The Coming-of-Age Tale As Societal Critique: Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar at 60

Heather Clark on One of the Defining Novels of the 20th Century

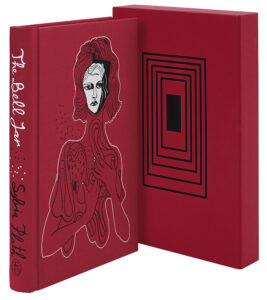

Illustrations: © Alexandra Levasseur, 2022

From the time she was a young child, Sylvia Plath wanted to write. Her first poem was published when she was just eight years old in a Boston newspaper, and she began writing an early novel, titled Stardust, when she was nine. She published regularly in her school magazines; by the time she was eighteen, her poetry and fiction had appeared in the Christian Science Monitor and Seventeen after more than fifty rejections.

Plath became the star of the English department at her undergraduate alma mater, Smith College, where she won top prizes and graduated summa cum laude in 1955. A Fulbright Scholarship to Cambridge University followed, and, after graduating in 1957, she began publishing poems in the New Yorker and other prestigious literary journals. Her first book of poetry, The Colossus, received excellent reviews when it came out in 1960. Throughout this time Plath aspired to write a novel, but the form eluded her until she was nearly thirty.

Plath wrote The Bell Jar in the spring and summer of 1961 when she was living in London with her husband, the British poet Ted Hughes, and their one-year-old daughter. She had been working in fits and starts on a novel about her early years at Cambridge, titled Falcon Yard, but it never caught fire. Then, after a brief hospitalization for an appendectomy in February 1961, The Bell Jar came to Plath in a rush. The routine hospital stay unlocked other, more traumatic memories of her experience as a psychiatric patient at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, in 1953. Each morning, Plath wrote fluently and without shame about this painful period of her life.

The Bell Jar tells the story of a young woman’s breakdown and recovery, but it is also a devastating critique of a paternalistic psychiatric system that regarded ambition in women as neurotic.

In 1953, Plath had won a coveted spot as a summer guest editor at Mademoiselle magazine in Manhattan. She spent the month of June contributing to features, attending fashion events, and helping to manage the magazine’s day-to-day production. The pressures were intense, and the experience left her exhausted and disillusioned. Was this all Plath could hope for as an aspiring woman writer? Would her work be limited to penning fashion captions, like the one she had written for the August Mademoiselle about the “astronomic versatility of sweaters?” Heatwaves, food poisoning, and the attentions of predatory men also left their mark on Plath’s psyche that summer.

Illustration © Alexandra Levasseur, 2022

Illustration © Alexandra Levasseur, 2022

When Plath returned home to Wellesley, Massachusetts, at the end of her internship, she learned that she had been rejected from Frank O’Connor’s writing class at Harvard Summer School. She was already dejected after her month in New York and the news catapulted her into a full-blown depression. Plath was unable to read or sleep, and became convinced she had lost her ability to create art. She saw a psychiatrist in July and experienced her first rounds of outpatient electroshock therapy at Valley Head Hospital, outside Boston.

The badly administered shock treatment traumatized Plath. Her depression worsened, and in late August she hid in her family basement and attempted suicide with sleeping pills; her brother found her semi-conscious but alive three days later. Suicide, she later wrote to a friend, had seemed preferable to a life of torturous treatments inside a mental hospital. Better to end it all, she reasoned, while she would still be remembered as a success. Plath eventually recovered at McLean Hospital where she met an influential psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Beuscher. Beuscher prescribed further shock treatments, but these were administered more humanely. At McLean, Plath’s mental health improved and she returned to Smith in early 1954.

Plath fictionalized nearly all of these experiences in The Bell Jar, which is narrated by Esther Greenwood, a summer intern at Ladies’ Day magazine and an aspiring writer who attempts suicide after suffering a breakdown. Plath based Esther loosely on herself: both were raised by a widowed mother in Massachusetts; both were star writers at a women’s college; both dated an imperious medical student; both suffered breakdowns, attempted suicide and recovered at an upscale mental hospital outside Boston.

The similarities between Plath and Esther were so strong that Plath’s London publisher, Heinemann, warned her about potential libel issues. (As it turned out, they were correct. Jane Anderson, a woman who had known Plath at McLean, argued that the novel contained an unflattering portrait of her and sued the Plath Estate for libel in the 1980s.) Plath dismissed their concerns, but published the novel under a pseudonym, Victoria Lucas.

Still, Sylvia Plath is not Esther Greenwood. Plath treats Esther with gentle irony in much the same way James Joyce treats his youthful alter ego, Stephen Dedalus, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man—a novel which The Bell Jar draws upon and satirizes. Plath knew and loved the novels of James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf, as well as the poetry of T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats.

These modernist writers left their mark upon The Bell Jar, which, like The Waste Land and Dubliners, contains images of paralysis, decay, death-in-life, and urban desolation. Plath’s many literary allusions to Joyce and Eliot, in particular, underscore the fact that The Bell Jar—whose title alludes to a similar image in works by Elizabeth Bowen and Henry James—is a finely crafted novel rather than a mere roman-à-clef. In fact, The Bell Jar refuses to fit neatly into any single genre: it is feminist protest, Cold War history, medical exposé, Bildungsroman, recovery narrative, and quest.

In the mid-1950s, breakdowns, mental hospitals, and suicide attempts had seemed to Plath too taboo, too shameful, to explore in a novel of her own. By the early 1960s, however, Jennifer Dawson and Shirley Jackson had published successful novels about psychological breakdowns. Plath admired Jackson’s The Bird’s Nest (1954), and began to think more seriously about mining her own psychiatric history in a book. “I am a fool if I don’t relive, recreate it,” she wrote in her journal in June 1959. Plath was more confident, too, about speaking out against the cultural and medical injustices that had threatened her sanity.

