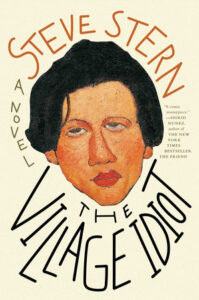

Looking back, it strikes me that writing a novel is finally a haphazard affair. You take an image here, a passion there, a fixation, an obsession, a memory, distill it all in the alchemical alembic of your imagination, and hope—that word again—that the end result is, if not the philosopher’s stone, at least some kind of enchantment, a compelling story. So now you know something about how novels get written, or anyway somewhat fanciful novels like mine. The book is called, incidentally, The Village Idiot.

____________________________

The Village Idiot by Steve Stern is available now via Melville House.

Steve Stern

Steve Stern, winner of the National Jewish Book Award, is the author of The Pinch, a novel which will be published by Graywolf Press on June 2, as well as several previous novels and story collections, including The Book of Mischief and The Frozen Rabbi. A Memphis native, he now teaches at Skidmore College in upstate New York.