A blur. Not just one of those things you say, but really, truly, a blur. My eyes cannot focus on the plate of food Adam pushes towards me, I cannot remember getting dressed but somehow I am. My child tugs me down to the floor to play with her trains and there is some peace in that—clicking the little wooden tracks together, slotting them in place, making sure they bend and turn back towards each other, making a circle. Magnetic trains one after another, tiny hands at my aid.

My phone rings and I am back, back to that gnawing at my chest, back to the dropping of my heart. I pick it up, yet another person urging me to confirm what I can barely look at. I am outside now, sitting on the steps of our LA house looking out onto the front yard. The artichokes, their jagged edges, the green, my mind drifting to harvesting them for dinner, but I suddenly can’t remember how to cook them. Back to the voice at the end of the line, they are crying and it makes my tears dry instantly. I listen to them objectively, thinking how sad they sound, how distraught. I enjoy it. I am horrified that I enjoy it. That I like hearing this. Later I will reflect, realise that it was enjoyable to hear someone else in the throes of grief, confirming the worst. It was life-affirming to me, but at that moment I cannot clearly see this so I vacillate between the joy at their racked sobs and disgust at myself that I can bathe so deeply in someone else’s misery.

I find this so addictive that at the end of this call I find myself making another one, and another. I enjoy breaking the news to people, I enjoy hearing their pause, their contention with whether this is fact or fiction, I enjoy being told “I am so sorry, Eirinie.” I want them to be sorry, I want them to pity me because I pity me and I know no other way to be right now.

The sun is setting and Adam comes to tell me there is food inside, if I like. He reassures me he will do our child’s bedtime routine; he wants me to know I can have all the time in the world. Do I want to run, he asks? A walk maybe? I cannot even muster the strength to tell him how tired I am, how I couldn’t run even if I wanted to and I do want to, I want to run far and long until my chest aches from something other than sadness, until my legs no longer move from something other than a paralyzing sorrow, until my head is clear and all I can hear is my own breath, in and out, in and out. But I don’t. I push past him, back inside. I can’t remember if I have answered him but as I fall back into bed I think, let this be my answer.

I sleep for an hour and when I awake the toddler is asleep.

Adam is timid in his question and he seems to be unable to stop himself from asking, “Are you all right?”

“Can I have some wine?” I say, and he is up and pouring a glass immediately, grateful to help.

He knew her too, I think to myself. He knew her well. She was there when we met at the Standard on Sunset, he watched her exhale her cigarette smoke by the pool, her eyes watching us together as if already viewing the future we could not yet see. Mystical. He knew her when he would come to visit me in the UK, stay for three weeks in our small North London apartment, buy us cocktails when we went out, buy us takeout when we stayed in. He knew her. They had gone on walks to the pub alone together, they had discussed music and bands and rock and roll together. He had been the jury to her in-home fashion shows, told her which dress looked best so that she inevitably picked the other dress he hadn’t mentioned. He had been blessed with a nickname, “A.” Simple, yes, but an honour from Larissa. A badge of inclusion, a sign that he was down. He knew her too.

And yet I can’t think of his pain and loss, there is no fucking space in this house for both of our tears. There is no space. Despite my relishing other people’s sorrow down a phone line I refuse to let Adam cry, I cannot bear witness to that. My grief lives here now and there is no fucking room.

I drink a lot that night. I play her voice notes and I cry, too loudly for someone with a young baby in the house. I call her phone even though I know it is in police custody. Somewhere within me, somehow, there is a part that defies logic. I steel myself to hear her voice on the other end, and every time I do not, I am surprised.

You know that burning feeling in your eyes when you have been crying too long? That trite little phrase “I am all cried out”? How true those words ring at three in the morning when I am drunk and forlorn and devastated but unable to muster one single emotion. Adam takes me into bed, I assume, I don’t remember how but suddenly that’s where I am. Adam’s care of me barely registers. It will only be much later that I will mull it over and think of all the little things he did to keep me alive.

Fragmented sentences to Adam. I am writing a history book with my words; I am relegating her to the past tense. I get out half a tale about her before I stop, I cannot finish it. I cannot finish the story because to finish it would be to set it in stone, to cement her as a relic and a character instead of the flesh-and-blood person I want to keep believing she is.

__________________________________

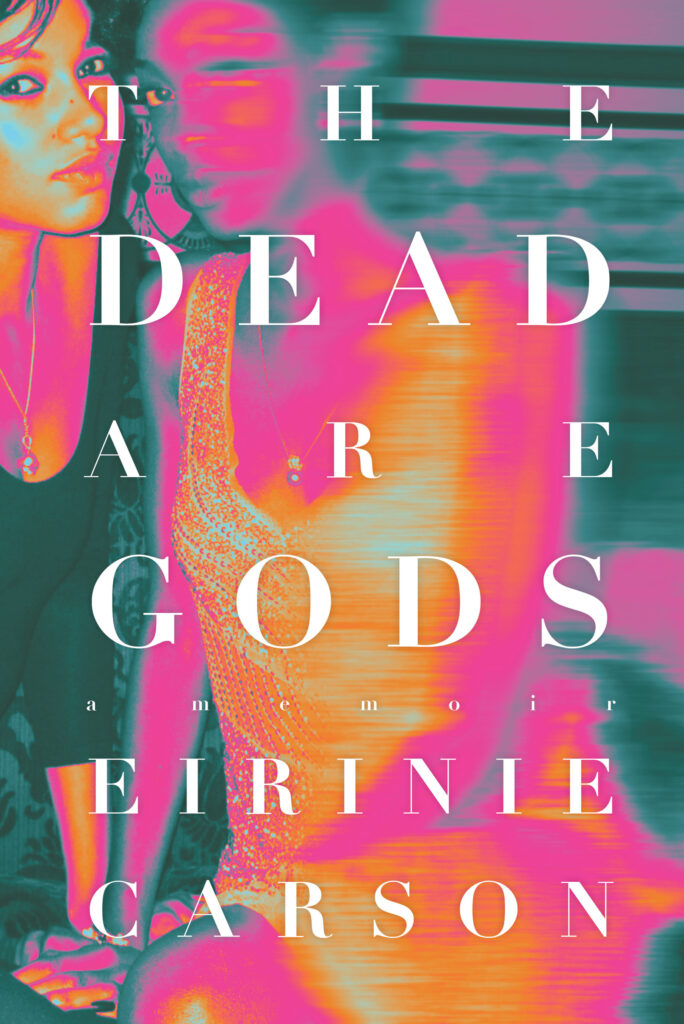

Excerpted from The Dead are Gods, by Eirinie Carson; published by Melville House, 2023.