The Book Research No One Would Want: Time in the ICU

Paul Griner on What Time in the Hospital Can Reveal About Character

On my 52nd birthday, the phone rang at 2 am. It was the New York State Police, telling me my daughter had been in a terrible car accident. “I’m not a doctor,” the trooper said. “But I think she might make it.”

Before I could reply, my phone buzzed; caller ID said it was a Westchester hospital. The ICU nurse asked if it was my birthday. “Your daughter kept saying she needed to call you.”

That made me feel better. Surely if she was talking about my birthday, she was okay. But as the nurse listed my daughter’s injuries, I began to lose hope: a broken eye socket, nose, jaw, collarbone, humerus, broken ribs and vertebrae, 47 fractures in all, plus damaged organs.

I asked, “Is she going to die?”

“Oh no,” the nurse said. “She’ll make it.”

By 7 am I was on a plane, and by 11 I was at her bedside. Her hair was tangled with dirt and leaves, dried blood still covered her swollen face, and where she wasn’t bloody she was beginning to bruise. She’d already had one surgery; she would have several more. I wanted to touch her, but I wasn’t sure where on her body wouldn’t hurt, so I just stood and watched, making sure she was breathing. Her foot, the nurse finally told me, so that’s what I touched. I was so grateful to feel her warmth.

*

We transferred her to Mt. Sinai, a 40-minute ambulance drive. My wife rode with her, while I turned in a rental car and paid our motel bill. On my way to the city, I got texts from my wife, each with greater urgency, asking if I was close. But when I finally got to her room, my daughter said hi. Then she said her benbow hurt.

“Your elbow?”

“That’s what I said. My benbow.” She started making odd sounds, her eyes rolled back, and she stopped breathing. Alarms went off and doctors and nurses rushed into the room and revived her, rolling her bed as they did, my wife and I trailing along behind, terrified.

“She has a brain injury,” one nurse told us. “I worked in the neuro-ICU for years. You’ll probably get her back, but it’ll be a long process.”

For the next month, she was on the neuro-ICU ward. Fifteen or twenty beds arcing around the room, blue sliding curtains between them, and in every one a bad case: strokes, car accidents, victims of beatings, unsuccessful suicides. All with neurological trauma, all of whom were constantly monitored and frequently tended, many of whom would die.

The phone rang at 2 am. It was the New York State Police, telling me my daughter had been in a terrible car accident.

She stopped breathing once more, and for a while afterward she got so loud, screaming and cursing, that they cleared out all other visitors except my wife and me. Her bay was too narrow for both of us to be with her, so we took turns sitting beside her or in the waiting area just outside. At times, even there, you could hear my daughter yelling.

The man in the bed next to her was 42, Dominican American; he’d had a stroke. His family, huge and close, rotated in and out of the waiting room hour by hour. Once, when my daughter was screaming, his father touched my knee and said, “It breaks my heart to hear that. So young.”

They brought stacked and overflowing Tupperware containers of home-cooked rice and beans, plantains, chicken. His wife offered me some, and at first I said no, but once I took a plateful I couldn’t get enough; it must have looked as though I hadn’t eaten in months. Later, I went out and bought a huge box of donuts for the whole family.

Later still, he died. All of his family was allowed in for the last moments. So much sobbing, so much grief. I tried not to look at his little girl. My daughter was breathing on her own then. Two weeks later she left the ICU; a week after that she was home. Eventually, she made a full recovery.

*

Years before the accident, I’d woken from a dream with the names Otto and Liam. I knew that Otto was the father, a freelance artist, Liam his young son, wounded in a school shooting, but, for a long time, that was all I knew about these two imaginary characters. Now and then, I’d open a file I’d started about them on my computer, which at first contained only their names and these bare facts, stare at it, and go back to other things I was writing; two novels and a collection of stories.

A couple of years after the accident, I again opened the file on Otto and Liam. At that point, I knew that Liam would be on the neuro-ICU ward after the shooting, and I knew a lot of what would befall him and his parents. The terrors of intubation; the confusion over obscure medical terms that professionals dropped into every conversation; the casual way a doctor would say she wondered if Liam’s brain had actually been destroyed by the shooting (look up “brain shearing” if you want to be scared) despite what CT scans and MRIs showed; the way another well-meaning doctor would take Otto aside to show him a picture of Liam’s brain with a sea of blood on one side, and the corpus callosum shifted five degrees to the left by the force of the shooting and subsequent fall down a long flight of stairs.

