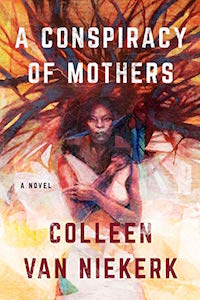

The Complex Freedom of Creating Art as a Black Woman in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Colleen van Niekerk on Writing After Enforced Silence

When I was a kid growing up in apartheid South Africa, art was something that white people did. They owned it, were custodians of it, they were the designated ones capable of producing it. In our home, one of my brothers provided the reggae of Peter Tosh, Steel Pulse and others. In Cape Town, my city, we had graffiti, Public Enemy, liberation struggle posters and District Six—The Musical. We had B-Boys and an assortment of horn players, all of whom were beloved sons of the Cape. But while Eddy Grant sang the cheeriest of protest songs called “Gimme hope Jo’anna,” it was whites who had visual art and post-modernism. They arranged arts festivals and had the imposing theater downtown that staged operas and plays. They wrote books.

We were minstrels on show at Tweede Nuwe Jaar, the day after New Year’s, an annual celebratory day in Cape Town of parades, band music, painted faces and flashy suits. This day existed because it was traditionally the single day of the year that our slave ancestors had off from work. Yes, the year. One could argue who the festivities of that day are truly for now, but, back in the day, could there be a more revealing way of describing our worth to white society as artists? Entertain us, be a spectacle, but for God’s sake don’t think you can produce intellectually rigorous, “real” art. And do all of this on your day off.

I’ve been writing since I was 10, but it’s taken me more than 30 years to call myself a writer, to own the descriptor with ease and without insecurity. This could only come after shaking off what this messaging throughout my youth bred, and what I’ve seen in some other women of color: a crippling sense of insecurity about my worth. These messages about literature and art, in a place that couldn’t even afford me the decency of a proper name for my cultural and ethnic group (we were classified as “colored” by the apartheid government), made a formidable wall that stood between me and ownership of what I can do.

Instead, I had learned in the 80s that being an artist of color in South Africa meant living an insecure, fraught existence despite the adulation some might give. There were coloreds who wrote novels but they were few. After all, the government didn’t really like what they had to say.

Stories are ours, and so is the act of storytelling. Those who are part of the African diaspora know this full well.These are different times; how different is a question of degrees which depends on context. The momentum of the last few years has, at least, provided space in public discourse for us to raise awareness of the deeply personal nature of many issues of social justice. Younger generations of color have a far lower tolerance for directives that tell them they’re inferior. It’s about time.

But there is, in tandem with all of this—especially in those of us who are older women of color—the deep wound we often deal with that comes with that contested sense of worth. Society told us for decades to accommodate less attention and less care, that that is all we’re good for. We are not enough, we’ve been told. I often look at TV shows or movies with white female leads and wonder what the extent of change to the entire story line would be if that character was Black, was dark-skinned, was Brown. The answer usually isn’t favorable. In this way, and others, signals come hard and fast that we make people uncomfortable. Yet it is not weakness to set boundaries, acknowledge one’s vulnerabilities, ask for what you need, and refuse to accept society’s often callous treatment as a shameful, personal failure.

The path through this for me lies in the simple act of putting pen to paper. It enables a particular, exhilarating freedom; an opportunity to speak on my own terms. Over many years, in snatches of time here and there that became longer nights and earlier mornings, I wrote. In long hand, on laptops, Post-It notes and phones, on planes and trains, I wrote. I let the page lead me to where I needed to go. I let it be the place where I figured out what I had to say, and how I wanted to say it. I decided that, in the end, I had to make up my own mind about art and belonging.

It meant writing myself into an understanding of the craft over a long and circuitous journey, and finding along the way both the community and the confidence I needed to set aside conventions that told me what I was supposed to say, and that my voice had little value.

For Black and Brown women, the justification for our own persecution—which has a twisted and complex history of its own, as the author Ruby Hamad deftly outlines in White Tears/ Brown Scars—often boils down to accusations of having too much lip. We’re too unkempt, too ethnic or ghetto. We’re too angry, and besides, what could we possibly know? In this way, we are told we are inherently responsible for the strangulation of our ambitions and the multi-generational effect that has had on the physical manifestation of worth (our earnings, our wallets).

If your writing is through the lens of the Black experience, especially as a woman, it is essential not to take on board the discomfort, the judgement, the savior complex, the racism, or aggression of others—that’s their path, not yours.Growing up in a society obsessively focused on hair, nose, and eye color (because under apartheid, this determined the racial classifier in your identity document, which in turn established every single facet of your life), I learned that I had to be a zealous guardian of my value. Stories are ours, and so is the act of storytelling. Those who are part of the African diaspora know this full well. Story for us is oftentimes generational memory; oral traditions are far older than the written word, and literature, by extension, is not the exclusive, overpriced property of those of a certain age, ethnicity, social standing or graduate program. To women of color weathered after decades of being spoken over, spoken for, flat out ignored, or taken for granted, women working to make room for different kinds of stories and conversations, society should ask: what do you have to say? What have our conventions silenced out of you?

This brings us to the territory of our experience, and our observations, the substance of what we choose to craft into words. It is difficult, when looking at the body of English literature, especially those works considered classic, to see ourselves on the page as full-bodied equals, and not the help, the temptress, the conquered, or the mad woman in the attic. But frankly, so what? Freedom on the page is release, it is the opportunity to create what didn’t exist before, to decide what to carry and what to leave behind. Treating artists and what they have to say as second-class doesn’t make them any less significant. If that is ever in doubt, consider hip-hop.

If your writing is through the lens of the Black experience, especially as a woman, it is essential not to take on board the discomfort, the judgement, the savior complex, the racism, or aggression of others—that’s their path, not yours. Finding the voice to articulate what you have to say and expressing your worth on paper, or out loud, is no mean feat. Meanwhile, the question for those in broader society is simple: when the person speaking is a woman of color, are you prepared to listen?

______________________________________________________

Colleen van Niekerk’s novel A Conspiracy of Mothers is available now via Little A.