The Chronicler of Asian America: Hua Hsu on Photographer and Activist Corky Lee

“We await our moment, in pursuit of the picture that Corky envisaged, a portrait of a community that is too large and too brilliant.”

It’s probably one of the most useless conversations I can have with a young person: the way things used to be. You can’t imagine the effort it once took to take a simple picture. It required not just possession of an actual camera but also the foresight to carry it around with you, not to mention lighting, manual focus, the cost of film. Nowadays I take more pictures on an average day than I did in entire years in the eighties or nineties, of things I would have never thought to chronicle back then: plates of food, funny street signs, chance encounters with friends. We are awash in images. They feel inevitable.

I’d tell this imaginary young person that we were once so starved for pictures of the world that we would study the ones we had over and over. We would horde and exchange them; entire movements grew out of photographs that captured humanity at its very worst. I would want to explain to this person that we are so lucky that Corky Lee never wavered, never seemed to feel tired or jaded. For fifty years he devoted himself to chronicling the Asian American community—a tricky proposition given the diverse complexities of the category, but he never ran from the complications of this assignment. For Corky, photography was more than the daily registration of our whereabouts. Photography was a way of seeing. And, for generations, Corky taught us how to see ourselves—as individuals and as a community.

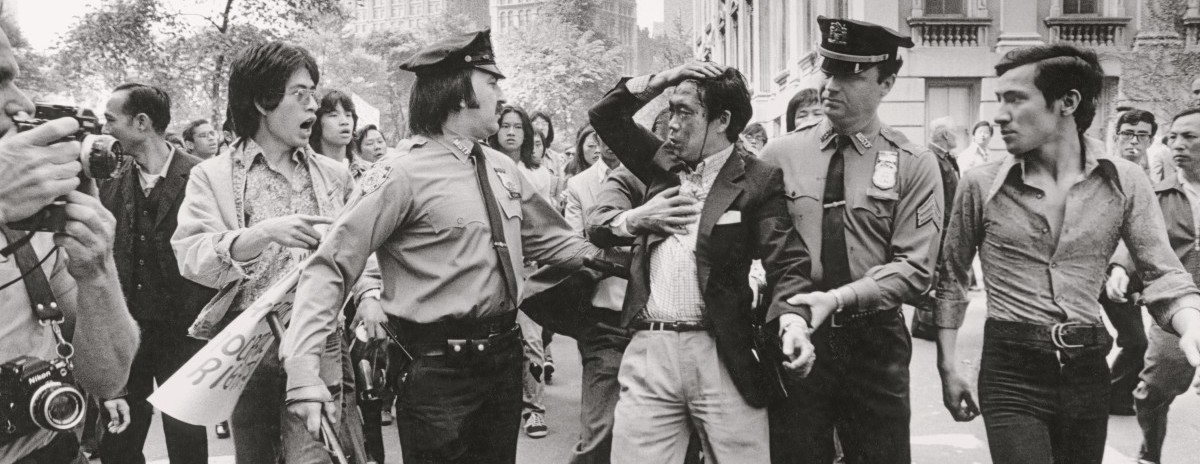

