The Booker Revisited: On Love's Many Manifestations in A Green Equinox

Lucy Scholes Sheds Light On Elizabeth Mavor's Overlooked Modern Classic

Some of the more intriguing volumes on the Booker Library’s shelves are the ones that have, over the years, fallen out of print. One of these is Elizabeth Mavor’s A Green Equinox. Shortlisted in 1973, today it’s a conspicuous unknown compared to the novels it was up against: Beryl Bainbridge’s The Dressmaker, Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince, and that year’s winner, J. G. Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Hopefully though, Mavor’s novel is about to reach new readers. Fifty years after it was first published, A Green Equinox is being rereleased this September, by McNally Editions in the US—where, full disclosure, I’m the editor who acquired it—and as a Virago Modern Classic in the UK.

Given how neglected Mavor’s reputation is today, it might come as a surprise to learn that when she made the Booker shortlist, she was 46 years old, and the author of three previous novels and two biographies; all of which had been very well received. The first, Summer in the Greenhouse (1959), appeared under Hutchinson’s “New Authors” imprint, which had been announced two years earlier with the aim of drawing particular attention to exciting up-and-coming talent (and who published the debuts of five future Booker nominees, including, coincidentally, both Bainbridge and Farrell). “When a novel as good as this is written, and a new writer makes such an entrance, everyone can congratulate himself, a real discovery has been made,” agreed the Glasgow Herald in their review of Mavor’s debut, while the TLS compared her writing to that of both Elizabeth Bowen and Elizabeth Taylor. I think her work has more in common with that of Iris Murdoch, A Green Equinox in particular. The two women were much more than just competitors for the Booker; Murdoch—who was only eight years her student’s senior—was one of Mavor’s tutors at St Anne’s College, Oxford, and they remained friends long after Mavor matriculated.

A Green Equinox’s subject is love and its multifarious manifestations: carnal, romantic, or cerebral.

Throughout the 1960s, Mavor’s subsequent novels—The Temple of Flora (1961) and The Redoubt (1967), which was reprinted last year—continued to win her praise. She also established herself as a perceptive and diverting biographer. The Observer commended her first foray in this genre, The Virgin Mistress: A Study in Survival (1964)—which documents the life of Elizabeth Pierrepont, Duchess of Kingston (1721-1788), an English courtesan famous for her adventuress lifestyle—as “high-spirited and entertaining.” The Telegraph, meanwhile, declared it a “delightful […] human, well-documented book about one of the most extraordinary Englishwomen of the eighteenth century.”

Mavor’s second biography, The Ladies of Llangollen: A Study in Romantic Friendship (1971), tells the story of the cross-dressing aristocratic companions Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby. In 1778, these Irish gentlewomen scandalized their families by eloping to Wales, where they henceforth lived together on their own terms. Not only is it her best known work, but it makes an elucidating companion piece to A Green Equinox. Although the Ladies lived together as in a marriage, Mavor isn’t convinced that their relationship was a sexual one. She argues that the nuances of what she terms their “romantic friendship”—”tenderness, loyalty, sensibility, shared beds, shared tastes, coquetry, even passion;” in essence, “much that we would now associate solely with a sexual attachment”—can’t be neatly mapped onto a matrix of modern alliances: “Depending as they did upon time and leisure, they were aristocratic, they were idealistic, blissfully free, allowing for a dimension of sympathy between women that would not now be possible outside an avowedly lesbian connection.”

One certainly doesn’t have to have read The Ladies of Llangollen to appreciate or enjoy A Green Equinox, but it does give us a way to read the singular romantic escapades of Mavor’s fictional heroine, the eccentrically though aptly named Hero Kinoull. The novel is a Bildungsroman of a sort, even if Hero—an antiquarian bookseller and binder who lives in the English village of Beaudesert—isn’t in the first flush of youth. Between the spring and autumn equinoxes of a single year, she undergoes a journey of emotional, spiritual and romantic transformation, as she attaches herself in turn to three distinctive love objects; each of whom represents a different state of being, and teaches her a different way of being in the world.

The novel opens in March, with Hero already ensconced in an affair with Hugh Shafto, the curator of a large collection of rococo art. United by their shared passion for what Hero grandiloquently describes as “the beautiful ancient,” and brought together by “books, beautiful but so dangerous books,” the only fly in the ointment is that Hugh is married. Though the difficulty this causes isn’t that which we might expect.

