There was a young woman sitting in the bar. Her name was Pearl. She was drinking gin and tonics and she held an infant in the crook of her right arm. The infant was two months old and his name was Sam.

The bar was not so bad. Normal-looking people sat around her eating pretzel logs. The management advertised it as being cool and it was. There was a polar bear of leaded glass hanging in the center of the window. Outside it was Florida. Across the street was a big white shopping center full of white sedans. The heavy white air hung visibly in layers. Pearl could see the layers very clearly. The middle layer was all dream and misunderstanding and responsibility. Things moved about at the top with a little more arrogance and zip but at the bottom was the ever-moving present. It was the present, it had been the present, and it was always going to be the present. Pearl was always conscious of this. It made her pretty passive and indecisive usually.

She was wearing an expensive dress although it was spotted and the wrong weight for the weather. She had no luggage but she had quite a bit of money. She had just come down from the North that morning and had been in the hotel just a little over an hour. She had rented a room here. The management had put a crib in the room for Sam. When they had asked her her name she had replied that it was Tuna, which was not true.

“Tuna,” the management had said. “That is certainly an unusual name.”

“Yes,” Pearl said. “I’ve always hated it.”

The hotel was close to the airport. Hundreds of hotels and apartments were close to the airport; nevertheless Pearl still felt that she was being obvious. She had never been in this city before but she felt that it was an obvious choice for a runaway. She would check out of the hotel tomorrow and go deeper into the city. Perhaps she would find a tourist home there. The home would have black shutters and a wrap-around porch. Pleasant, portly women would sit on the porch eating plates of key lime pie. She would become one of them. She would get old.

She felt Walker’s gaze burning into her back. Walker’s smart and silent gaze. Pearl’s stomach trembled. She turned violently around and saw nothing. The baby woke with a muffled grunt.

Pearl ordered another gin and tonic. For some reason the waitress did not hear what she said.

“What?” the waitress said.

Pearl raised her glass. “A gin and tonic,” she repeated.

“Certainly,” the waitress said.

Pearl often mumbled and did not make herself clear. Frequently people believed her to be implying something with her words that she was not implying at all. Words, for her, were issued with stubborn inaccuracy. The children had told her once that the sun was called the sun because the real word for it was too terrible. Pearl felt that she knew all the terrible words but none of their substitutes. Substitutions were what made civilized conversation possible. Whenever Pearl attempted civilized conversation, it sounded like gibberish. She could never find the appropriate euphemisms. Death, Walker had said, is a euphemism. But after all, the knock on the door, the messenger, the awaited guest was not always death, was it?

Pearl thought so, probably, yes.

The waitress came back with Pearl’s gin and tonic. She was a pretty girl with blond bobbed hair and a small silver cross around her neck. She bent down slightly to serve the drink. Pearl detected a faint odor of cat piss. This is not fair of me, Pearl thought kindly. Things in Florida sometimes presented the odor of cat piss. It was the vegetation.

“Why do you wear a cross?” Pearl asked.

The girl looked at her with faint disgust. “I like the shape,” she said.

Pearl thought the remark to be a little crude. She sighed. She was becoming drunk. Her cheekbones reddened. The waitress went back to the bar and stood talking with a young man seated there. Pearl imagined them in some rank room after closing hours, spreading dough over their bodies and eating it off in some bourgeois rite. Pearl spread her hand and pressed her fingers hard against her cheekbones. She felt guilty and annoyed.

She also felt a little silly. She was running away from her home, from her husband. She had taken her little baby and carefully arranged a flight away in secret. She had boarded a plane and traveled twelve hundred miles in three hours. The deception that had been necessary! The organization! People were always talking to her at home, on her husband’s island. She couldn’t bear it any more. She had to have a new life.

Sometimes Pearl thought she really did not want to have a new life at all. She wanted to be dead. Pearl felt that dead people continue an existence not unlike the one suffered previously, but duller and less eventful and precarious. She had worked out this attitude about death after much thought but it didn’t give her any comfort.

“She glanced at Sam once more. He seemed rudimentary but intense. He was a baby. He was her baby. Everyone said that he was perfect, and he was, in fact, a very nice baby.”

