The Complicated Afterlives of

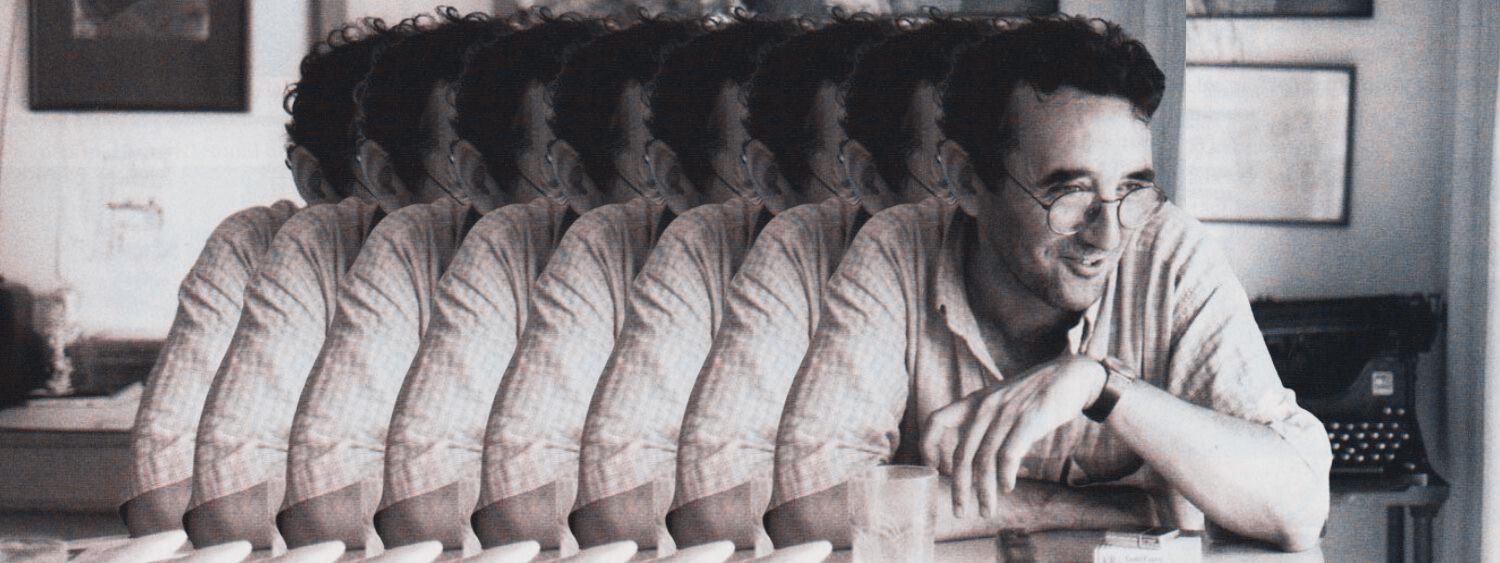

Roberto Bolaño

Twenty Years After His Death, Aaron Shulman Unpacks the Legacy of the Chilean Poet and Novelist

“We never stop reading, although every book comes to an end, just as we never stop living, although death is certain.” This certain death came tragically early for the Chilean poet and novelist Roberto Bolaño, writer of that lapidary sentence, who died twenty years ago this month at the age of 50.

In the years after his death, though, his literary afterlife grew into one of the most extraordinary in recent memory, especially for an artist who wrote mainly about desperate poets and obscure writers—not material usually predictive of strong sales or worldwide fame. A writer with avant-garde origins who worked in almost total obscurity for most of his career, Bolaño somehow emerged as the first global publishing phenomenon of the 21st century, leaving behind a large body of posthumous work that is still expanding and a life story shot through with mythos and confusion.

Today, what might seem almost as surprising as Bolaño’s extraordinary success, is the fact that two decades after his death no one has yet written a biography of him.

A cradle-to-grave tome is a rite of passage for an author of Bolaño’s stature. Richard Ellman’s massive biography of James Joyce came out 18 years after his death. The first of many biographies of Sylvia Plath was published 13 years after her suicide. Bolaño’s idol Jorge Luis Borges saw biographies in Spanish and English begin to appear just over a decade after his death.

More recently, the death-to-biography cycle seems to be accelerating. D.T. Max’s biography of David Foster Wallace appeared four years after his suicide. Blake Bailey’s biography of Phillip Roth came out three years after his (before being disowned by its publisher because of a scandal worthy of a Roth novel). And some biographies appear while the author is still alive, like Gerald Martin’s doorstopper on Gabriel García Márquez, a Latin American author whose wild international success prefigured Bolaño’s own, but who was emphatically not his idol.

Bolaño somehow emerged as the first global publishing phenomenon of the 21st century, leaving behind a large body of posthumous work that is still expanding.

Why isn’t there yet a Bolaño biography? Does it matter that there isn’t? And more broadly, what is Bolaño’s legacy today? I spent six weeks this spring trying to answer these questions on Zoom calls to Mexico, Chile, Australia and the United States, and interviewing people in Barcelona who knew Bolaño during the quarter century he lived in Catalonia, Spain.

