The Devastating Fallout of Addiction and Corporate Burnout

Eilene Zimmerman on Burying Her Husband

Now here we are, with poignant speeches, funny stories, even music. Anna has prepared an emotionally wrenching a capella version of “Blackbird,” the only Beatles song her late father ever liked. Last night, when the kids and I were rehearsing our speeches, Anna said she wished we didn’t have to do this right now.

“I know,” I said. “I wish we didn’t have to either. But the people Dad worked with, and Grandma and Grandpa and the rest of the family, want this service too. This isn’t for us. This is for everyone else. Like putting on a play.” And it is, absurdly, like theatre. What I would really like to say to the audience is “I can clear this up for all of you in five minutes, so you can stop asking for details about what happened and why.” But I don’t—we don’t—because we are afraid to tell anyone the truth. It feels to me that Peter’s firm is tiptoeing around the circumstances of his death, and that makes me fear telling the truth to anyone beyond a very small circle of friends and family. I know Wilson Sonsini sent a firm-wide email notifying its employees about Peter’s death, posted a note about it on the firm’s website, and took down Peter’s attorney profile. But I have no idea who there, other than Jeff, knows how he really died.

It could be no one he worked with suspected anything was seriously wrong with Peter, although the needle caps, tourniquet, and alcohol wipes in his work bag suggest he was shooting up in the office. Today, however, is not about conjecture. It’s about memorializing. And I will do what I’ve been asked to do: provide closure. I have orchestrated today’s careful performance in which Peter will be canonized. And then everyone at his firm can get back to billing hours.

Matt, an associate who worked for Peter, comes up to the front of the room and takes the microphone. He has been so shaken by his boss’s sudden death he can barely speak, and tears run down his cheeks as he talks about Peter as a mentor and friend. I look around the room to see how his co-workers are taking this heartbreaking display and am stunned. The room is packed and there is a winding staircase that leads to an upper floor where people who did not get seats are standing. Many of them are staring at their phones. They are reading texts and emails, perhaps even reviewing documents on those tiny screens; some of them are actually thumb-typing. Quite a few of those sitting in the back have their heads bent toward their laps, hands clearly cradling phones. Their colleague and friend is dead—for all they know from working too hard—and they can’t stop working long enough to listen to what is being said about him.

It’s possible that this is how they are coping with the unexpected death of their 51-year-old colleague. Research from Larry Richard, an organizational psychologist, former attorney and founder of LawyerBrain, a consultancy that uses data about the personalities of lawyers to enhance their performance, shows that in general, lawyers are hooked on intellectual validation—that little shot of dopamine they get every time they solve a client’s problem. Dopamine makes us feel better; being needed by someone, even a client, makes us feel important. Maybe the attorneys here believe being needed will act as a hedge against their own mortality. How can you die if your clients are emailing you requests for opinion letters and document reviews? How can you die if you have a conference call on your calendar that afternoon? But, of course, you can.

When you’re dying, I wondered, who do you call? Peter dialed in to a conference call.

When I took Peter’s phone off of his bed, I looked at the call history to see the last person with whom he spoke. When you’re dying, I wondered, who do you call? Peter dialed in to a conference call.

I phoned the number to identify it and found it was a conference line, the kind of number you dial and then are prompted to enter a pin number, after which you are connected to others in the conference. The last call of Peter’s life wasn’t to his kids, me, his parents, a friend, even one of his dealers. Peter—drifting in and out of consciousness and barely able to sit up—had dialed in to a work call.

He very nearly predicted this would happen. Right before Peter became a partner at Wilson, when we were still married, he told me he couldn’t see himself working this intensely long-term. “I can’t do this for the next twenty years,” he said. “I can’t physically do it.”

Dysfunctional corporate culture isn’t unique to law firms. Jeffrey Pfeffer, a professor at Stanford Business School and author of the book Dying for a Paycheck, said when he held a position on the Committee for Faculty and Staff Human Resources, he was struck by the fact that Stanford’s wellness program focused on exercise and eating better when all of the behaviors that caused people to be unhealthy—overdrinking, overeating, drugs—were caused by their work environment. “The corporate workplace has become increasingly inhumane,” he said. “No one gives a shit about people. Forty, fifty, sixty years ago, organizations used to be communities. They’re not anymore. That ended in the eighties, with the takeover movement, the financialization of everything. We live in a much more transactional world.”