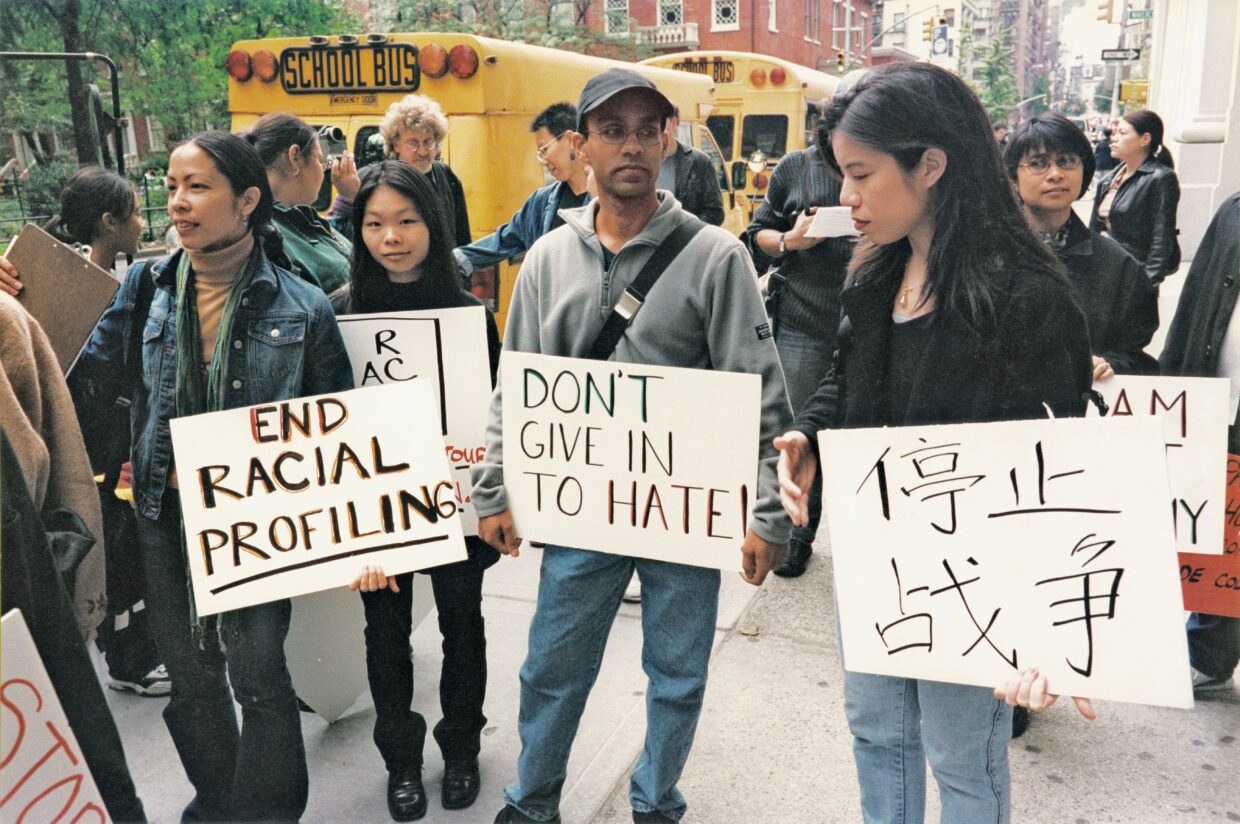

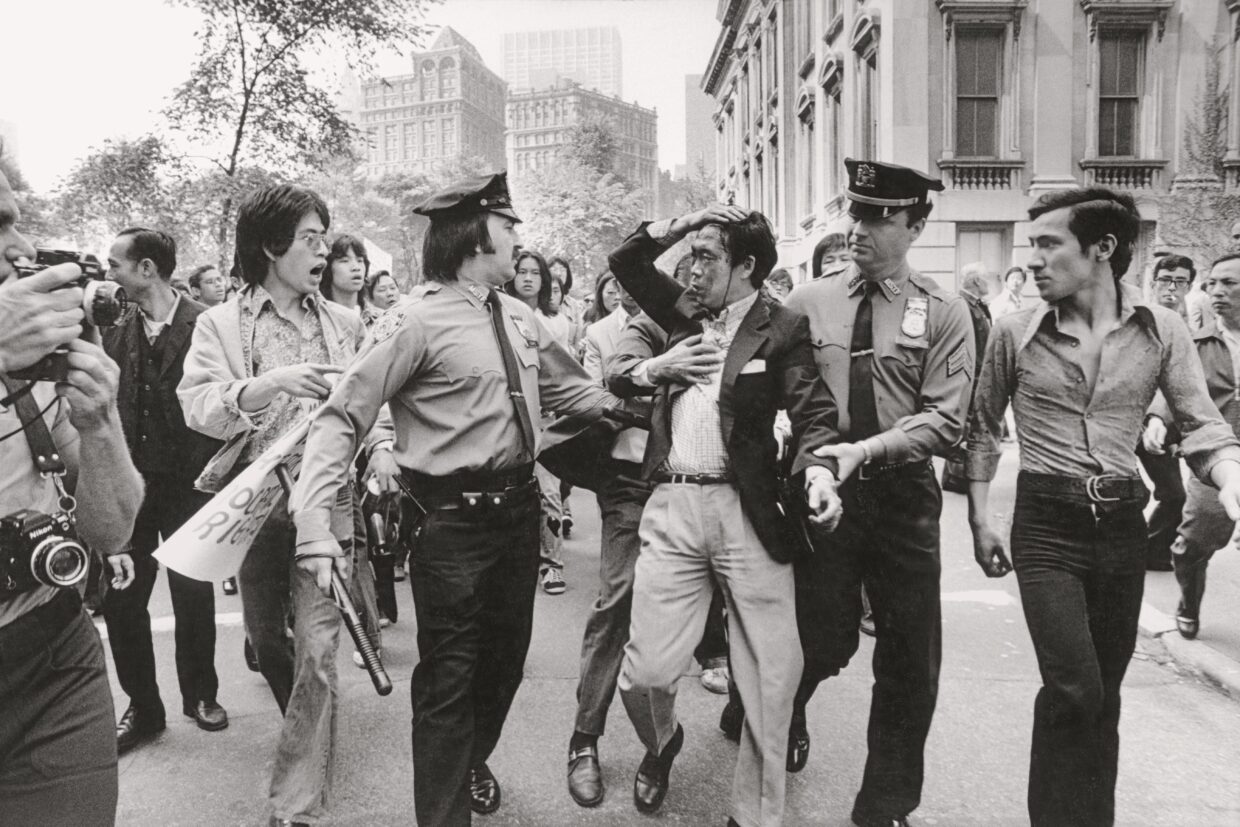

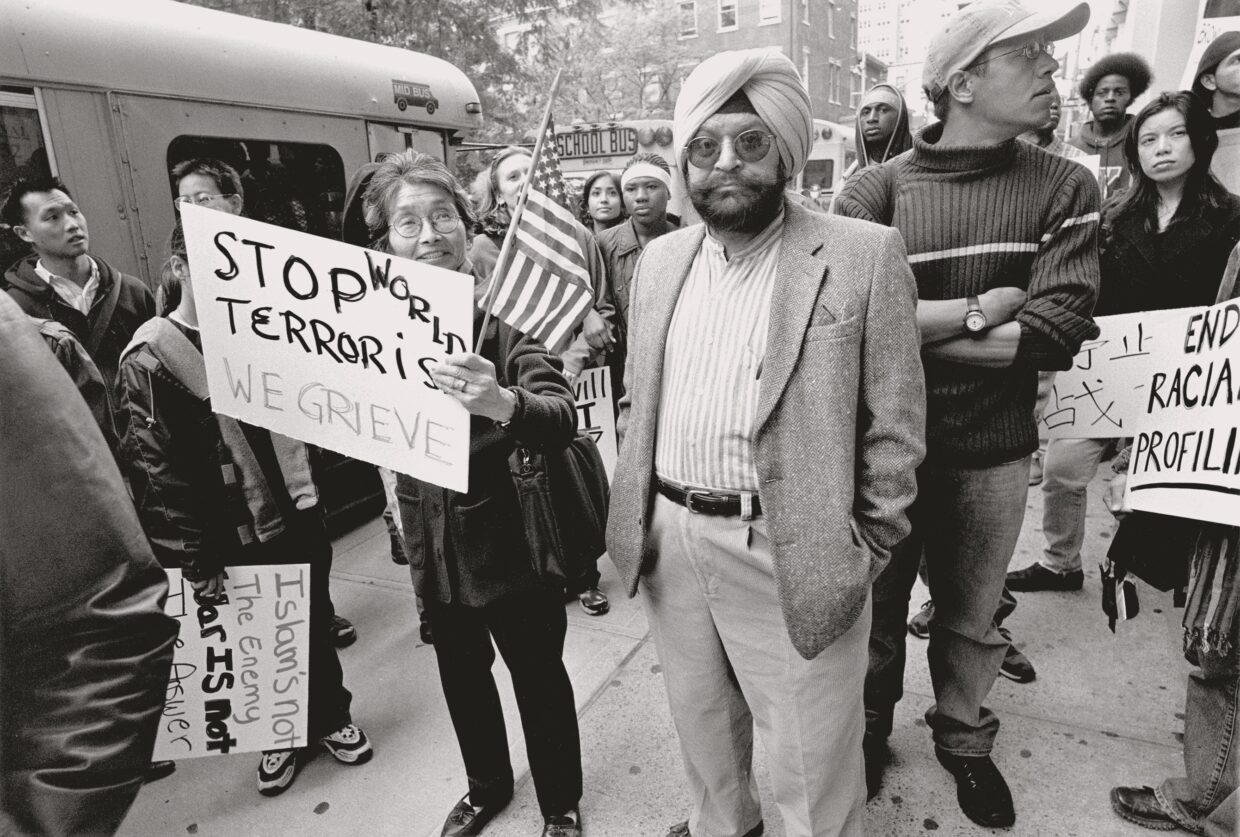

Corky was everywhere. The protests and concerts, rallies and opening-night premieres, demonstrations and parties, as well as the rehearsals and planning sessions that preceded them. He took some of the only photos that survive of Chinatown in the seventies, back when it was a nexus of activism: protests against the Vietnam War or police brutality or cruel bosses or miserly landlords. “Every time I take my camera out of my bag,” he once said, “it is like drawing a sword to combat indifference, injustice, and discrimination and trying to get rid of stereotypes.” But he was still just a photographer; he had to show up and wait for the right moment.

For generations, Corky taught us how to see ourselves—as individuals and as a community.

