The Brief, Joyous Life of the Sunwise Turn Bookshop

How Two Women Created a Space For Modernism to Thrive

Years later, Madge Jenison still vividly remembered the moment she decided to open the Sunwise Turn. It was a sunny day in January 1915 and she was stretched on a pillowy chaise lounge in her New York apartment, thoughts about the vital importance of books drifting through her mind “like the motive of a Mozart air.” A writer for The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Magazine and other high-profile publications, she had never before had the notion of running a business. But now, she was flooded with the urgent and undeniable realization that she must open “a new kind of book shop,” one that celebrated the “livingness” of books and spread the current of new ideas like electricity.

And she knew just who she’d open it with: Mary Mowbray-Clarke, a teacher and art critic who had studied painting with Whistler in Paris and been pivotal in mounting the 1913 Armory Show. The idea was “smoking in my mouth,” she wrote, when she rang her friend and launched an endeavor that brought together figures at the forefront of literary and artistic modernism, sparking careers that made a lasting impact on 20th-century cultural life.

Jenison wanted to “make the shop a cult…offering one a breath of experience just to buy a book there.” She found the ideal space at 2 E. 31st Street at Fifth Avenue—a Tudor-esque cottage with “booky look of a cloister.” The partners made it their own, showcasing their “ultra modern” sensibilities with orange walls, a purple sofa, blue side chairs—a “pot of paint flung in the face of the public,” Jenison said. There was a gallery with art objects on display and for sale, too. It was one of the first woman-owned book shops in America and all the initial shareholders were women.

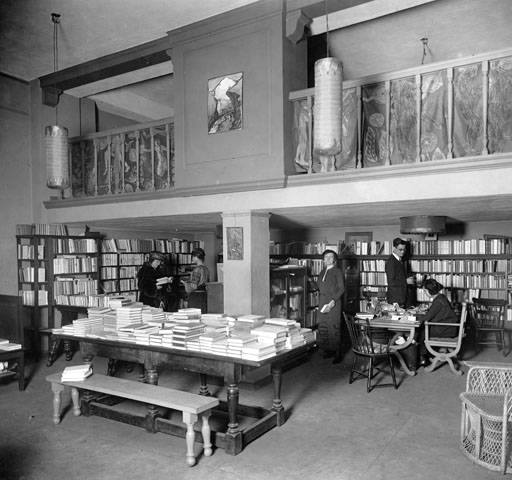

Inside the Sunwise Turn. Photo courtesy of Ohio State University, Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

Inside the Sunwise Turn. Photo courtesy of Ohio State University, Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

The partners settled on a name suggested by Mowbray-Clarke’s friend, poet Amy Murray. The Sunwise Turn expressed the idea that movement in alignment with the path of the sun and harmony with nature is fortuitous, reflective of their embrace of the ‘guild socialism’ philosophy espoused by William Morris and the general skepticism of capitalism that prevailed in their circle of friends.

When the store opened in April, 1916, Publishers Weekly described it as “visionary …quaint and bewitching” suggesting “something old-worldly, yet startlingly new.” It was “the prototype of all great-hearted bookshop experiments in a metropolis,” Mary Siegrist of The New York Times later wrote.

*

The Sunwise Turn quickly became a locus of New York’s literary and artistic scene. The shop’s first event was a reading by Theodore Dreiser. Subsequent “literary sessions” included the avant-garde, such as feminist poet Lola Ridge, up-and-comers including Robert Frost, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Wallace Stevens, and established poets such as Amy Lowell. It was the kind of place where F. Scott Fitzgerald and the pre-published Eugene O’Neill would stop by. Publishing luminary Blanche Knopf “came in with her little suitcase” talking up the company’s latest books that were “‘superlative or deserving of a larger order,’” the women’s future business partner wrote. Alfred Harcourt was on the board.

“I accepted the first rule of business: to operate without loss. Mary, however, was against capitalism itself.”

But the booksellers welcomed customers outside literary circles as well. “The Tammany politician, the jejune young anarchist just out of jail, the morose Scandinavian editor, the most sensitive of Italian diplomats, the burly English novelist,” were all the regulars. There was only one type of clientele they didn’t court. “We abominate docile people,” Mowbray-Clarke wrote in a piece about the store for Publishers Weekly in 1917.

The store was a living art project. “We worked as a Beethoven sonata should be played, with the same abandon, the same joy, the same sense of connection with the beat of one’s own heart and the rhythm of the world,” Jenison wrote. They wrapped books “in curiously brilliant packages” of colorful Japanese papers, often put together by artists who made them “so deliriously lovely that it was difficult to make up one’s mind to ever open them.” It was “a new medium,” she recounted in her memoir. “We did it because we liked doing it.”

