When I was attending the university, I had a friend from the Castles named Lorella. We both took courses in classical Arabic at the Università La Sapienza in Rome, but the truth is, I never really learned Arabic.

Nevertheless, studying that language at least allowed me to understand the meaning of my name, Leila: night.

Lorella, on the other hand, was good at Arabic. She was always raising her hand in class, and the professor praised her for her excellent Egyptian accent.

Lorella . . . Everything began with her.

Lafanu Brown had yet to appear in my life, but the destiny that would lead me to her had already put itself into motion. And the first piece of the puzzle was none other than Lorella.

I have no idea what became of my old university friend. I should seek her out on Facebook or Instagram, but I don’t dare. I don’t want to look at her wrinkles, the wrinkles of a woman in her forties, and see my own. And besides, it would be humiliating to discover that she actually learned Arabic, whereas I didn’t.

I don’t remember much about her appearance. The only feature that has remained in my brain is her large mouth, an African-looking mouth, bigger than mine, and I really am an African. Or rather, my parents really are Africans; I’m just an offshoot. A peculiar blend of Rome and Mogadishu, the issue of a scruffy couple who fled dictatorship in Somalia and instead of taking refuge in Paris or London headed for Rome because the year before, while there on their honeymoon, they’d watched the Ethiopian distance runner Abebe Bikila win the marathon barefoot in the legendary 1960 Summer Olympics, held in Rome. So my parents told each other that they too could win the marathon of life, or at least return to some form of the normalcy that the dictatorship of Big Mouth—which was what everyone called the Somali dictator—had taken from them. And I was their new beginning. A chubby baby with big, astonished eyes who nevertheless was unable completely to erase the melancholy from their faces. Maybe that’s why, from time to time, I’m melancholy too. In exile from a country that has basically never been mine.

But as I was saying, Lorella’s lips were decidedly more African than mine. Not that she used them very much—she talked so little! But I remember finding her silence very good company.

One day in class, out of the blue, she asked me if I’d ever been to Marino, a hill town near the city, one of the Roman Castles.

I said I hadn’t.

And she said, “Too bad for you. Next weekend’s the grape festival, why don’t you come? My mother will be happy to put you up.”

“It’s a deal,” I said.

We shook hands, and so the following weekend I went to Marino. For dinner, we had pasta with tomato and basil, prepared by Lorella’s mother. Very simple, very tasty, served with lots of Parmesan.

At one point in the meal, Lorella’s mother poked me with her elbow and said, as though letting me in on a secret, “We eat a lot during the festival, so it’s best to keep things light this evening. Otherwise you won’t have room tomorrow for all the good things the festival puts out every year. We’ll eat porchetta and drink plenty of wine. A real treat!”

I smiled out of politeness. But my smile was forced. A bit worried, even.

I’m a Muslim. Porchetta—pork roast—and wine are haram. They surely weren’t right for me.

But I didn’t have the nerve to tell Lorella’s mother I didn’t eat or drink any of that gaal stuff.

Gaal, what an ugly word. It means “infidel,” someone who’s not in our club, not from our “tribe.” It’s a Somali word I used a lot when I was twenty, but which now, well into my forties, I find horrifying because it separates me from other people. But at the time, I felt so different, so “other.” And I remember my shame at always being the person who gets noticed because she doesn’t eat this or drink that. I was always the odd one, the one who obeyed incomprehensible rules. I was, in short, ashamed to be myself. And so I didn’t have the nerve to blurt out to Lorella’s extremely blond mother that I was an Italian girl but different from her. And that I would prefer a cheese sandwich.

If that were to happen today, maybe I’d speak. But it was 1992. My cultural difference weighed on me. I didn’t know how to make sense of it.

It was so hard to have to explain myself all the time. Explain the skin, the kinky hair, the big butt. My melanin was always getting in the way. And I always had to respond to stupid remarks such as, “Ah, but you speak good Italian.”

Well, maybe that’s because it’s my native language, damn it! I certainly did speak good Italian. Often better than some who considered themselves 61 more Italian than me. But people couldn’t comprehend the fact that we—other Black Italians and I— were there among them. In 1992, we were invisible. We were specters.

We were there in the society, we immigrants and children of immigrants, and it wasn’t as though we had just arrived, but the majority of the population knew little or nothing about us. They didn’t know how to place us. They got us mixed up and called us foreigners. As far as Italians were concerned, we— whether Muslims or Sikhs or Hindus or Orthodox Christians—were simply outsiders, aliens, certainly none of theirs!

Italy hadn’t noticed that we were farther along and already mingling worlds, ours and theirs. That Italy, a nation born only in the previous century, was already pulsing with our migrated blood. Italy, running naked and mad between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.