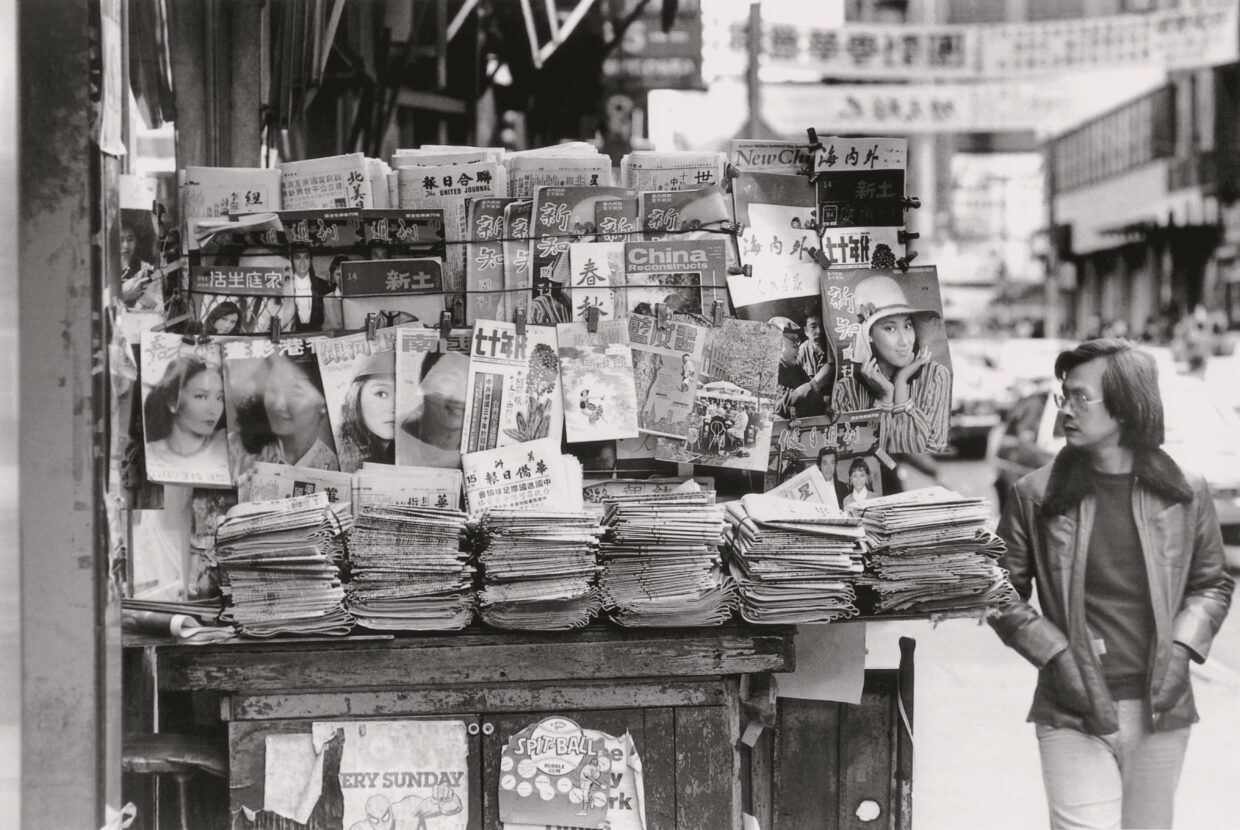

Some don’t expect to be noticed at all; they’ve been conditioned to see themselves outside of American history, even when they are central to it. These were the people of Corky’s community, the spirit that runs through his portraits of forgotten merchants, old couples showing off their cramped apartments, kids dancing and playing in the street. Pictures of restaurants, factories, cabs, newsstands, and laundries, full of people who didn’t comprehend why he was bothering to take pictures of them.

Chinatown rock gigs and beauty pageants, teenagers hanging out on the corner trying to look as cool as possible for the man with the camera. Sparsely attended readings or community meetings that suddenly seemed important since Corky had shown up to document them. Perhaps they were doing something important after all. For Corky, the commitment to community required constant renewal and reaffirmation. Each new organization or collective could be the one that changed the world.

It’s humbling to survey the range and breadth of Corky’s five decades of work, as the tight focus on Manhattan’s Chinatown widens to consider neighborhoods, experiences, and ethnicities throughout the nation. There are factions and disagreements, moments when stress is applied to any sense of common purpose. The Asian American community remains an unfinished project. But for Corky, the work that remained was a reason for hope, not despair.

My imaginary young friend, by now weary from my lecture, gives a perfunctory nod. We no longer feel invisible, the way Corky once did, even if we sometimes still feel unseen. And this young person, fed up with playing the part of a stereotype, finally scoffs. These pictures aren’t meant to anchor us to the past; they are meant as gifts for the future, too. My young friend would recognize that Corky’s gifts were his patience and curiosity.

The point of Corky’s work, they would continue, was never to dictate a single way forward. His pictures are as much about honoring overlooked visionaries and leaders as they are attempts to valorize the masses, the possibility of change that draws strangers together, across neighborhoods and generations. And this young person would leave me behind and go into the world in search of their own interpretation of community.

Back then was the same as now, it’s just the cameras that have changed. We await our moment, in pursuit of the picture that Corky envisaged, a portrait of a community that is too large and too brilliant, it can only come into focus in these beautiful, fleeting fragments.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from Corky Lee’s Asian America: Fifty Years of Photographic Justice. Copyright © 2024 by the Estate of Corky Lee, Mae Ngai, and Chee Wang Ng. Text copyright © 2024 by Mae Ngai unless otherwise noted. Photographs copyright © 2024 by the Estate of Corky Lee unless otherwise noted. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Hua Hsu

Hua Hsu is the author of the memoir Stay True, a staff writer at The New Yorker and a professor of Literature at Bard College. Hsu serves on the executive board of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. He was formerly a fellow at the New America Foundation and the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at the New York Public Library. He lives in Brooklyn, New York with his family.