The Complicated History of the Black Joke, the Ship That Battled the Slave Trade

A.E. Rooks on the Ongoing Repercussions of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The fire made for a beautiful sunset. The screams of sailors and slavers were a memory. The terrible cacophony of the cargo over which they’d struggled had also gone silent. It was as if the flames consumed not just ship timbers but sound; stillness had settled where the breeze of the sea refused to let the smoke rest, despite the crowds of people the blaze had drawn to the harbor. If evidence remained of the lives lived on board the now-empty vessel, it went up with the pungent smell of the burning decks, and the acrid scent of charred wood and whitewash accompanied the crack and snap of sparked beams.

Naturally, the ship had been looted first, everything of value removed. The western coast of Africa was not a place where stores and sails would go to waste; what could not be used would be sold or traded by the same people who’d destroyed one of the finest Baltimore clippers ever to sweep across the open sea.

It wasn’t the first time this notorious ship, the Black Joke, had been laid bare. Only five years previously, it had been a legendary slaver making quick work of a terrible job, with a reputation for being too fast to ever be caught—but one fortuitous night it had been. Repurposed from horrific duty to a higher calling and outgunned for much of its career, Black Joke nonetheless set about capturing slavers in the same waters it had so recently cruised for human chattel—and persevered. In a world where news traveled in months, rather than minutes, the slaver-turned-hunter was famous in both incarnations, renowned in battles, outmaneuvering ships of every nation until its precipitous end. Those bearing witness to that demise knew that this time there would be no next chapter, no last-minute reprieve. This was irrevocable. It was not the sort of conflagration from which one arose.

Toasted by its peers and enemies alike upon its destruction in 1832, it’s possible people wept upon hearing the news of Black Joke’s ignoble end. Certainly the free Black population of Freetown, looking on from afar, would have saved the ship if they could have. The Black Joke had seized thirteen slave ships in its short life as an enforcer of abolition, but by many accounts, the tally in human lives spared bondage, at least in the immediate sense, was much greater. Setting aside the wider impact of the chilling effect and created by Black Joke’s mere presence on the water—which wasn’t insignificant—while the ship was active, approximately a quarter of all the enslaved who arrived at Freetown to be officially liberated arrived care of this single ship and its crew.

The crew on board included everyone from eager teen sailors (as young as thirteen) to grizzled veterans, in a diversity of ethnicities that demonstrated the incredible reach of the still-growing British Empire. A symbol to the whole of the West Africa Squadron (WAS) to which it had briefly belonged, the Black Joke had found and, at least temporarily, freed at least three thousand people. A figure to compare with how many the ex-slaver had itself brought to bondage, to be sure, but overall, barely a drop in the ocean of lives lost to the trade.

The Black Joke had seized thirteen slave ships in its short life as an enforcer of abolition, but by many accounts, the tally in human lives spared bondage, at least in the immediate sense, was much greater.

But how had it come to this? For four years, the Black Joke, itself a captured vessel, manned by a rotating crew, plagued by illness, dogged by bureaucracy and pirates, nonetheless sailed as the scourge of traffickers, releasing thousands of the enslaved from the cramped decks of ships flying flags from dubious diplomatic partners. Its captains and commanders had cracked slaver codes, discovered secret trade routes, and brought home the kind of prize ships that could change a man’s life, and perhaps even his station. It had navigated shoals corporeal and political—whether off the coast of western Africa or ensconced in the Admiralty House in London, both were surpassingly treacherous. As those made rich from the sale of human flesh lifted a glass to a common enemy’s downfall, speculation must’ve raged regarding who or what had destroyed the most celebrated thorn in the Atlantic slave trade’s side.

To answer this question requires a deeper exploration of the transatlantic slave trade than many of us, especially in the United States, ever encountered in school. If your education was anything like mine, what we learned about the slave trade as children and teens—if we learned much of anything at all—can be distilled into two broad statements: it was extremely unpleasant, and it ended before the Civil War. Beyond these limited understandings, many seem to believe that after bans were enacted . . . sometime in the 1800s, slave trading came to a mostly natural end.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Despite its short tenure in the service, the journey of what would eventually become His Majesty’s Brig Black Joke and its crew touched on nearly every aspect of this frequently overlooked chapter in the popular history of the abolition of slavery. If one begins with the ship’s history as a slaver and its unlikely capture, to follow in the Black Joke’s outsize wake is to discover a ready microcosm of a difficult transition period for Britain. From biggest slavery profiteer before the turn of the 19th century to the most vociferous proponent of abolition soon thereafter—all while attempting to drag the rest of the world with it for reasons both high-minded and pragmatic—decades of British interventions in the slave trade, for good and ill, are reflected in Black Joke’s genesis, incredible campaign, and ultimate end.

