The Complicated—Yet Inspiring!—History of Spiritualism in America

S.E. Porter on the 19th-Century Movement and Its Righteous Yet Flawed Fight For Justice

Here’s a true story; you might have heard it before, or one very much like it.

1873. A medium named Florence Cook became famous for “materialization” séances. With the medium supposedly unconscious in a closed cabinet, a willowy female figure claiming to be the long-dead spirit Katie King walked through the séance room, beguiling such observers as the scientist William Crookes, who discovered the element thallium. In December a suspicious visitor, Mr. Volckman, grabbed hold of the spirit, and revealed her to be the medium.

In novels, in movies, in our collective dreamscapes, the con-artist medium appears as again and again: cracking her toes to simulate spirit rapping, maybe, or coating her own skin in phosphorescent paint to create a luminous spirit hand drifting over the company. The medium in these stories is female, wily, sociopathic, hysterical at best; the characters who unmask her are calm, heroic males, stripping her of her mystical veils with their powers of rationality.

It bears repeating: these stories—at least regarding the tricks practiced by con-artist mediums—are true. Characters like Florence Cook appeared again and again from the beginning of Spiritualism in 1848 through its lingering decline in the twentieth century. The numbers of outright fraudsters increased sharply after the Civil War, and again after World War I, preying on the bereft families of dead and missing soldiers. Then as now, scammers were endemic to capitalism, and calling up the dead was the scam of the day.

*

1853. A twenty-five-year-old ex-teacher, Achsa Sprague, had been bedridden with a joint disease for five years. She’d tried every treatment she could, and found them all useless. Then she experienced a rapid recovery and attributed her healing to the spirits. What the spirits asked in exchange was the unthinkable: that she go forth and speak in public—an act forbidden to women, according to the dictates of her time, by the Apostle Paul.

In following the directions of her spirits, Achsa joined other Spiritualist trance speakers, some of them girls as young as twelve or thirteen, in ascending stages across the country to preach a new Spiritualist doctrine, not only of communication with the dead, but of absolute human equality. Achsa’s surviving diaries prove her passionate sincerity. Whatever inspired her and her fellow trance speakers, many contemporaries marveled at the eloquence of these girls and women who were often working-class and poorly educated. They toured the country. They generally spoke with no preparation, since they were informed of the subjects for their talks only moments before they began. How could these ignorant country girls understand so much, people wondered, unless the spirits spoke through them?

The Spiritualists fought for justice, and now we owe justice to them: the justice of remembering that they were some of the noblest and bravest people of their day, as well as some of the worst.

A floating hand or a levitating table is easy enough for a clever conjurer to fake. But who can fake the courage, conviction, and ardor that would lead a young Victorian woman or child to stand alone in front of a skeptical crowd, and present what was—in modern terms—a radically intersectional vision of liberated humanity?

Until I began researching the history of Spiritualism for my novel Projections, all I knew about the movement were variations on the con-artist duping grieving parents in the darkness of the séance room. I didn’t question whether there were other stories just as true. Internalized misogyny made it easy to accept a version of history where women are either deceitful—we all know women are deceitful—or irrational suckers, so undone by grief that they’d fall for anything—we all know women are irrational.

My expanding knowledge of what was once a major American religion, largely led by women, came as a revelation. The Spiritualists were fervent abolitionists. Their feminism went well beyond what the suffragists of their day proposed. Rather than simply demanding the vote, many Spiritualists demanded the right to voluntary motherhood—a right that eludes us almost two centuries later. There were Spiritualist women who refused to take their husbands’ names in marriage, or sometimes to marry at all. Their split with the suffragists after the Civil War came about because the Spiritualists were uncomfortably extreme, even embarrassing, with their insistence on true equality.

The trance speakers exemplified the passion of the movement. Some of the trance speakers might not have acknowledged their own beliefs in radical equality, even to themselves, without the permission their new inspiration granted them: to feel, to know, to raise their voices. And without the borrowed authority of the spirits who allegedly spoke through them, who would have listened? What old men in their frock coats would have thought that the views of teenaged girls deserved their consideration?

*

1850. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, a savage measure that allowed federal agents to kidnap fugitives after they reached the northern states and return them to face brutality and sometimes murder from vindictive owners. It also imposed a six-month sentence for harboring fugitives. Isaac and Amy Post—committed Spiritualists as well as abolitionists—continued to run their station on the Underground Railroad, hosting as many as a dozen fugitives a night.