But I didn’t have the nerve to say all that to Lorella and her mother. To say that I would never eat pork or drink wine because I wanted to stay connected to my ancestors somehow. They had taken their first steps in the fabulous Land of Punt—in Somalia, famed for frankincense, where sometime before Christ a female pharaoh, an Egyptian ruler named Hatshepsut, would go to drench herself in our heavenly perfumes. I dreamed about my ancestors every night, but they received no mention in any school I ever went to. There was so much I wanted to learn about them. What sorts of faces did they have? Did they look like me? And how did they show love? Did they kiss each other? On the mouth, on the nose? What did they dream about? How I would have liked to meet them, to read about them. And so food—that is, following our dietary laws to the letter—was the easiest way to make contact with their history, which I felt was mine as well.

Without saying anything, therefore, I went to my room and the bed that had been prepared for me.

It was a large house. And only two people lived there.

I didn’t ask Lorella about her father. Maybe he was dead, or maybe he’d run off with a lover. In any case, the two women, mother and daughter, didn’t seem to have any financial problems.

I envied them a little. And I thought about our immigrants’ apartment in the Prenestina district, where we were packed tightly together, practically on top of one another, and where I was never able to study.

Low-income housing. My mother always used to assure me, “We weren’t poor in Somalia. We had a nice house in the Skuraran quarter. I had a vegetable garden, some chickens, a mango tree, and a lemon tree. The curtains came from Zanzibar, the furniture from Milan. We could afford lots of things.” My mother clung to her opulent past. She would tell me about her family, who were dealers in fine fabrics, and especially about Daddy’s pharmacy. “All Mogadishu came to seek his advice for upset stomachs, for pounding headaches, for broken bones. Daddy knew the right advice to give to everyone. He was good at his job.” And I wanted to believe her. But then my reality had collided with another Daddy, a man whose degree the Italian government wouldn’t recognize, and who had grown severely depressed, cut off from his chosen profession. But my parents did what they could, they did their best. They sacrificed themselves for us and for the relatives they’d left behind in Somalia, to whom they regularly sent money. Mama scrubbed the floors in white people’s houses, and Daddy eventually found a job doing the cleaning at a pharmacy near our place. He’d accepted the work because going back to a pharmacy, even if only to clean it, had seemed to him like catching a momentary whiff of the paradise he’d lost. We certainly couldn’t afford any luxuries. The little money my parents earned—and this made me furious—was used to take in other “refugees” from Somalia, whom they lavished with food and attention. So if I needed a new pencil case, or if I longed for a certain blouse because all my classmates had one, my parents would say, “Don’t be selfish, we have to help others.” And at the time, since like all teenagers I was too selfish, I hated those homeless people who came in and occupied my home. They were invaders. I detested them. And even by the time I was twenty, my feelings about immigrant solidarity hadn’t changed all that much. I knew I was a bitch, and deep down inside I felt kind of proud of myself. Fortunately, as more time passed, I changed. But that night in Lorella’s house, all I could think about was how many things life had taken away from me.

I switched off the light. A bed I didn’t have to share. Finally. For two nights, I’d be able to stretch out my legs.

I often think about that night, and about how selfish I was when I was twenty years old!

But the following day, everything changed. Even though I didn’t know it yet, I was retracing the footsteps of Lafanu Brown.

__________________________________

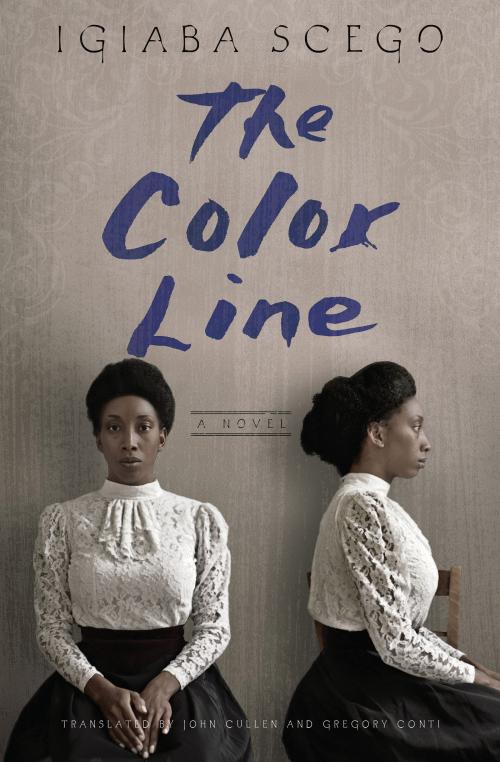

From The Color Line by Igiaba Scego, translated by John Cullen and Gregory Conti. Used with permission of the publisher, Other Press. Copyright © 2022 by Igiaba Scego. Translation copyright © 2022 by John Cullen and Gregory Conti.