Now through May 31, you can support Street Books as part of their Spring Campaign. Street Books is Portland’s bicycle-powered mobile library, serving people who live outside since 2011. Their street librarians deliver books, reading glasses, and other important supplies to library patrons, as well as engage in conversations about books and life; their vital work on the streets of Portland create authentic relationships through a shared love of books and building a community of care. You can read a letter from Street Books board member Karen Russell here.

The Big Sky

(Laura)

The seed of the street library was probably planted before Portland, when I lived in Provo, Utah and worked at the Food & Shelter Coalition. My job was to arrange emergency housing and set up volunteers to serve meals, but I also soaked in the stories of the people who came through. It’s where I met Urban Robbin and TJ Reynolds, both in their late 70s. There they were, crafting their days from nothing, with no particular place to go. Urban was squatting in a concrete basement and rode a kid’s bicycle with a banana seat. TJ crushed up iced animal cookies in his chili and sang “Down by the Old Mill Stream.” I looked forward to their stories each day because they felt like the most authentic characters I knew. My longing for people living real, sometimes roughshod lives, may have had to do with the artificiality of the rest of my day. At the time, I was attending a religious university, where a sea of shiny people with very good attitudes marched to and from their classes on campus. It was the early 90s.

Fast forward to 1999, when I lived with my boyfriend, Ben, and one each of our younger brothers in a house in inner Southeast Portland. I volunteered at the community radio station, KBOO, where I learned how to produce features and mix programs on the boards. I anchored the news every Wednesday night and once, on a broadcast, pronounced the Irish political party Sinn Féin, just like it looks: “Sin Fine,” instead of “Shin Feign.” It was bad. I repeated it several times and my co-anchor winced each time. But they couldn’t fire me because I was a volunteer. On my way to and from the radio station, I’d pass through the courtyard of St. Francis of Assisi Parish and greet the folks who gathered outside with their bedrolls and dogs and shopping carts, tarps, and heavy boots. I decided to see if anyone would be game to have a conversation with me, so I could create a radio feature composed of their stories for KBOO’s annual “Homelessness Marathon.” That’s how I met Quiet Joe. As I stood peering into the dining hall, trying to get my nerve up to approach the guys, he said, “You’re welcome to go in if you need a bite to eat.”

Joe told me that he’d lived outside by choice for 14 years, was originally from the East, and preferred to live outdoors and not have to pay someone else for a roof or utilities or that sort of thing. He found scrap metal and wire to recycle, and he made an okay living at this. We talked about books we liked, and discovered that we had a favorite author in common, the western writer A. B. Guthrie Jr. Later, I reflected on our conversation and realized that it was surprise I’d experienced at learning we’d both liked Guthrie’s novel The Big Sky the best. This bothered me. What had I assumed about Quiet Joe before we’d had a conversation? Some weeks later, I found a few Guthrie titles at a used bookstore, tucked them into a brown paper bag, and passed them to Joe the next time I saw him.

*

Équipage Pathétique

(Ben)

I had been outdoors for about nine months by then, and still hadn’t recovered from the nasty shock of falling into the bottom of the barrel and then seeping on down through the cracks. I slept in Old Town, with a few spare clothes and a couple of blankets. Most nights, the sidewalks from the bridge and around Second Avenue to Couch were haphazardly strewn with various specimens of humanity, some of whom a chagrined creator might have called failed experiments. I was usually the third or fourth experiment down from the Mission.

I showed him my rudimentary sketches: a bicycle with a square box full of books attached. What if it could be a library on the street? What if it focused on people outside?To a new guy, just finding a spot was a source of anxiety. I soon enough worked out a simple four-step routine. Breakfast at the Mission, 7:00 am. Kill time. Dinner at the Mission, 6:00 pm. Find a spot on the sidewalk. This was challenging. Wasn’t two weeks before I was on Burnside over the MAX tracks, when Andre Payton came to a bad end. Corner of Second and Couch. They counted dozens of bullets. Welcome to Old Town.

There were a few doorways on Third between Couch and Davis, good rain spots, availability various. I commandeered one of them and it turned into “my” spot, even though there is really no such thing as a reserved spot. Think this one over: If you have to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, you can go to one of the nearby johns, and when you get back, maybe some of your stuff is missing. Or you can take everything with you, and when you get back, maybe someone is in your spot. Or you can just give up and let fly whenever and wherever you have to. What I had taken to doing was not drinking anything past about noon. Not the healthiest approach, but it does show initiative, and employers take that into consideration.