I found a few answers, and also lingering ambiguities. But as if prophesizing his own future, Bolaño had already warned of this. “It’s hard to talk about emblematic figures,” he wrote in an essay found among his papers after his death, “who might serve as a totem between the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries.”

*

The one thing everyone I spoke to agreed on—while disagreeing about plenty else—was that Bolaño’s life would make for a rich biography. Born in Chile in 1953, his family emigrated to Mexico City when he was 15. There he co-founded a rabble-rousing poetic movement that positioned itself against the literary establishment, disrupting readings by grandees like Octavio Paz.

In 1973, Bolaño was back in Chile during the overthrow of the Allende government, and he was imprisoned and narrowly escaped execution. In 1977, he followed his mother and sister to Spain, where he worked odd jobs, including as a salesman of cheap jewelry and campground caretaker, while quietly and determinedly creating a literary universe all his own. This is the other point of consensus about Bolaño: his singular body of work.

In his literary criticism Bolaño wrote often of the role of courage—and its dark sibling, cowardice—in the lives of writers. He loathed anyone who sold out artistic or political ideals, and he upset more than a few people with his cutting categorical judgments. The Spanish word insobornable—“unbribeable,” literally, but usually translated as “incorruptible”—is an adjective people who knew Bolaño often use to describe him. This uncompromising quality of mind and heart led him to take true risks, both formally and thematically, with no promise of artistic or commercial success.

There are the risky story lines, from fascist poetic skywriting in Distant Star to the hard-to-read accounts of femicide in Juárez in 2666. Risky first-person narrators, from the compromised (read: bribeable) priest of By Night in Chile to Amulet’s exiled Uruguayan “Mother of Mexican Poetry,” trapped in a bathroom stall of the National Autonomous University of Mexico during the army’s siege in 1968. Risks in structure, from the encyclopedic entries of the slim Nazi Literature in the Americas to the tripartite, choral sprawl of The Savage Detectives. Risks in tone, the author walking a tightrope between earnest moral inquiry and flashes of hilarity. And risks in figurative language that can twist meaning almost to its breaking point, burning unforgettable images into a reader’s brain, like: “The sky, at sunset, looked like a carnivorous flower.”

Bolaño took all these risks while living just a train ride away from Barcelona, the nerve center of Spanish publishing, yet he had been in Spain for nearly 20 years before an established press, Seix Barral, finally took a risk on him, publishing Nazi Literature in 1996. When I asked Jorge Herralde, who became his longtime editor at a different publisher, Anagrama, if he suspected Bolaño would break out to the extent that he did, he joked, “I could respond that it was a sure thing, but naturally, that’s not true.”

Sitting at an outdoor café just a few blocks from Anagrama’s offices this spring, Valerie Miles, an American editor and translator who is a fixture in the Spanish-speaking literary world and co-founder of Granta en Español, told me, “There’s a lot of speculation about Bolaño’s life, a lot that’s not known yet about him.” She is one of the few people who has had access to the immense archive—over 14,000 pages—Bolaño left behind. “He didn’t have a computer [in the 1970s and ’80s], so he had notebooks and his pen and paper and mechanical typewriter and paper. There’s a whole bunch of stuff.” Much of the material is autobiographical, Miles said, and offered insights into his inner life. “He kept diaries.”

Miles’ immersion in the archive began in 2008 at the request of Bolaño’s widow, Carolina López, who stunned Barcelona’s literary establishment by moving her husband’s estate from the most famous agency in the Spanish-speaking world, the Balcells Agency, to global giant, The Wylie Agency. Miles acted as interpreter for Andrew Wylie when he visited Barcelona. Years later, López would break with Bolaño’s publisher, Anagrama. Long before this, she had already had a falling out with his close friend, the critic Ignacio Echevarría, who had shepherded the manuscript of 2666 to publication.

Some members of Bolaño’s inner circle believed that López had made these changes because of their friendship with a woman the author was apparently involved with near the end of his life. López denied these claims, stating publicly that her only motivation was to do what was best for her husband’s legacy, both editorially and financially, and that meant finding a different publisher.

It was in this heated atmosphere that Miles worked secretly, for several years, to inventory the Bolaño archive and assess newly discovered manuscripts. Her painstaking work culminated in a 2013 exhibition of pieces from the archive, a fragmented biography of sorts in a museum-like format for which Miles was the co-curator.

But in the decade since then, López has kept the archive closed and restricted rights to quote from unpublished material. The tensions and limitations around Bolaño’s estate—and perhaps also the costs of extended research visits to Chile, Mexico, and Spain that a proper biography would require—have discouraged several would-be biographers from taking on one of the most significant writers ever to come out of Latin America.

*

I wrote to the Wylie Agency to request an interview with Carolina López, though I wasn’t especially hopeful that it would happen. In recent years, she has granted few interviews; she is a private person wary of the spotlight, and journalists like me are naturally after new information to make public.

