Of Asher Rubin and his gloomy thoughts

Asher Rubin walks out of the starosta’s home and heads toward the market square. With evening, the sky has cleared, and now a million stars are shining, but their light is cold and brings down a frost upon the earth, upon Rohatyn. The first of this autumn. Rubin pulls his black wool coat tighter around him; tall and thin, he looks like a vertical line. The town is quiet and cold. Candlelight glimmers weakly from some windows, but, barely visible, it looks more like a mirage, and could easily be conflated with the trail left by the sun on your iris from a sunnier day, and Rubin’s memory goes back, lingering on objects it’s encountered before. He is interested in what we see when our eyes are closed, and where that thing we see comes from. Whether from impurities on the eyeball, or because the eye is configured more like the lanterna magica he saw in Italy.

The idea that everything he sees now—the darkness punctuated by the sharp points of the stars above Rohatyn, the outlines of homes, small, tilted, the lump of the castle, and not too far away the sharply pointed church tower, like apparitions, the well-pole shooting askew into the sky, as if in protest, and maybe even the rumble of the water from somewhere farther down, and the very light scraping of the leaves the frost has taken—the idea that all of that arises out of his own mind is both terrifying and alluring in equal measure. What if we’re imagining all of it? What if each of us sees everything differently? Does everyone see the color green the same? Or is “green” maybe just a name we use as if it were a paint to coat completely distinct experiences in order to communicate, when in reality every one of us is viewing something different? Is there not some way this can be verified? And what would happen if we were to really open our eyes? If we were to see by some miracle the reality that surrounds us? What might that be like?

Asher has these kinds of thoughts fairly frequently, and then he starts to be afraid.

Dogs begin to bark, and men’s voices rise, and shouts break out—that must be coming from the inn on the market square. He goes in among the Jewish homes, passing to the right of the big, dark mass that is the synagogue; from down where the river is comes the smell of water. The market square separates two groups of Jews who are in conflict with one another, mutually hostile.

Who are they waiting for? he thinks. Who is it that’s supposed to come and save the world?

What do the two factions hope for? There are those in Rohatyn who are faithful to the Talmud, squeezed into just a few homes that make up something like a fortress under siege, and there are the heretics, the renegades, toward whom, deep down, Asher feels an even greater aversion, for they are primitive, superstitious, with their muddy, mystical prattle, clanging their amulets, smiling their secret cunning smiles, like Old Shorr. These people believe in a miserable Messiah, the kind who’s fallen as low as anyone can go, for it is only from the lowest place, they say, that you can rise to the highest. They believe in a tatterdemalion Messiah who has already arrived. The world has been saved already, although you might not see it at first glance, but those in the know cite Isaiah. They skip the Shabbat, they commit adultery—sins incomprehensible to some, to others so banal there is no sense in giving them much thought. Their houses on the upper part of the market square stand so close together it looks like their facades have been joined, creating one row, strong and solid like a military cordon.

That’s where Asher is going now.

This Rohatyn rabbi, a greedy despot eternally agonizing over petty absurdities, often summons him, too, to the other side of the square. He does not particularly esteem Asher Rubin, who rarely goes to synagogue and doesn’t dress in the Jewish or the Christian fashion, but rather in between, in black, in a modest frock coat and an old Italian hat by which the townspeople recognize him. In the rabbi’s house, there is a sick young boy for whom Asher can do nothing. In truth, he wishes him death, so that his undeserved young suffering might end soon. It is only on account of this boy with the twisted legs that he feels any sympathy for the rabbi; otherwise he considers him merely a vain and mean-spirited lout.

He is certain the rabbi would like for the Messiah to be a king on a white horse, riding into Jerusalem wearing gold armor, perhaps with an army, too, with warriors who would seize power alongside him and bring about the final order of the world. That he’d want him to be like some famous general. He would strip the masters of this world of their power, and they would give him every nation without a fight, kings would pay him tributes, and at the River Sambation he would find the ten lost tribes of Israel. The Temple in Jerusalem would be released fully formed from heaven, and that same day, those who had been buried in the Land of Israel would rise from the dead. Asher smiles to himself when he remembers that those who died outside the Land of Israel would not be resurrected for another four hundred years. He believed that as a child, even though it struck him as cruelly unfair.

Both sides accuse each other of the worst sins, both engage in a war of intelligence. Each is as pathetic as the other, thinks Asher. Asher Rubin is a misanthrope, after all—it’s strange he became a doctor. People always irritate and disappoint him.

As for sins, well, he knows more about them than anyone. Sins get written on the human body like on parchment. The parchment differs little from person to person. Their sins are surprisingly similar, too.

__________________________________

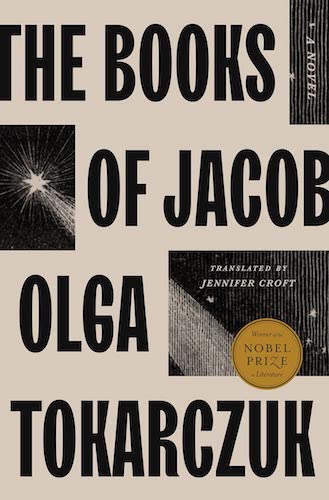

Excerpted from The Books of Jacob by Olga Tokarczuk. Copyright © 2022 by Olga Tokarczuk. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.