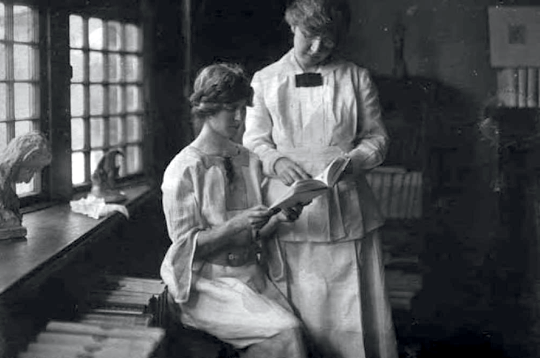

Mowbray-Clarke (seated) and Jenison in a promotional photo for the Sunwise Turn at its original location. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Mowbray-Clarke (seated) and Jenison in a promotional photo for the Sunwise Turn at its original location. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Not everyone was a fan, though. Alfred Stieglitz called the women “bloodless females who suffocate the slightest suspicion of beauty beneath torrents of gush, ” their future business partner Harold Loeb wrote in his memoir.

The partners developed a line of broadsides, featuring up-and-coming poets alongside prints or drawings by artist friends. They published small editions of books and plays, including Ananda Coomaraswamy’s “The Dance of Śiva” and a book of essays on Rodin by Rilke (who was once the sculptor’s personal secretary). They did, however, miss out on a significant opportunity. To Sylvia Beach, Mowbray-Clarke wrote, “I think we know you and you know us. I hear you have a nice little book-shop in Paris… I enclose an order for copies of ‘Ulysses.’ I hope you will allow us a discount on the books. We thought of publishing it here but didn’t have the money. …Hoping for your best success.”

*

Mowbray-Clarke believed there were two types of booksellers: the order-fillers responding to public demand and those who tried to shape it. She and Jenison were avowedly the latter—curators, educators and tastemakers—evangelical about igniting minds with the power of ideas. “Plato had to be in our shop with Lao-Tzu and the Mahabharata and Whitman and St. Francis,” Mowbray-Clarke wrote. The partners prided themselves on introducing international authors to Americans and took a risk on a big order of the little-known British author Virginia Woolf.

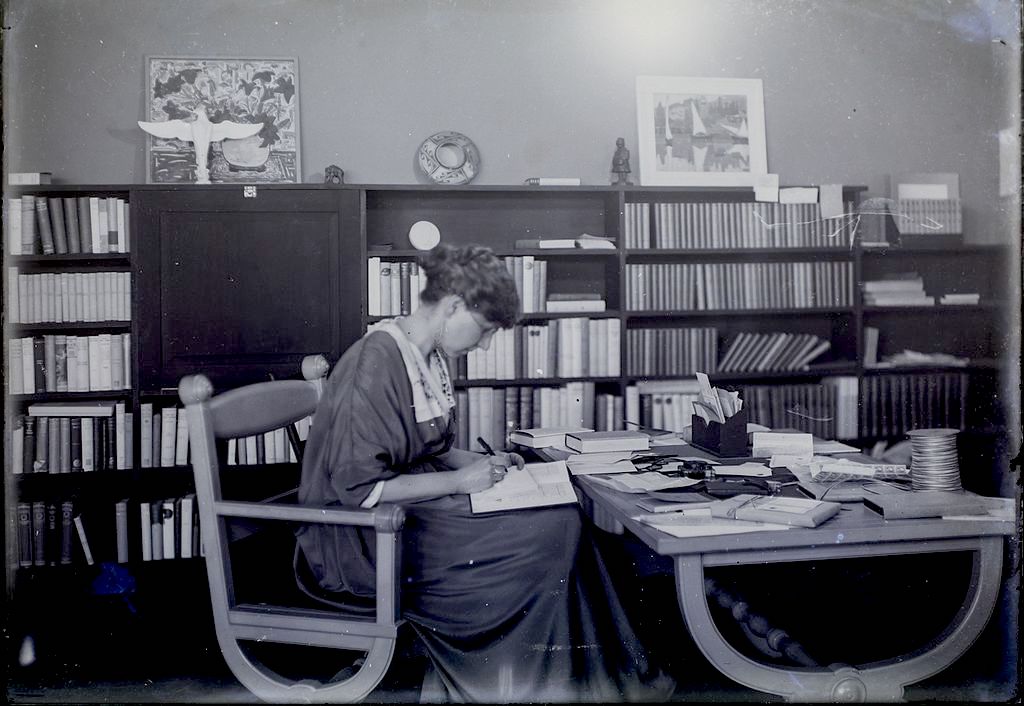

Madge Jenison at her desk. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Madge Jenison at her desk. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Seeking advice from a bookseller, they believed, should be on par with consulting a doctor or lawyer. They created libraries, tailored collections, and reading lists for clients. “A man or woman will ask us for such a list. Hours will be spend in thought …a whole Saturday Evening Post review will be written especially for him or her,” Mowbray-Clarke wrote. W.E.B Du Bois requested a list for his daughter Yolande, eventually ordering Edgar Lee Masters’ “Spoon River Anthology,” and “Green Mansions,” by W.H. Hudson, among others.