Gotta hand it to the cops, it was fairly slick how they did it. Showed up about 4:00 am and started rousting people, one at a time, handing out exclusions, so you don’t even know they’re there until it’s your turn. You see, under the bridge is considered part of Waterfront Park. Park closes at midnight. So now I couldn’t be in the park, any part of it, day or night, for six months. Bummer.

Didn’t know where I was going to sleep, so I went back to the sidewalks around the Mission and the overflow under the bridge at the Skidmore MAX stop near the Mission. Under the bridge there were some aggressive types, usually the drinkers, that got belligerent, and it was a creepy place in general. That night there was a confrontation I overheard that sounded like someone had pulled a knife, because I heard a girl say, “Do it. You don’t have the balls.” Then I heard the sound of someone falling down. I heard these things. But I did not lift my head to see what was happening.

*

Building the Library

(Laura)

I was spread pretty thin already, but I’d begun to experiment with socially engaged art projects, work that ventured out of the traditional spaces of studio or gallery and into the streets. My interest in these sorts of projects dated all the way back to my early days in Portland, when Ben and I had launched his brainchild, Gumball Poetry, a poetry journal published into gumball machines that lived in bookstores and cafés in Portland and other cities. More recently, with the help of my brother James, I’d created a giant rolling mobile gallery for Portland State University. It displayed objects collected from PSU students in tiny plexiglass windows: socks with text that read YOU CAN’T AFFORD ME, a crucifix, a ceramic dinosaur mug that changed color when filled with hot liquid. On either side of the Object Mobile, a platform opened to display an old Royal typewriter. I set chairs out so that passersby could sit down and type about the objects in their lives that were precious to them.

I liked the idea of creating an intersection where these conversations could happen. Since I’d already demonstrated an affinity for beautiful, ungainly, rolling creations, I roped my brother into yet another project (in post-recession Portland, he was one of many unemployed architects looking for work). I showed him my rudimentary sketches: a bicycle with a square box full of books attached. What if it could be a library on the street? What if it focused on people outside, instead of those who had easy access to an indoor library already? I knew from personal experience that there was nothing so powerful as a book to transport you from reality, to escape a particular circumstance for an afternoon. James was in. We would build a library and it would roll up into the squares, the fountains, the sidewalks of Portland, and it would serve a group of people who rarely got invited to anything, given their status as outsiders.

“You’ll never see the books again.”

That was a sentiment I heard more than once when I described the project to people, but I couldn’t shake the idea of a street-level library.

Would I see the books again? There was only one way to find out.

*

GQ

(Ben)

At first, she looked like any other street librarian, complete with the cards in the books and Post-it Notes and paper-clips. Bicycle parked, and little shelf pulled out, displaying the collection. I graciously overlooked the complete lack of any Wodehouse titles on her shelves, but did mention in passing that a well-maintained library does require some attention. Only too late would I learn that here was a teacher turned recalcitrant schoolchild that refuses to do her assigned reading. But I didn’t know that yet.

I’d arrived in my ratty-looking coat. Scruffy beard. Hair going every which way, like I’d just stepped off the cover of Gentlemen’s Quarterly and then into a threshing machine. The way I must have looked to Laura at the street library, it could easily have been straight out of Wodehouse. Describing one of Bertie’s lovesick acquaintances, he writes, “He looked like a character in one of those Russian novels, trying to decide whether to murder several relatives before hanging himself in the barn.”

*

Surprise!

(Laura)

After a particularly wet and dispiriting spring (very few people wanted to stand outdoors talking about their favorite novel—everybody who could find shelter had done so), I received a phone call from a woman at the National Book Foundation. Street Books had won a prize! This meant $2,500 and a trip to New York, where I would be invited to speak at the Ford Foundation. In Portland, we’d had articles written about us in the Oregonian, the Portland Mercury, and the Portland Tribune. Suddenly, it felt like the little street library was starting to take off.

*

Unlikely Checkouts

(Ben)

In the fifth year of Street Books, I started showing up at the shifts as a second pair of hands and mostly because it was my best chance to see my friends. I think that was the last year of the solo shifts, once we all saw how much easier it was with a sidekick. I would find either Diana or Laura at R2D2, or the Worker Center, or St. Francis. One day, I brought Nineteenth Century Russia with me, knowing that it would be a tough sell, which it was. After a few more visits, it was Diana who finally checked it out.