Pearl sipped her drink worriedly. Until recently, she had never drunk much. When she was fourteen, she’d had a drink, and in the last year she’d had maybe a dozen drinks in the whole year. When she was fourteen, she and a red-headed boy had drunk half of a fifth of gin in a broken-down bathhouse on a rainy summer day. She was wearing a cute checked bathing suit and a pullover sweater. On the wall of the bathhouse someone had carved the words NUT FLEA. After they had drunk the gin, the red-headed boy lay on top of her with all his clothes on. When she woke up, she was uncertain whether she had been introduced into sexuality or not. She walked briskly home and took a very hot bath. Nothing hurt. She kept running hot water over herself. She thought she was pregnant. When it became apparent that she was not pregnant, she feared that she was barren. She had been positive of this until recently. Now she realized she was not barren. Now she had this baby. Walker had given it to her.

She glanced at Sam once more. He seemed rudimentary but intense. He was a baby. He was her baby. Everyone said that he was perfect, and he was, in fact, a very nice baby. He had dark hair and a sweet little birthmark in the shape of a crescent moon to make him special. Shelly, after she had come back to the island with her own baby, had told Pearl that having a baby was like shitting a watermelon. Pearl would not have chosen that disgusting expression certainly, but she did feel that birthing was an extremely unnatural act. After she had passed Sam, she had gone blind for a day and a half. Her blindness hadn’t brought darkness with it. No, her blindness had just taken away all the things she had become familiar with, the room she shared with Walker, the view of the meadow, the faces and the shapes of them there, and replaced them with unpleasant delusions.

She had imagined that the child had come stillborn, that it had awakened into life only through Walker’s cry of rage. Walker was a persuasive, striking and imaginative man. Pearl could not dismiss the possibility that that he was capable of such a thing.

Pearl realized that she was no longer gazing at the baby on her hip, but at the back of the waitress’s head instead. The waitress turned slowly toward Pearl. Pearl raised her arm. The waitress stared at her for a moment and then said something to the bartender. The bartender reached for a freshly washed glass and shook the droplets of water from it. He reached for the bottle of gin and poured.

Pearl dropped the hand that ordered the drink into a gesture for smoothing her hair.

Tomorrow she would have her hair cut and try to change her appearance. Tomorrow she would forget the past and think only of the future. Yesterday was part of the encircling never. Tomorrow was Halloween. She had seen it advertised at the airport. They were going to have a party for the elderly there. Tomorrow Pearl was going to make every effort to relegate the gigantic physical world to its proper position.

The waitress arrived with the gin and tonic and placed it beside the other one, which Pearl had hardly touched. Pearl began to drink them. Her gold wedding band clicked against the glass. The ring was part of the encircling never. She tried to work it off her finger but couldn’t. The encircling never was the world that Walker’s family possessed, the interior world she was leaving, the island home.

*

Outside, the sun continued to shine maniacally. Shouldn’t it have set by now? Her hands trembled. Her hands were her ugliest feature. They were square and prematurely wrinkled. She stared at them and saw them curved around a comb, combing Walker’s hair.

Walker would find her. She suddenly knew that. And if Walker didn’t, Thomas surely would.

Thomas, her husband’s brother. A man of the world. A man of extremes, of angers, ambitions. He and Walker looked very much alike. Their coloring and weight were the same. Their thick hair, their mouths . . . The difference was, of course, that Pearl saw Walker with her heart. Once, however, Pearl had made a very embarrassing mistake. She had mistaken Thomas for Walker. It was shortly after she had come to the island, late one evening, on the landing outside their bedroom. His back was to her. He was facing the bookshelves. “Are you coming to bed soon?” she’d asked, touching his arm. Thomas turned and looked at her, his gaze flat and ironic, uncharged by love, and then had brushed past her, saying nothing. She had been grateful to him for ignoring the mistake but she had gone to her room, trembling, sweating with fear. And she had sat there, looking at objects in the room, not grasping their purpose or function anymore, very frightened, her desires and basic assumptions in doubt. Lamps, baskets, photographs, little jars of pills and scents. What were they for? What did the faces of things represent? What was it that she was supposed to recognize?

When the door to the bedroom had opened, later that night, Pearl had firmly shut her eyes.

She said, “Walker, I saw Thomas in the hallway tonight and I thought he was you.”

The figure in the room approached and stood over her. Pearl had raised her hand and touched the chest’s smooth skin.

Walker’s voice had said, “The difference between Thomas and me is that he doesn’t need women.”

Walker’s remark had not reassured Pearl as to the recognition of her desires. She didn’t want to be needed by any of them. On the island there were a dozen children, more or less, and five adults. Thomas, Walker, Miriam and Shelly were family. Lincoln was Shelly’s husband. He had been her teacher at college. From the way they told it, Shelly had kidnapped him.