In 1950, she had blamed herself for her mental problems—”unaccountably I am sick and sad,” she wrote in her journal—but by 1961 she recognized that conservative aspects of American Cold War culture may have exacerbated her depression and contributed to her 1953 breakdown. In The Bell Jar, she addressed the repressive cultural conditions that held women back and limited their opportunities, independence, and power. And it was not just women who suffered in such a culture. The first sentence of The Bell Jar—“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York”—announces that, in Eisenhower’s America, dissidence, including Esther’s own, will be punished by electric shock.

The Bell Jar is Esther’s (and Plath’s) attempt to forge her own destiny and tell her own story in a society that dismisses both the ambitions and the suffering of women.

The Bell Jar tells the story of a young woman’s breakdown and recovery, but it is also a devastating critique of a paternalistic psychiatric system that regarded ambition in women as neurotic. The male psychiatrists who treat Esther have little understanding of the gendered pressures that have contributed to her breakdown: the dismissive and condescending Dr. Gordon responds to Esther’s serious need for therapeutic help with a wistful memory of pretty girls stationed at her college during the war. (Plath’s critique of psychiatry was timely: in 1953, there were 559,000 psychiatric inpatients in American mental hospitals—an all-time high.)

Plath herself treats Esther with the kind of empathy and perceptiveness that her male doctors lack, but never glamorizes Esther’s depression or suicide attempt. Instead, she shows how mental illness robs Esther of autonomy and agency. Plath mocks the tabloid news articles that exploit Esther’s suffering and sensationalize her suicide attempt for profit. (She would take similar aim at the “peanut-crunching crowd” in her 1962 poem “Lady Lazarus.”) She hints that Esther’s sickness may be an understandable response to society itself: “sick,” warmongering, sexist, homophobic, and racist.

Illustration © Alexandra Levasseur, 2022

Illustration © Alexandra Levasseur, 2022

“Give us a smile,” a male fashion photographer at Ladies’ Day tells a grimacing Esther, who forces herself to look happy for the photo—and, implicitly, the male gaze. “At last, obediently, like the mouth of a ventriloquist’s dummy, my own mouth started to quirk up.” Plath suggests throughout The Bell Jar that revealing one’s pain, or nonconforming self, is not permissible in midcentury America: gleaming surfaces hide the rot within. Plath makes this theme brilliantly clear in a memorable passage about the avocado-and-crabmeat lunch that sickens the Ladies’ Day guest editors:

I had a vision of the celestially white kitchens on Ladies’ Day stretching into infinity. I saw avocado pear after avocado pear being stuffed with crabmeat and mayonnaise and photographed under brilliant lights. I saw the delicate, pink-mottled claw-meat poking seductively through its blanket of mayonnaise and the bland, yellow pear cup with its rim of alligator-green cradling the whole mess.

Poison.

The Bell Jar is Esther’s (and Plath’s) attempt to forge her own destiny and tell her own story in a society that dismisses both the ambitions and the suffering of women. Plath suggests it is no accident that a cerebral, aspiring writer suffers a breakdown after working within a fashion and beauty industry that exploits female insecurity. When Esther throws her tight-fitting wardrobe off the roof of the Amazon hotel, she is protesting women’s objectification and powerlessness in mid-century America. Although Esther is a top student and brilliant writer, she worries that her future will be that of “a waitress or a typist.

But I couldn’t stand the idea of being either one.” Nearly every option available to her means subservience to men. Esther’s sometime boyfriend, Buddy Willard, confirms this notion when he tells Esther that his mother is always saying, “What a man is is an arrow into the future and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from.” The idea makes Esther fume. “The trouble was, I hated the idea of serving men in any way. I wanted to dictate my own thrilling letters.” In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce famously wrote about Stephen Dedalus’s struggles to evade the societal nets that tried to hold him back as he attempted to fulfill his literary vocation. Esther must perform a similar feat, but those societal nets are tighter and stronger for a woman. She barely escapes alive.

After Plath and Hughes separated in the autumn of 1962, Plath became determined to support herself and her children through her writing. Though Hughes was paying her monthly child support, she did not want to depend on his money. A proud woman, she hoped to live a vibrant literary life in London on her own terms. “All I want is my own life,” she wrote to the poet Bill Merwin in November 1962, “not to be anybody’s wife, but to be free to travel, move, work, be without check.”

That autumn, Plath had written many of the Ariel poems that would make her name, but she knew poetry was not the route to financial stability. She hoped The Bell Jar would be a bestseller when it was published in January 1963, but the novel’s first reviews, which ranged from good to excellent, did not translate to high sales. This let-down, as well as other trying events in Plath’s life that winter, brought on a severe depression. This time she did not survive: Plath died by suicide on 11 February, 1963.

The Bell Jar went on to become one of the best-known American novels of the twentieth century, and a touchstone of young womanhood. If only Sylvia Plath had lived to see its phenomenal success.

__________________________________

The Folio Society edition of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, introduced by Heather Clark and illustrated by Alexandra Levasseur, is exclusively available from foliosociety.com

Heather Clark

Heather Clark earned her bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Harvard University and her doctorate in English from Oxford University. A former Visiting Scholar at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing, she is the author of The Grief of Influence: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes and The Ulster Renaissance: Poetry in Belfast 1962-1972. Her work has appeared in publications including Harvard Review and The Times Literary Supplement, and she recently served as the scholarly consultant for the BBC documentary Sylvia Plath: Life Inside the Bell Jar.