Isaac Post had become a medium, channeling spirits through automatic writing. And the spirits told them it was the right thing to do.

According to general Spiritualist doctrine, the individual conscience was absolute. Any authority claimed by any human being over another was blasphemous. Each person was a conduit for the divine, answerable only to the truth that manifested within them.

That belief explains why so many Spiritualists, like the Posts, were fiercely opposed to slavery. It doesn’t explain what gave them the courage to act on their convictions. Fear so often stifles our best selves and our greatest potential. But what if we distance ourselves from our inner voice by calling it a voice from the beyond? Suddenly its call to courage is holy.

Suddenly answering that call becomes both possible and necessary.

*

1882. The medium Katie Fox received an invitation to Russia. Her commission was an odd one: to use her communion with the spirits to guard Czar Alexander III from assassination during his coronation. The spirits took advantage of the visit to lecture the Czar on reform and warn him against repression.

Katie Fox, along with her sister Maggie, launched the Spiritualist movement in 1848 when the two teenage girls claimed the ghost of a murdered peddler was communicating with them via raps. Forty years after they began Spiritualism, they turned around and denounced it and declared their long careers entirely fraudulent. Then a year after that they recanted their confessions. One intriguing point is that Maggie Fox was moved to attack Spiritualism by her failure to contact the ghost of her dead fiancé. The fact that she tried—and was embittered by the attempt—doesn’t exactly suggest unmixed cynicism. If she didn’t believe in the spirits, why did she hope to talk to one? The case against the Fox sisters is strong enough, though, that it’s tempting to say that, for Spiritualism, the end was present from the beginning. The movement started with a fraudulent prank, and later fell through its decline into widespread corruption.

Still: Katie Fox, former obscure country girl, probable fraudster, rode her spirits all the way to an audience with the Czar, and used that unlikely opportunity to try to change the world. This isn’t the only story of its kind about her. In a session with an industrial magnate who’d made his fortune from matches, she channeled the spirit of a match-boy—one of the child laborers who’d earned her client his money. The child-ghost upbraided his former employer for the cruelty of his working conditions.

(It’s worth noting that the stories of anomalous events around Katie Fox are weird enough that her biographer, Barbara Weisberg, was left with some doubt as to whether the youngest Fox sister could have manifested genuine psychic powers, at least occasionally.)

(Also weird: a skeleton the right age to belong to the murdered peddler—if he ever existed—was found much later, buried in the basement of the Foxes’ farmhouse.)

1857. Andrew Jackson Davis—sometimes described as the John the Baptist of the Spiritualist movement—discussed proper seating at a séance. Some seating arrangements called for men on one side of the table, women on the other. Others said that men and women should alternate, “as so many zinc and copper plates in the construction of magnetic batteries.” But here’s where things get interesting: assigned sex didn’t determine who was a man, and who was a woman. Instead the question of gender was decided by “attributes of character” and “intellectual temperament.”

Fucking 1857, and the Spiritualists were affirming trans identities. The movement disdained hierarchies and official doctrines, but Andrew Jackson Davis was about as authoritative as a Spiritualist could get.

Spiritualist thinking tended to be dualistic and heavy on binaries. To a modern sensibility, some of those dualities are downright obnoxious; women were understood as “negative” and men as “positive” for example. It would be difficult to map our understanding of nonbinary genders on their worldview.

It’s easy, though, to see how Spiritualism embraced gender-fluidity and trans-genders, even if they discussed their understanding of gender in very different terms from ours. Mediums assigned female spoke with the voices of men; mediums assigned male spoke as women. The medium Jesse Shepard would enter trances and sing in a beautiful soprano voice that he (or she) credited to the female spirits flowing through his (or her) throat; critics were quite clear that it was not falsetto. The dubious Madame Blavatsky—in her Spiritualist days, before she founded Theosophy—was known to sign letters “Jack.” Dress reform was among the favored Spiritualist causes, and there were Spiritualists assigned female who wore men’s clothes.

Again the spirits—or a belief in the spirits—freed people to live out their inner truth.