Pearl supposed that she herself had been kidnapped as well. The family certainly did things in an unorthodox way. Shelly’s baby was just a few days older than Sam. They’d named him Tracker, which seemed a pretty absurd name to Pearl, although she guessed that she had named him in some wacky way after Walker. Shelly had gone off to school and come back with a husband and a baby. Lincoln was a pompous fellow who sniffed excitedly when he thought he’d made a point in conversation. Lincoln’s true predilections were uncertain, but he was nothing if not an adult. Pearl was never sure whether she should count herself among the children or the adults. The shirts or the skins. Wasn’t that a phrase?

Pearl sipped her gin.

She spent most of her time with the children. They were always seeking her out and speaking outlandishly to her. Pearl felt that they had driven her to drink. But that was all right. They were just children. She was fond of them really. What had driven her away, what had made her feel that she couldn’t bear it on the island for another day, was Thomas.

Pearl did not want her little Sam to be influenced by a man who could snap a child’s mind as though it were a twig. She blamed Thomas for what had happened to Johnny. It didn’t seem to occur to anyone else that Thomas was to blame, but it was very clear to Pearl. Johnny was a sensitive child and Thomas had pushed him too hard. Thomas thought Johnny was bright and he was determined to make him brighter. Johnny’s loves were peaches, bottle rockets and sitting on a stool in the kitchen helping his mother, Miriam, make cakes. He had been a nice little boy, wistful and impressionable but with simple needs. He couldn’t stand the weight of all that junk Thomas put into his head.

Johnny was six years old but the last time Pearl had gone into his room and looked at the bed, she hadn’t seen a little boy of six at all, but a lump of white that looked like rising dough with a face tucked in it of the hundredth day of gestation.

The last time Pearl had gone into the room she had seen ants. There, in a committed procession, had come a hundred ants. Miriam had seen them too. Miriam had said that they shouldn’t become alarmed. Had not ants come to Midas as a child and filled his mouth with grains of wheat? Had not insects visited Plato in his infancy, settling on his lips, ensuring him powerful speech? Pearl sweated. Pearl hadn’t known what to say.

Johnny had started dying, or whatever it was analogous to it, two months ago, in August. August was the month when Sam was born. August was also the month for the birthday party. The children had always celebrated their birthdays collectively. At the birthday party, Johnny had announced that he felt inhabited. He was inhabited by hundreds. There were cells in his body and all stronger than he. He couldn’t keep them ordered. He couldn’t keep them pleased. In the middle of the party Johnny had gone to his bed and hadn’t gotten up from it since. He lay with his face in the pillow, his poor little body like a graveyard in which the family dead of several generations had been buried.

He had had beautiful eyes. Before he got his notions, he had been normal enough, gorging himself on chocolate rabbits at the appropriate time of year, learning how to sail and water-color and so on, and doing everything with those beautiful and commanding eyes which were a luxurious violet color like certain depths of the sea.

In his illness, he said that he could see the blood moving though the veins of things. He said he thought he could induce the birds and the butterflies and animals of the picture books to come to life, to totter out of the books, leaving holes behind them. He said he was sure he could do this except he was afraid.

The child was overstimulated. He had been reading since the age of four. They all read at four. He worried about nuclear power and volcanoes and Beethoven’s deafness. He worried about the people who wrote to Miriam and told her the terrible things that had happened to them. Thomas encouraged him in these worries because he thought they honed the mind. Thomas told Johnny he could do anything if he just set his mind to it. Wasn’t Uri Geller able to make a closed rose unfurl just with the power of his thought? Hadn’t Christ made a fig tree wither with just the power of his annoyance? Well, now Johnny was setting his mind to something analogous to dying, and Thomas was off ruining other babies’ minds. Miriam had four-month-old twins, Ashbel and Franny, and Thomas was probably at them, even this very moment. Thomas loved babies. He would hold the twins and talk to them in French, in Latin. He would talk to them about Utrillo, about knights, about compasses. Thomas loved babies. He loved children. When they got to puberty he sent them off to boarding school and forgot about them.

In the bar, she took a breath of air, as though she were tasting freedom, and coughed slightly. She slipped her finger into Sam’s small fist. She liked her baby. She was glad they were together, alone. She was glad that neither one of them would ever have to see Thomas again. She supposed, however, that the baby might grow to miss his cousins. And his father. Pearl herself would not miss Walker much. It was true that once Pearl had seen Walker with her heart but that was no longer so. Pearl didn’t know Walker very well which was why she always set great store upon seeing him with her heart. He was very seldom on the island. She didn’t know his business. She imagined that it simply might be taking women out to lunch and then sleeping with them. She had often wished, in the months when she was pregnant, that he would have been content enough to do just that with her, instead of bringing her back to his family and marrying her.