In the oft-ignored era post-dating Napoléon and predating Victoria, the Black Joke’s crew, fortunes, and failures can be linked to not only the global evolution of the slave trade, but the demise of the Age of Sail, the increasing steam behind the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of Pax Britannica. However, this is not just a story of big ideas and global changes. The daily tensions and privations faced by the crew and their captured prizes—particularly in a time when the West Africa Squadron (also known as the Preventive Squadron) was arguably the most dangerous post in the British Royal Navy— reveal courage and suffering, greed and folly, all against the backdrop of one of the greatest blights on humanity’s collective history. The actions undertaken by these sailors may have occurred on salt-crusted rigging or below enemy decks sluiced with blood, but they had the potential for far-reaching and explosive repercussions on the international diplomatic stage and for the cause of abolition as a whole.

The Black Joke’s voyage in the contemporary imagination went much further than its patrol. As we struggle to dismantle racist and colonialist legacies today, the Black Joke’s journey demonstrates that battles for freedom have never been short, uncomplicated, or without sacrifice—though they are, conversely, easily forgotten. Far from dying a slow, if mostly natural, death, the slave trade had to be actively dismantled over many years of tense maneuvers in storms both political and nautical, and if British sailors had a hand in it, so, too, did Africans, enslaved and free, as well as ardent abolitionists, politicians both reluctant and enthusiastic, and collaborators the world over.

This is not, however, yet another narrative in which Britain mostly saves the day. The history of the Black Joke (and certainly that of the Royal Navy) resists such simplistic assessment. Far from a story of unmitigated White Saviorism, this is a complex history with few uncomplicated heroes, even when writ as small as a single ship in a much-larger landscape. The slave trade, the fits and gasps of its final decades, the aftermath—the choices made then have filtered into every facet of our modern world; the Black Joke’s cruise is still in the food we eat and clothes we wear, it is still in the land we live on or occupy, it is in our wars and our peace and our borders and our economy and how cultures the world over grapple with legacies of colonialism and racialized violence.

The repercussions of the transatlantic slave trade surround us, still. Regardless of which side of the Atlantic we live on, the reverberations of centuries of human trafficking and the turbulent decades encompassing the fight to finally end it are still felt now; it is in reading and writing about escaping the slave trade that one realizes that the legacy of the slave trade and its abolition is yet inescapable.

In our current political climate, one of tense negotiations and tenuous alliances in the face of an increasingly shrill White supremacist movement, perhaps these lessons from an untidy history, gleaned from a battle for justice that was waterlogged and dirty, nuanced and treacherous, can help in navigating society’s way to better shores. Though one ship alone could never hope to stop the proliferation of slavery, to read the history of the Black Joke is to wonder if its example could have, to wonder why its success couldn’t be replicated, to wonder further at the avarice, inefficiency, and moral relativism that frequently scuttled even the best efforts to halt the flow of the enslaved across the Atlantic.

So much more could have been done decades sooner to effectively police the transatlantic slave trade. Hundreds of thousands of lives might have been spared the lash or saved outright had intrigue and ineptitude not created a scenario in which the greatest navy on earth somehow fielded a woefully understaffed fleet to contend against the flood of slavers pouring from so many ports.

Even a ship without peer, when situated in a military bound by distant bureaucracy, on a coast known for deadly maladies, in waters rife with hostility, was poorly equipped to cope with the sheer magnitude of the task set before it. This tiny ship of fifty or so men was Britain’s reflection on troubled water—an image of morality and principle, regularly disrupted by waves of indifference to and profit from the trade in human chattel. As the embers of the Black Joke crumbled near Sierra Leone, one thing was clear: the Royal Navy would never contain its like again.

_________________________________________________________

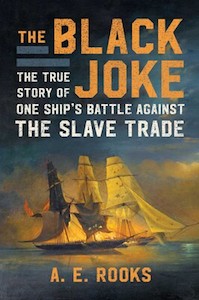

Excerpted from The Black Joke: The True Story of One Ship’s Battle Against the Slave Trade by A.E. Rooks. Excerpted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2022 by A.E. Rooks.

A.E. Rooks

A.E. Rooks hopes to always be a student of history, though that hasn’t stopped her from studying everything else. She is a two-time Jeopardy! champion with completed degrees in theatre, law, and library and information science—and forthcoming degrees in education and human sexuality—whose intellectual passions are united by what the past can teach us about the present, how history shapes our future, and above all, really interesting stories.