I thought about how lucky we’d been to oversee my daughter’s care, how much it mattered, and how the ramifications of COVID are going to be felt in ways we haven’t yet begun to imagine.

I also knew the details of the neuro-ICU ward (the swish of a curtain being pulled between beds meant an invasive medical procedure or last rights), its moments of peculiar levity—as when Otto was asked to be a witness for a will, the entire ceremony conducted in Ukrainian—and the unique rhythms of its waiting room, where Otto and his wife May would spend hours day after day, week after week, month after month, on their visits to their wounded son. And I knew the other visitors who would be there with them, also waiting, hoping for good news about their spouses, parents, children, siblings or friends.

All of that went into the book.

*

As publication drew closer, I kept changing the dates in the novel, wanting it to be current. The story moves forward on two parallel tracks: one begins at the moment of the shooting, when Otto and May are at the hospital, overseeing the care of their wounded son, and the other comes three years later, when Otto is being hounded by hoaxers who want him to admit the shooting never happened. Since the book was scheduled to be released in 2021, I started the timeline of the “current” events in 2020, until one friend pointed out that I didn’t mention the COVID pandemic in any of those numerous pages, so I had to go back and change all the dates again, this time to before the pandemic. But doing so made me realize other things: I wouldn’t have written the same novel if my daughter’s accident had happened during the pandemic, and she might not have survived.

During her hospitalization, my daughter suffered from post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), a catchall for the physical and mental impairments that commonly occur during an ICU stay. In the book, Liam does too. PICS can negatively affect long-term prognosis, and prevention of PICS requires many things; two of the most important are family intervention and follow up from the time of ICU admission to discharge. But during most hospitalizations from COVID, families weren’t allowed into the ICU; it was too risky for the patients, for healthcare workers, and for them. And, given how stressed many hospitals were, it’s reasonable to assume that follow-up on ICU admissions suffered. Both things matter.

At least one study has shown that certain patients who survive two years after their discharge from the ICU can have up to an 80 percent readmission rate. One study suggests that for those who survive the ICU with COVID, the percentage will be even higher, especially for those suffering from PICS. For some COVID ICU patients, the only contact they had with family members after admission came at the end of life, via tablets.

I thought about that a lot during my final revisions of the book—how lucky we’d been to oversee my daughter’s care, how much it mattered, and how the ramifications of COVID are going to be felt in ways we haven’t yet begun to imagine.

*

But of course, imagination is central to any novel, no matter how much it’s based on lived experience. I knew as I wrote Otto and Liam I’d have to mix the lived with the imagined, because Otto’s situation wasn’t mine. Shootings cause different brain injuries than car accidents, so I had to research that. And I also knew that Otto would be confronted with the terrible new reality of hoaxers who claim school shootings are false-flag events staged by the government.

You learn a lot about writing while you live, though at the time, you often don’t know it. The things that mark you will come out in your work, whether you plan on it or not; they’re like horses fleeing a burning barn, and you have to be ready to ride them. You also have to be ready to examine them, and yourself, once you have a draft. Denis Johnson has said he put off writing Jesus’ Son for a long time because he didn’t want people to realize what kind of person he’d been when he was an active addict. I hadn’t admitted some of the dark thoughts I’d had while sitting in that neuro-ICU waiting room to anyone, but I knew those were part of Otto’s experience—that he was ashamed of them, yet didn’t regret them. I knew, too, that they made him more complex, more fully human, and that they therefore had to be in the book.

Now, a lot of those thoughts are in the book, and so my secret is out. But it’s okay. In the end, we have to matter a lot less than our work, if we want our work to matter.

__________________________________

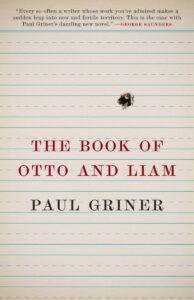

The Book of Otto and Liam is available from Sarabande. Copyright © Paul Griner.

Paul Griner

Paul Griner is the author of the recently published novel The Book of Otto and Liam. Earlier work includes the novels Collectors, The German Woman, and Second Life, and the story collections Follow Me (a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers pick) and Hurry Please, I Want to Know (winner of the 2016 Kentucky Literary Award). His work has been published in Playboy, Ploughshares, One Story, Zoetrope, Narrative, Tin House, and Bomb. He teaches writing and literature at the University of Louisville.