In 1919, the store lost its lease and moved uptown to the Yale Club building at 51 East 44th Street, across from Grand Central Station. The women went into business with Loeb, the writer and editor upon whom Hemingway based “The Sun Also Rises” protagonist Robert Cohen. Along with capital, Loeb, brought in his bored young cousin Peggy Guggenheim as a volunteer. She would swan into the shop “highly perfumed in earrings with little pearls and a magnificent coat” and ”heels lined in pink chiffon,” Jenison wrote, but was so bad at bookselling that she was only allowed on the floor Thursdays at noon and spent the rest of her time sweeping and running to the store for lightbulbs. She later wrote that Mowbray-Clarke was “like a goddess to me” and it was here she developed her lifelong passion for art collecting.

*

Neither woman’s approach to bookselling was particularly conductive to positive cash flow.

Jenison “sold books like a tornado,” according to Loeb, “swooping around, picking up a volume, here, dropping one there, scribbling the wrong title… leaving a trail of debris and confusion behind her.” For him, he wrote, “the ‘profit system’ existed whether I liked it or not… I accepted the first rule of business: to operate without loss. Mary, however, was against capitalism itself.” His partners were more intent on getting their ideas across than on selling books, he added.

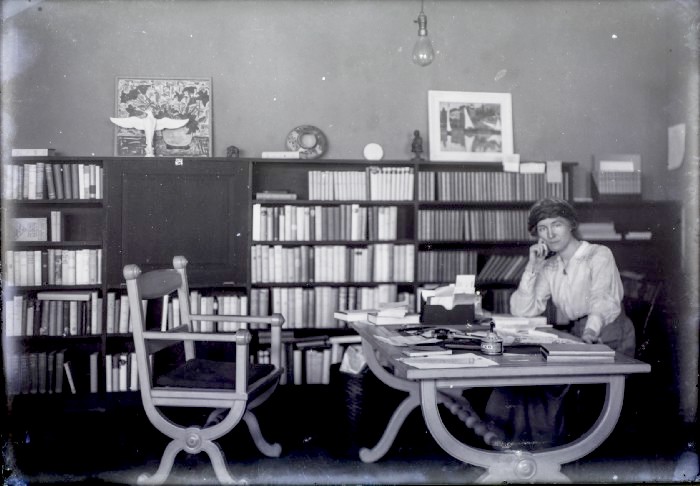

Mary Mowbray-Clarke at her desk at the Sunwise Turn. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Mary Mowbray-Clarke at her desk at the Sunwise Turn. Photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

When they’d opened the store in 1916, the women figured they’d need to sell $20,000 of books each year, or 60 books a day. The hoped-for results never materialized. “How do people appear so intelligent and read so few books? … does not everyone who does read a good book at once feel enlarged and made more of a civilized creature?” Mowbray-Clarke opined in one of the shop’s corporate reports.

In 1920, Jenison left the store. Although she didn’t publicly share the reason, it’s possible that the desire to focus on her own writing prevailed. Loeb and his wife left later that year, moving to Rome to start the famed Broom literary magazine, leaving Mowbray-Clarke the sole proprietor.

“I advise every woman in the world to sell books.”

By then, she’d become disillusioned by public taste and book-buying habits. “Fancy, though, serving a public ninety-nine per cent of whom were afraid to buy on our heartiest recommendation …. Yet they will swallow volume after volume of Michael Arlen,” she wrote in the shop’s annual report to its board of directors for 1923-24. (Arlen was a popular author of psychological thrillers at the time.) Worse still, they’d buy those cheap books at Macy’s or the corner pharmacy instead of an independent bookstore like hers. “Other forms of amusement” including automobiles and motion pictures diminished interest in books, according to a Publishers Weekly report from the era. Before the store even opened, Norman Baker, co-founder of Baker & Taylor, had warned Jenison, that “You cannot possibly make bookselling pay. The only way any bookshop survives is through its stationary.” Booksellers had to contend with an early form of showrooming as well. Mowbray-Clarke described creating a list of 75 books for a client who ordered two, then told her he’d get the rest from Brentano’s, a chain store.

In March of 1927, Mowbray-Clarke finally pulled the plug. Doubleday Page & Co. took over the lease and stock, absorbing it as the ninth of their American chain stores. Mowbray-Clarke took up landscape design and continued to be a major figure in the Rockland County arts community for decades. According to Justin Duerr, who is currently writing a biography on Mowbray-Clarke, she and Jenison remained lifelong friends.

In 1923, Jenison published her memoir about her time in the book shop, The Sunwise Turn—A Human Comedy of Bookselling. In spite of everything, she had no regrets. “When earnest girls asked us if they should open book shops, we always advised them to do it,” she wrote. “Find the capital if they did not have it. Take the shivering plunge, meet the crises and take the returns… if there were any. I advise every woman in the world to sell books.”

Main photo courtesy of Justin Duerr.

Joanne O'Sullivan

Joanne O'Sullivan is a freelance writer in Asheville, North Carolina. She's currently working on a novel about the women of The Sunwise Turn. You can find more of her work at www.joanneosullivan.com.