The memorial service finishes and people say their goodbyes. A group of lawyers that worked with Peter over the years head to a bar across the street to reminisce about and glorify a man they didn’t really know. Peter’s siblings head to their deceased brother’s house to spend the night. Evan is staying there, too, so he can drive his uncle to the airport in the morning.

About midnight my phone rings. It’s Evan, and I can tell from his voice he is frightened. Unable to sleep, he went downstairs to poke through some of Peter’s things in the mudroom. He is trying to figure out who his dad was.

“The corporate workplace has become increasingly inhumane,” he said. “No one gives a shit about people.”

Evan saw an earthenware vase Peter has had forever and in which he stored old pens, business cards, paper clips, and other odds and ends. It was sitting in a shoebox with some other junk, tucked behind boots, shoes, badminton rackets, and a deflated football. Evan emptied it onto the floor to look more closely at what was inside. He saw a thin piece of gold foil that appeared to have been ripped from the liner of a cigarette box, folded carefully, about the size of a pat of butter. He unfolded it. Inside were what looked like quartz pebbles. “Mom,” Evan says in a whisper, “I’m pretty sure it’s crystal meth. I took a photo of it and searched online and that is what came up. It looks just like the pictures. I’m kind of scared. What should I do? What if it’s on my hands now? Can something happen to you if it gets on your skin?”

Crystal meth is the common name for crystal methamphetamine, which is usually smoked in a small glass pipe, but it can also be snorted, swallowed, or injected.

I tell Evan not to worry. “I think you just don’t want it near your mouth or nose,” I say, although I have no idea if that’s true, because at that moment I still don’t know anything about the drug. I don’t know if you smoke, snort, or shoot meth—maybe you do all three. Maybe you can eat it too. “Just wrap it back up and put it in the vase and wash your hands really well. I’ll be up there tomorrow and I’ll take it and get rid of it,” I tell him.

“I wish I hadn’t stayed here tonight,” he says, his voice weak. “It’s really creepy. I just don’t want to be here.” I ask if he wants to come home right now. I tell him he can come back tonight, and I will get his uncle a cab to the airport tomorrow morning or go up there myself and drive him. But Evan feels he should stay until the morning and say a proper goodbye.

I hang up the phone but there is no sleep for me. I hadn’t known Peter was using methamphetamine too. I Google it and stare at endless photos of methamphetamine addicts, recognizing in those agonized faces some of what I saw in Peter—the jaundiced look of his eyes, the yellow-brown stains on his teeth, his accelerating hair loss, the sores on his hands and the side of his face.

Long after the memorial service I speak to David Epstein—a scientist at the National Institute on Drug Abuse who heads its assessment, prediction, and treatment unit—about Peter’s descent into addiction, confounding because outwardly at least, he had a good life and still it did not bring him what he needed.

“You mentioned that Peter told you he couldn’t see himself going on like this for the next twenty years,” Epstein says over the phone from his office in Washington, D.C. “I think addiction is primarily something that happens to people that look at the landscape of alternatives available to them in the present and the future, what will be available to them in any foreseeable amount of time, and if none of it looks good,” he says. “They run out of reasons not to try drugs.”

__________________________________

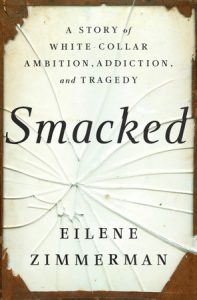

Excerpted from Smacked: A Story of White-Collar Ambition, Addiction, and Tragedy. Copyright © 2020 by Eilene Zimmerman. Published by Random House, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Eilene Zimmerman

Eilene Zimmerman, the author of Smacked, has been a journalist for three decades, covering business, technology, and social issues for a wide array of national magazines and newspapers. She was a columnist for The New York Times Sunday Business section for six years, and since 2004 has been a regular contributor to the newspaper. In 2017, Zimmerman also began pursuing a master’s degree in social work. She lives in New York City.