That seemed unnecessary.

He could still have given her her baby but she would not have had to spend that lonely year on the island where she was the only one, it seemed, with any ordinary sense at all.

She was going to keep Sam calm and common. She would not let him play in a questionable manner. Everything would be bought in a store and have some sort of a guarantee. When he got sick, she was going to call a doctor.

Even when Johnny weighed only eighteen pounds, Thomas had not called a doctor. He had brought over a psychiatrist. It was like contacting a voodoo priest, Pearl thought. The psychiatrist had come over to the island in a velour jogging suit and had spoken at length about love, rage and the triumph of hateful failure. The psychiatrist had suggested that Johnny was a very willful, angry, even dangerous little boy.

Miriam had cried. They all realized that Johnny was willful. He had always gotten everything he wanted, usually just by the demands of his beautiful, insistent eyes. But it didn’t seem so bad. It didn’t bring anybody any harm. As for the idea that Johnny was angry and cruel, how could anyone, least of all Miriam, believe that? Miriam could only remember him as the child who fell asleep on her white bed after a day in the sun, smelling wonderful, tiny sea shells stuck to his bottom.

A tear popped up in Pearl’s eye as she thought of Miriam, crying. Poor Miriam. She could see her sitting by Johnny’s bed, trying to talk to him, trying to bring him back, away from the dark child’s path.

Poor Miriam. She told Pearl that she would sit in Johnny’s room and see all the confusions in poor Johnny’s head. There was a smell of sex and death and cooking, Miriam said. The slap of bodies coupling and quarreling was terrific. The racket of baroque construction. The cries and slithering, the giggles and complaints. The babies and fabulous animals. The old men. It was dark in Johnny’s room, but the people in his head were beautiful luminous clouds, delineated by flowing golden lines. The darkness, Miriam said to Pearl, held only the path. The children’s path. Dark.

Pearl put a pretzel log in her mouth. It tasted as though she were eating her napkin. Miriam made wonderful pretzels. Pearl might never get a decent pretzel again. Miriam was the best cook Pearl had ever known. She loved to bake and make. If it weren’t for her, everyone was well aware, the children would live on nothing but honeysuckle and berries. She loved cooking. She never wearied of it. The gathering, the selecting. The boning, chopping, grating. The only day she ever made a mistake in the kitchen was the day her husband, Les, had abandoned her, a week before the twins were born. She’d put sugar instead of salt in the béchamel.

*

Les had been a mess. He’d been the gardener. They’d found him when the family had vacationed once in Sea Island, Georgia, in the days before Thomas decided they shouldn’t vacation. Les was a borderline simpleton with a big handsome face and a large appetite. Miriam had never paid much attention to him. She was too busy with her sewing, cooking, shopping. How Miriam loved to shop! She approached supermarkets with joyously clenched teeth. Pearl had never done well in supermarkets. She saw Miriam as a successful conqueror penetrating a hostile country, routing out the perfect endive, the blemishless peach, the excellent cheese . . . Miriam had confided to Pearl once that she was glad Les was gone. Miriam had told Pearl he had a business bright and shiny as a carrot.

“She spent most of her time with the children. They were always seeking her out and speaking outlandishly to her. Pearl felt that they had driven her to drink.”

Pearl looked at the rings of moisture her glass had made on the barroom table. She rearranged Sam in her arms. There was a crack in the formica that had hair in it. Pearl put her cocktail napkin over it. On the napkin were animals drinking and playing poker. Pearl put her hand over the cocktail napkin.

On the wall in Johnny’s room was a picture Thomas had given him. It was a face made up from the heads and parts of animals. Arcimboldo. All the children thought it terribly witty. They envied Johnny for having it. Johnny adored Thomas for having given it to him. Pearl had never thought it very witty. She found it disgusting. A picture razored from an art book. Antlers, ears tusks, haunches, tails, teeth . . . making up the head of a man. The man’s bulbous nose a rabbit’s haunches, his hair a tangle of wildcats and horses, his eye a wolf’s open mouth. No wonder Johnny had nightmares, that wretched thing being the last he saw before he fell asleep at night. The head’s adam’s apple, a bull’s balls . . . Well, that was rather witty, Pearl thought.