Having thus done her best to avoid encounters with her lover’s spouse—the glorious, do-gooding Belle, who always has a cause to champion: “Race Relations, Pollution, H-bombs, perhaps even Noise Abatement […] Unmarried Mothers? Dangerous toys? Abortion? Pink-footed geese?”—when the women’s paths do finally cross, Hero finds herself hopelessly drawn to this glowing “Valkyrie”-come-“Earth Mother.” Belle yanks Hero out of the “refuge” she takes in all things ancient, and shows her what it means to have one’s sights set firmly on the future. For Belle, the only despair lies in inaction; she zealously believes in the possibility and promise of change. “I think something can always be done,” she tells her new friend, inveigling Hero into joining a local protest to save an ancient tree that the council want to bulldoze.

But having seamlessly transferred her affections from husband to wife—much to Hugh’s initial alarm, and then his slowly unfurling chagrin—in an even more unforeseen move, Hero subsequently meets and falls in love with Hugh’s mother. The formidable Kate Shafto, who wishes she’d been born a God, lives on the edge of a disused gravel pit that’s she’s turned into an inland sea, upon which she sails ornate, homemade miniature boats. And it’s here, in the adoring companionship that she forges with Kate as the autumn equinox arrives, that Hero finally learns both the pleasures and pains that living fully in the present entails: “It was an affection hard to describe, for it had about it the curious touch of passion once shared, though at a very long time back in the past, in the blood almost: and of a passion, or perhaps even an ecstasy, which was due to be shared at some great distance in the future. Yet these perceptions of past and future time seemed to be contained completely in the quiet almost humdrum present in which we lived together.”

There’s also an impressive array of incident and action along the way, including—in no order of significance or chronology—a car crash, a fire, a drowning, a bout of typhoid, and a suicide. Above all, though, A Green Equinox’s subject is love and its multifarious manifestations: carnal, romantic, or cerebral. Love that burns bright in physical longing, and that which glows warmly in the soft comfort of companionship. This is a book that wallows in embodied, visceral experience. It is about life and death and the inevitable passage of time. Emotions are made manifest on the page; bodies pulse with desire, but also with decay. Love can multiply dangerously like insidious incubating typhi bacilli, but it can also blossom with the lush verdancy of a “beautiful Xanadu garden,” turning Hero’s body into “a landscape from Paradise,” one “whose sharp springs, welling over into pools, warm and green as at Clitumnus, spill again into water-meadows, which engulf to the belly the fat white oxen browsing there in the high grass, and then they run away in bright welling streams to the deep river which, inexorably flowing, causes my legs, inert marble as they have become, to sag apart in order to admit of its enormous dark sweetness.”

This clotted abundance is typical of Mavor’s prose. She is an unapologetic maximalist, who indulges in hyperbole, metaphor and poetry. But her flights of linguistic fancy are always tempered by a return to reality. One minute she’s invoking Roman mythology, the next she’s comparing somebody to a bathroom fixture—”Belle’s nature was smooth and antiseptic, a flat white statement, as alien and inarguable with as a toilet pedestal”—and there’s a beauty in each. Her sensuality reminds me of the heady pleasures of the flesh that Brigid Brophy invokes in The Snow Ball (1964), a novel that Brophy’s lover Iris Murdoch described as “sheer artistic insolence.” I wonder if Murdoch thought the same of A Green Equinox? She surely read it.

Emotions are made manifest on the page; bodies pulse with desire, but also with decay.

“O Holy Britomart!” Hero’s expostulation during her first encounter with Belle, seems to echo Judith’s famous utterance, “Glorious pagan that I adore!” in Rosamond Lehmann’s Dusty Answer (1927), uttered as the novel’s young heroine feasts her eyes on her beloved: Jennifer, a fellow student at Cambridge, with whom Judith’s forged a passionate—possibly sexual, but definitely romantic—intimacy. Belle’s assertion “that what we nowadays associate with a purely sexual relationship once also played a part in relationships that weren’t specifically sexual,” reiterates Mavor’s thesis of the “romantic friendship” that she proposes in The Ladies of Llangollen—one that’s “more liberal and inclusive and better suited to the diffuse feminine nature.” And while there’s an unarguable and very strong sexual dimension to Hero’s attraction to Belle—”I am a parhelion, I am a shell-thin alabaster sphere filled with fire and myrrh,” she baroquely opines as her body quivers with desire—we shouldn’t dismiss the fact that the first awakening that she experiences in Belle’s company isn’t sexual, it’s emotional: a realization that she’s been “starved” of female companionship since her school days. This easy comfort of a natural shared sensibility—what Mavor describes as that “sympathy between women” in The Ladies of Llangollen—that Hero feels in Belle’s company is nothing short of revelatory.