*

1922. Mrs. Tompson, smarting after her rejection by the Scientific American committee then searching for a genuine medium, sought out easier marks by performing at the Church of Spiritual Illumination. A materialized spirit appeared in front of the cabinet where the medium sat entranced, and one of the Spiritualists in the audience approached the apparition. Mr. Tompson seized the seeker’s arms to prevent his touching the glowing figure.

So the man took a bite out of the ghost.

His mouth came away, gauze caught between his teeth.

Not all Spiritualists were such suckers.

One striking aspect of Spiritualist thinking: how many of them understood what they were doing as a scientific enterprise. Instead of demanding faith, they insisted their beliefs were subject to empirical investigation. Very few religions have the nerve to dismiss faith and invite scientists to dig in. The fact that the Spiritualists did exactly that testifies to their sincerity, even as it contributed to the collapse of their movement.

The history of Spiritualism is thick with prominent scientists. Some were dupes like William Crookes, hopelessly infatuated with a girl who called herself a ghost. Sir Oliver Lodge, who did important early work on radio and X-rays, was so convinced that he was communicating with his dead son Raymond that he wrote a book about it. Nobel laureate Charles Richet did experiments on ectoplasm, that mysterious substance supposedly oozing from the spirit world. It’s a fact I find baffling, since a scientist would presumably notice if his “ectoplasm” was shredded cotton. What on earth was Richet examining?

Alexander Graham Bell was motivated to invent the telephone partly by the hope of speaking with his dead brother. His assistant Thomas Watson—the man who decided that telephones would ring—was a serious medium who held regular séances and thought the telephone would make contact with the dead easier. (Some squeamish modern writers say Watson “dabbled” with Spiritualism. Daily séances are not dabbling.) Thomas Edison attempted to make a ghost-phone, too. “I can make an apparatus better than Ouija for talking with the dead—if they want to talk.” Edison was not a Spiritualist, but he did hope to find a way to strip (largely female) mediums of their power. If anyone could dial-a-ghost at will, mediums would be obsolete.

Now I’d like to address the ugliest charge against Spiritualism: that vicious mediums defrauded bereaved parents by impersonating their dead children.

As with all the other crimes alleged against Spiritualist practice, this charge is true.

And once again, there’s more to the story than the stories we know.

When Spiritualism arose in the middle of the 19th century, child mortality was around fifty percent. The drumbeat of grief never ceased. And when Spiritualism arose, Calvinism was still the dominant strain of American Christianity. Calvinism, which held that a large majority of humankind was damned from birth, predestined for hell, informed those grieving parents that their lost babies and children were most likely cast on the infernal fires. Forever.

“Violence is the performance of waste,” wrote the scholar Joseph Roach, and that’s true as well of the imaginative violence performed by those Calvinist ministers. For them to tell a parent that their child was damned was to say, By the power vested in me by the Almighty, your love is waste, your heart is waste. So are your tears. And for the mother, there was an additional message: The labor of your body—in carrying that child, giving birth, breastfeeding, watching through the nights—is trash for the fires of hell. All you did is worth less than nothing. All you accomplished is the eternal misery of your darling child.

If we can allow them justice in our collective imagination, they’ll give us something in return: an understanding of what it means to accept inspiration.

Then the Spiritualists came in, and insisted that all those dead children were just fine. They were still close by, and they were even growing up. The parents’ love, so far from being wasted, remained with their children in the Summerland, as the Spiritualists called their afterlife. A religion led by women rose and radically revalued the work of having and raising children. It revalued the children themselves.

*

2016 or so. Morbid Anatomy, a delightful Brooklyn institution, hosted an evening with two mediums. They were visiting from Lily Dale, a remnant Spiritualist community in upstate New York. I went to see them. Like a good Victorian, I went with a receptive mind, half-hoping to witness things I couldn’t explain.

Both of the speakers were rather blowsy, fiftyish women. One announced that she would draw a portrait of a ghost present in the room. She assured us that someone in the audience of a hundred or so people would recognize the spirit.

After a few minutes’ rapid sketching, she held up a face that, except for being elongated and almond-eyed, was fairly generic. She waited hopefully for one of us to claim the ghost. When no one did, she seemed genuinely confused, even hurt. I thought she was used to playing to a more cooperative crowd, one that would join her in the creation of a collective fiction. I never got the impression, though, that she was deliberately lying.