Poor Johnny. Pearl could not remember what he looked like. Sometimes her memory was not good at all. Pearl would be the first to admit that her mind was like a thin pool, on the bottom of which lay huge leaves, slowly softening. Or had Thomas said that to her once? Rudely.

She remembered enough, actually. More than she cared to. She remembered the way the psychiatrist had stood in the living room, while Miriam wrung her hands, and said, “Your child dreads to become alive and real because he fears that in doing so, the risk of annihilation is immediately potentiated.”

She remembered Miriam confessing to her once that she had taken to spanking Johnny. She did it tentatively, for it felt so queer, and then stopped almost immediately and began to rock him. His pale bones floated beneath her anxious hands. She cradled him in her arms and pressed her face into his hot tangled hair. Everything felt wrong. She combed out his hair with her own hairbrush, hoping it would order his thoughts. She put a little copper bell on the table beside his bed so that he could call for her should he want her, should he ever change his mind. Pearl remembered Miriam’s hopeless voice drifting out of his room:

“Mommy’s leaving now, but in the morning I’ll make you french toast. You can put up the flag. You can go quahoging with the boys . . .”

Never again would Miriam see the tiny sea shells on Johnny’s bottom. Never again would he come back as he had been. Never, never, never. You cannot keep things the way they are. They go away. They change. There has never been an exception to this rule. No mercy has ever been shown.

Oh to bring back the days when stars spoke at the mouths of caves.

To go back to those times when one could not know, for the darkness, in what ways they had lost their former selves . . .

Pearl was beginning to feel a little nauseated. On the plane, she had won a bottle of champagne by being the passenger who, in a contest over Richmond, had come closest to guessing the combined ages of the flight crew, a number which she could not now recall. She had drunk the champagne all by herself.

The drinks here didn’t taste as good as the ones she made herself on the island. It was the sulphur in the ice cubes here or something.

A well-dressed woman with terrible breath came up to her table and bent down over Sam. She jiggled a swizzle stick at him. She thought he was wonderful.

“What all flavor is that little thing?” she asked Pearl. “Chocolate or vanilla?”

Blankly, Pearl looked at Sam and then at the woman.

“It’s just an old country expression,” the woman said, “to mean boy or girl?”

“Oh,” Pearl said. People are nice here, she thought. Sam jumped in her lap. Pearl closed her eyes, and finished her drink.

When she opened them again, the woman was gone. Across the room behind a phalanx of bottles was a mirror. Pearl did not look good in it. In the mirror, a couple appeared to be sitting beside her with a small alligator on the table between them. When Pearl turned and saw the actual table, she saw that it was so. The alligator was of the size one usually finds deceased in southern gift shops, next to the kumquat jellies. This one was dully alive. Its small feet made a gently, rustling sound, like leaves.

“You’re just too much, Earl,” the woman said.

“It’s got a dong in it big as its whole self, you know that?” Earl said. “Goddamnedest thing.”

Pearl firmly signed her check with her room number. She got up and began walking out of the bar. Her legs felt as though they were wrapped in mattresses.

The bartender interrupted her careful progress. “Ma’am,” he said. “There’s a call for you.” Unsurprised, she took the phone, and shifting Sam to her other arm, put the receiver to her ear.

There was nothing. A fading singing. Like a child’s nonsense rhymes. Or perhaps it was a problem in her inner ear.

She put the receiver back on the hook and went into the lobby. She took the elevator up to the fifth floor. She walked down a long corridor. There was a maid there, pushing a cart, collecting supper trays that guests had left outside their doors. The maid had a piece of cheese in her mouth.

Pearl fumbled a moment with the lock to her room, then pushed the door open. The room was cool and cramped. Someone had wheeled a crib into the room. There was a crib and a bed and a chair.

Walker sat in a chair, facing her.

“Hello,” he said. He got up and touched her face with his fingers.

“Darling,” he said.

__________________________________

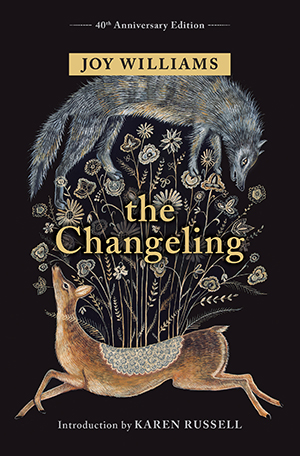

From The Changeling. Used with permission of Tin House. Copyright © 2018 by Joy Williams.