So too Hero’s relationship with Kate leads to its own similarly momentous Damascene moment; the quiet contentment of their life together—in which they potter about the older woman’s “small kingdom” planting bulbs and seeds, working side-by-side in the evenings, Hero on her book-binding and Kate on her model ship-building—introducing her to a whole new definition of love. “I have never known anything quite like this before, outside a lover’s bed,” Hero marvels. “I mean the expanding of the word, so that it can become an experience. Or conversely, the imploding of the experience so that it becomes a word.” As the Observer’s reviewer suggested on the novel’s original release, this is “a book whose unusual infatuations are well worth lingering over and puzzling out.”

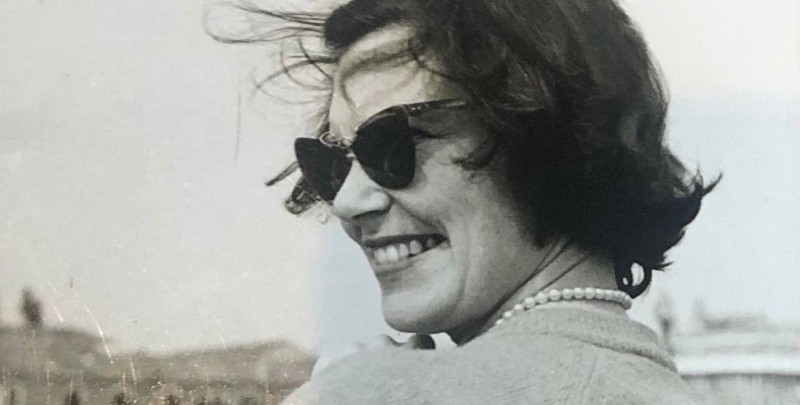

And what of Mavor herself, you might ask? Well, she was born in Glasgow, but spent most of her life in Oxfordshire. She was married to the illustrator and cartoonist Haro Hodson for 60 years—they wed in 1953, only three years after she graduated from Oxford, had two sons, and remained together until her death, at the age of 85, in 2013. But in a similar way, perhaps, to that in which both Murdoch and Brophy’s marriages to their respective male partners encompassed their relationship with one another, so too Mavor’s marriage to Hodson allowed her space for a romantic friendship of her own, with the sculptor Faith Lucy Tilly Tolkien.

Although not the last novel she wrote, A Green Equinox did mark the end of a particular stage in Mavor’s writing; thereafter she was drawn back to the stories of real-life “extraordinary women.” Her final novel, The White Solitaire (1988), was a fictionalization of the story of the famous eighteenth-century sailor-for-hire-turned-pirate Mary Read, who lived much of her short life disguised as a man, and in the early 1990s, Mavor—who was a dedicated life-long diarist herself—edited and compiled for publication the journals of a handful of other trailblazing eighteenth-century women: Katherine Wilmot, an adventurous young Irishwoman who documented her travels in France and Russia; the American actress Fanny Kemble; and the travel writer and naval captain’s wife Maria Graham. As Janet Adam Smith wrote in her LRB review of Wilmot’s diaries, “Elizabeth Mavor relishes spirited, unorthodox women, free with their tongues and ready to snap their fingers at convention.” In this, as in her portrayal of the complexities of what we might today best describe as queer love, Mavor’s work seems ripe for revival and reappraisal.

_____________________________

‘TBR: The Booker Revisited’, is an editorial partnership between The Booker Prize Foundation and Lit Hub.

Visit the Booker Prizes’ website for more features, interviews and reading recommendations covering the hundreds of books that have been nominated for its annual awards. Sign up for the Booker Prizes Substack here.

Lucy Scholes is a critic based in London and Senior Editor at McNally Editions.

Lucy Scholes

Lucy Scholes is a senior editor at McNally Editions, and writes for The Independent, The Times Literary Supplement, The Observer, BBC, The Guardian, and is a columnist for The Paris Review.