The Challenge of Confronting Hitler’s Moral Stain on Europe

Ian Kershaw on the Lasting Trauma of the Nazis’ War

The Second World War and the Holocaust defined the twentieth century as nothing else did. Hitler was the chief author of both. It would be absurd to reduce such epoch-defining momentous events to the actions of one man. It would be equally absurd to deny Hitler’s centrality to them. The motive force of his personality had been to prepare Germany to fight a second world war to expunge the national humiliation of the first, and to eradicate the ethnic minority, the Jews, whom he nonsensically saw as the cause of that disaster and of every other ill to befall his people. He had made no secret of his intentions long before he ever became a contender for political power.

In the midst of a complete crisis of state and society, the German political elite had nonetheless allowed this man to take supreme power in the country. In subsequent years every agency of political power had bound itself inextricably to him. And millions of Germans, until the steep fall in his popularity in the last war years, had cheered him and supported in different degrees the policies that led ultimately to the abyss. Germany’s descent within such a few short years from a cultured, civilized, democratic society to one ready to engage in unimaginable inhumanity was so steep that its enduring legacy was more than incomprehension: it was a trauma that gripped not just an entire nation, but an entire continent. That lasting trauma is indelibly linked to the name of Hitler.

Hitler left behind nothing constructive, such as Europe’s conqueror over a century earlier, Napoleon, had done. What economic modernization had taken place in the 1930s had been subordinated to the needs of war preparation. His own country was so totally destroyed that, under enemy occupation, it was reconstituted four years after his death in two mutually hostile states which were only reunited after the passage of four decades.

Bombed towns and cities were the obvious signs of a country’s physical devastation, a dislocated population and broken families a reflection of human loss. Hitler’s bitter legacy of ruin and suffering was felt across the whole of Europe, in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union quite especially. And nearly every country had to contend with a further legacy: collaboration with Hitler’s occupying forces.

Reminders of the moral stain still regularly occur in the twenty-first century, over seventy years after Hitler’s death.

The destruction of the Jews, the centrepiece of his ideology and at the heart of the German war that he had unleashed, was his only aim that came close to realization. Jewish communities that had enriched European culture for centuries were wiped out. Israel and the USA were the main beneficiaries of forced Jewish emigration. The foundation of the state of Israel would most likely have come about at some point without the Holocaust. But Hitler’s lethal assault on European Jewry both accelerated the development and provided moral legitimation for a development of enormous significance for post-war global history.

War and genocide have made Hitler’s legacy worldwide. Other dictators have perpetrated heinous, grotesquely terrible crimes. These have for the most part been inflicted on the population of their own countries. Hitler’s were continent-wide and, in their implication, worldwide. Far more non-Germans than Germans suffered from his rule. The drive for racial empire had subjected millions to Nazi terror. Every European country’s history, and beyond Europe especially that of the USA, is indelibly scarred by the memory of the Second World War, German occupation and family loss. Hitler is synonymous with the creed of racial hatred, hyper-nationalist aggression, the attempted domination of a master race and indescribable inhumanity.

Hitler completely destroyed the old Germany. The eastern provinces of the Reich, stretching through Poland to Russia’s borders, were lost for ever, and with them the large estates of Germany’s aristocracy that lay in these regions. Gone too was the once-mighty state of Prussia and with it the military ethos that had been such a strong strain of German political culture. Other long-standing social traditions, loyalties and structures were also broken or damaged beyond repair. Hitler had in the end accomplished a political and social revolution. But it came about through the destruction he had caused. It was the complete opposite of the one he had wanted.

Germany, and Europe more widely, have over subsequent decades recovered physically and politically from Hitler’s devastation. As the outright antithesis of the values of the Hitler era, modern Germany is the cornerstone of Europe’s constitutional, liberal, democratic value system. From the 1950s onwards West Germany (from 1990 unified Germany) has lain at the centre of the European “project” of supranational integration, the most committed driving force of what turned into the European Union. Facing up to the Nazi past has been a long and incomplete process, hampered for many years in West Germany by slow and limited judicial prosecution of Nazi crimes. Intensely troubling and difficult as it has been (and still is), it has been an essential element of the political and social transformation. Most other countries have faced their own dark pasts less courageously and more hesitantly.

The moral stain left by Hitler has, nevertheless, been harder to erase than the physical ruins he bequeathed. For almost two decades after his death it was largely suppressed, consciously or subconsciously, in West Germany by a population anxious to put the horrors of the recent past behind them, while in East Germany it was submerged beneath a Marxist-Leninist interpretation that attributed the collapse of civilization to the imperialist aggression of monopoly capitalism and emphasized the triumph of Soviet communism.

It took the grandchildren’s generation to turn a glaring spotlight on the extent of complicity in the crimes of the Nazi era and to focus public awareness on the centrality of the Holocaust—the greatest crime of all. The bitter “historians’ dispute” that occupied the West German press for weeks in 1986 revolved around the place of the Holocaust in contemporary political culture. It was a clear indication of Hitler’s long shadow over German social and political consciousness.

Neo-Nazism, of course, continues to exist in Germany and in many other countries of the world. Its hardcore support still venerates Hitler. The sense of power and domination of presumed inferiors that he embodied will probably never be totally eradicated among a small minority of society. Belief in Hitler and Nazism has tiny electoral resonance, though as an underground political force is still capable of promoting disturbing racial violence. The wider populist Right which has gained ground in recent years in many European countries, including Germany, while incorporating neo-Nazis in its base of support, has to tread extremely carefully to avoid overt association with Hitler. Any express linkage would be anathema to its political hopes. It is yet a further indication of the moral stigma that the name “Hitler” still carries, in Germany but far beyond.

Reminders of the moral stain still regularly occur in the twenty-first century, over seventy years after Hitler’s death. The return of a valuable painting, stolen from its Jewish owners during the Third Reich, might be such a reminder. So might a chance infelicitous remark by a politician. Any comment that might hint at approval of something that Hitler said or did—in fact anything other than an expression of outright, total condemnation—might spell the abrupt end of a political or media career.

Europe’s twentieth century had its positives as well as negatives. But its first half, especially, was terrible. And Hitler, more than any other individual, symbolizes the horror of that epoch. That he personally contributed in such a baleful way to the making of that history stands beyond question. He was the prime mover of the most fundamental collapse of civilization that modern history has witnessed. Other European leaders—Churchill and Stalin more than any—left indelible marks on Europe as a consequence of the victorious war they led against Hitler. But Hitler had done more than anyone else to cause that war. His colossal impact on European history during his era was second to none.

__________________________________

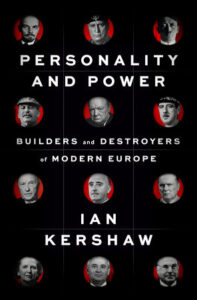

From PERSONALITY AND POWER: Builders and Destroyers of Modern Europe by Ian Kershaw, to be published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © Ian Kershaw.

Ian Kershaw

Ian Kershaw, author of To Hell and Back, The End, Fateful Choices, and Making Friends with Hitler, is a British historian of twentieth-century Germany noted for his monumental biographies of Adolf Hitler. In 2002, he received his knighthood for services to history. He is a fellow of the British Academy, the Royal Historical Society, the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, and the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung in Bonn, Germany. His newest book, Personality and Power, will be published in November, 2022.