Yet to my surprise, within a day of my request being forwarded to her, López agreed to a written interview. I’m not quite sure why. Perhaps because I’m an outsider in the Barcelona publishing world, or perhaps because I had expressed my long-time admiration for Bolaño. In any case, she wasn’t put off by my nosy questions.

When I asked why the archive isn’t open for research, López was candid. For his widow, Bolaño’s legacy isn’t only literary, but a family matter too—and a painful one. “It’s difficult to explain how devastating his death was for my children, aged two and 13,” she told me, “not to mention what it meant for me. I didn’t even have time to grieve, given that my priority was my children.”

Then came the Bolaño boom in the English-speaking world, complete with widely publicized falsehoods about Bolaño having been a heroin addict and having lied about his presence in Chile during the coup (friends in Chile have confirmed that he was there). “All the garbage in the media, the lies, even stating that we were separated, complicated the mourning process for the family. We all needed professional help to process the level of suffering and to keep going… All this has left us needing protection and with a great sense of distrust with everything related to Roberto, including, of course, visits to the archive.”

In 2013, López filed several lawsuits for “violations of intimacy and honor” relating to statements that had appeared in different articles and documentaries. Then, in 2018, she sued Ignacio Echevarría, who had publicly feuded with López after publishing an article in which he discussed aspects of Bolaño’s personal life. (The suit is still working its way through the glacially slow Spanish judicial system.)

As time passes, Echevarría pointed out, the people who knew Bolaño personally are dying. “The longer the biography is delayed, further important sources will be lost.”

Sitting in a plaza in Barcelona’s Galvany neighborhood, Echevarría spoke about Bolaño with the fondness of a good friend and the admiration of a passionate critic. “He’s a writer who changed the paradigm of the Latin American author,” he said. “Every time I fall into Bolaño’s work again, he dazzles me.” The court battle has been a stressful experience for him. “No one wanted to fight,” he lamented. “I’d never had a legal problem in my life.” Despite his troubles, he managed to have a chuckle at his situation. “If I had known what I was getting myself into, maybe I wouldn’t have had such a need to say things!”

As time passes, Echevarría pointed out, the people who knew Bolaño personally are dying. “The longer the biography is delayed, further important sources will be lost.” What if a biography were written without permission from Bolaño’s estate? After all, plenty of “unauthorized” biographies of public figures appear every year.

Echevarría agreed that this was possible, but would be lacking in depth and detail compared to a work that could freely quote Bolaño’s diaries, letters, and published works. A determined biographer could make a first go of it for future biographers to build on, if and when the archive does eventually open. López says she will leave that decision to her children, although she revealed, “In a few years the archive will have a destination, probably a public one.”

*

Has the lack of a biography been a bad thing for Bolaño’s legacy? In recent years, the cult author’s visibility has declined. If we place the ecstatic high-water mark of peak Bolaño at 2008, following the posthumous publication of 2666 in English, it’s perhaps inevitable that he feels a less imposing a figure now that so many years have passed.

Meanwhile, in certain corners of academia critics grumble about Bolaño being overrated; and in parallel, the many posthumously published works may have prompted readerly fatigue among some fans, and perhaps bafflement for people new to Bolaño’s interconnected literary universe who don’t find the right place to start. Even so, his books keep selling in 35 languages around the world. A biography would introduce him to new readers, suggest fresh approaches to his work and life, and revitalize the conversation about him. But Bolaño himself might not have cared either way.

Jonathan Monroe, Cornell professor and editor of Roberto Bolaño in Context, reminded me of a passage from Amulet, in which the author lampoons the idea of artistic immortality and satirizes literary fads: “Vladimir Mayakovksy shall be reincarnated as a Chinese boy in the year 2124. Thomas Mann shall become an Ecuadorian pharmacist in the year 2101… For Marcel Proust, a desperate and prolonged period of oblivion shall begin in the year 2033… Jorge Luis Borges shall be read underground in the year 2045. Vicente Huidobro shall appeal to the masses in the year 2101.” That sound you hear is Bolaño laughing.

A delayed biography could potentially allow the turmoil around the author’s legacy to die down as trends shift, so that we can more clearly appreciate his impact. As Valerie Miles said, “We editors know it’s not a bad thing making people wait.”

Reputations and book sales will always wax and wane, but Roberto Bolaño’s work seems destined to stand the test of time (it already has so far) and the lack of a biography for now. As if to confirm this, one day I met an old friend of Bolaño’s at the café of the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, which exhibited the archive in 2013. Sure enough, at a table near us a young woman was reading 2666. When I pointed this out to him, he said, “See, that’s what matters. That’s all that matters.”

Aaron Shulman

Aaron Shulman is the author of The Age of Disenchantments: The Epic Story of Spain’s Most Notorious Literary Family and the Long Shadow of the Spanish Civil War (Ecco/Harper Collins, 2019). He lives in Barcelona with his family.