The other medium said she was picking up on another spirit: somebody’s mom. The spirit was wistful, a little sad. Whose mom could it be?

Like the portrait, the ghost-mother found no takers. She lingered like an unwanted puppy at the pound.

There was no deceit in the presentation, no theatrical trickery. It would have been a more amusing evening if there had been.

A number of historians trace the decline of Spiritualism to the escalating demands placed on mediums after the Civil War. In particular, the craze for “materialization” séances—in which a spirit was supposedly conjured, in whole or part, in bodily form—led mediums to cheat. Fraud was so prevalent by the late nineteenth century that some of the Spiritualists themselves were mourning their degeneration. They had traded their activism for spectacle. The medium Melvina Townsend, for one, spoke longingly of “days gone by, when angel Achsa Sprague stood as a queen of power.” As I explored the history of Spiritualism, the fall of this bright, brave, idealistic movement into tawdry deceit struck me as utterly tragic. Even worse, a movement that began by campaigning for women’s equality wound up playing into some of the nastiest misogynist stereotypes.

The Spiritualists were a pack of frauds and dupes, of self-deluded hippies and crackpots.

The Spiritualists were absolute heroes who fought for racial and gender equality, for self-determination, and for the primacy of the individual conscience. Their efforts to change the world presaged our modern struggles for justice. They were magnificent in their fierce rebellion against a repressive society.

Both of these stories are true.

But because of our society’s relentless misogyny, we remember only one of them.

*

1904. The painter Hilma af Klint, a member of a Spiritualist circle consisting of five close friends, received a message from her spirit guide Ananda. Would any of the five friends accept a commission to reveal the spirit world through painting? The other four members of the circle fearfully refused the invitation—to paint in the way the spirits asked might cause madness.

Hilma af Klint accepted the challenge despite her friends’ warnings. Then, under the guidance of another spirit, Amaliel, she invented abstract painting a decade ahead of Kandinsky.

Hilma af Klint offers another instance where belief in the spirits led to extraordinary courage—in her case, the courage to live as a creative visionary. To make something wonderfully new. Unlike ectoplasm, her incredible paintings are unquestionably real.

I tend to think that the Spiritualists took an emotional truth—that our dead are always with us—and literalized it with a rather heavy hand.

They also took an artistic truth—that our creative powers seem to flow from something much larger and wilder than ourselves—and called that inspirational wellspring the spirit world.

Like the trance speakers, like Isaac and Amy Post, Hilma af Klint was unquestionably inspired. Her glorious paintings never would have come into being so far ahead of her time if she hadn’t believed in a voice that stood outside herself.

I would never call myself psychic, but in that sense—in the sense of letting go, and accepting inspiration—I think I understand a bit of what it means to be a medium. Writing a character in first person can feel like channeling another personality. Someone speaks through me in a voice complex, imperious, and not under my control. It’s easy for me to imagine how a similar experience could persuade someone they were truly a conduit for the dead.

The Spiritualists fought for justice, and now we owe justice to them: the justice of remembering that they were some of the noblest and bravest people of their day, as well as some of the worst.

And if we can allow them justice in our collective imagination, they’ll give us something in return: an understanding of what it means to accept inspiration. They’ll show us what we can accomplish if we listen to the spirits telling us to be bold and defiant and visionary—even if we accept that those spirits are our own.

*

Some of the books that inspired and informed this essay include Radical Spirits by Ann Braude, Talking to the Dead by Barbara Weisberg, Ghosts of Futures Past by Molly McGarry, and The Witch of Lime Street by David Jaher. I recommend all of them to curious readers. I’m also indebted to Fits, Trances, and Visions by Ann Taves, The Telephone Book by Avital Ronell, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future by Tracey Bashkoff, The Shadow World by Hamlin Garland, and assorted internet sources on spirit writing and photography, especially articles in The Public Domain Review.

__________________________________

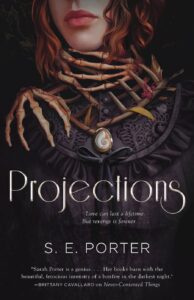

Projections by S. E. Porter is available from Tor Books, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

S. E. Porter

S. E. Porter is a writer and artist. As Sarah Porter, she has published several books for young readers, including Vassa in the Night. Projections is her adult debut. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and daughter.