I tried to bring something for every taste. I knew that Peter Lovesey’s Wobble to Death had only the tiniest market niche out there. It was a murder mystery that took place at a wobbling event. The sport of wobbling, an indoor track-walking marathon where the last walker standing takes all. Turn of the century England. The first checkout was easy; I forced it on someone. Took it back the next time I saw them, and later that same day came across a guy who was a huge fan of the BBC and wanted to read the thing. You just never know.

The way I must have looked to Laura at the street library, it could easily have been straight out of Wodehouse.I kind of made it my shtick or whatever to try and promote the hard-to-place books. Cherie Calbom’s Juicing for Life, for example, while a fascinating book in its own way, is a real tough sell to people who do not have a juicer. But someone did eventually check it out. The Arms of Krupp by William Manchester also has a limited appeal, but as I was pitching it to the guy on my left, the guy on my right said, “Hey, let me see that.” Turned out he knew a lot about the Krupps and their centuries-old armament business.

The John Dewey book, on the other hand, was always going to be a struggle. The Child and the Curriculum, as you can see, is targeting a very exclusive readership. “One of our more overlooked thinkers,” is how I began my pitch. And we did check it out, but it doesn’t count. It was a couple, and he wanted to leave, but she wanted him to get a book, so he asked if we had any nonfiction and I said, well there’s this, and without even looking at it, he took it. No count. He even returned it later, but I don’t think he read it. I know I wouldn’t have.

And the self-help books. I read a few of them in my day. I suppose I got a couple of fresh ideas from them. I suppose the ones they got now do about the same thing, if you find the right one, which we did. It was by Francesco Marciuliano, called You Need More Sleep: Advice from Cats. A picture of a cat on the cover, looking pleased.

*

HQ

(Laura)

The bulk of the administrative work for Street Books had always taken place on our respective kitchen tables, but I knew that somewhere in the city was a place for our organization to live, an office where we could settle in and trade our services for rent. I got a lot of faint smiles and pats during this time—given the real estate boom in Portland, it was hard to imagine we’d find a low-cost space for our headquarters.

An architect friend told me about the new affordable housing project she was working on and added, “I sure wish we could get Street Books in there.” She put me in contact with a Person in Charge, whom I commenced emailing periodically over the next year. The complex would be located next to St. Francis, replacing the park and courtyard. By then, we had been holding library shifts for a few years outside the dining hall.

In the tradition of naming a place for what it previously contained (Quail Run, Hawk’s View), the complex was called St. Francis Park Apartments. Eventually, miraculously, all the emailing paid off, and we were able to negotiate an agreement with the sponsoring agency, Catholic Charities, to take over a small room in exchange for operating an on-site library for the residents of the building. While the space may have been intended for storage—being mostly concrete with one wall of Sheetrock—it did have electricity, and once we filled it with a few desks, a couch, chairs, and two rugs (not to mention a thousand or so books), it was quite homey. It’s hard to overstate what this meant to a small, scrappy street library, to have a place to store administrative stuff, library supplies, Armando the taxidermied armadillo, and a string of bike-shaped lights adorning one wall of bookshelves.

We moved in on a chilly afternoon in November 2017. The following month we held a cookie and cocoa party to spread the word about the new on-site library. Rain had typically closed down our operations on the book bike for a few months in winter, but suddenly we could stay open all year. Since a number of the folks at St. Francis were coming from lived experience on the streets, we would now be able to connect with library patrons indoors. Julie Keefe—who in 2012 had been named Portland’s first Creative Laureate—set up a photo booth in one corner and people showed up in Christmas sweaters, wanting to have their portraits taken. It was not lost on me that we’d taken up residence a block from where I’d lived eighteen years earlier, at the corner of SE 12th and Oak. This was where I’d spoken with Quiet Joe about A. B. Guthrie Jr. It felt like coming home.

_______________________________________

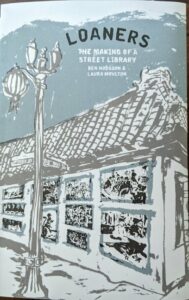

This excerpt was adapted from Loaners: The Making of a Street Library by Ben Hodgson and Laura Moulton. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Perfect Day Books. Copyright © 2021 by Ben Hodgson and Laura Moulton.