The Best Dog Poems Reveal the Good and the Mischievous in Our Canine Friends

Duncan Wu Goes Deep on a Blessed Genre

Sometimes I find myself reciting poetry to Topsy, the smooth fox terrier from Texas who my wife rescued seven years ago. As with everything else I say to Topsy, she understands every word, and indicates her approval of the poem by tapping me with her paw; if she doesn’t like it, she walks away. I’m sure, if she were capable of speech, she would make learned observations—“Bad use of dactylic hexameter,” that kind of thing.

Poetry is in most cases an intimate thing, something that springs from deep within the psyche, and if it gets so far as to find words to incarnate the thought, that too is intimate, carried out in that unknown place where intellect and emotion come together and find articulation.

That poets should want to write about dogs seems to me the most natural thing in the world, because—as all dog-owners will know—dogs are a stimulus for our most honest, unedited utterance. Their function is to invite a degree of candor I would not offer even to my wife or my closest friend, and to respond in what seems to them the most appropriate way. Topsy has a multitude of responses to the various things I say to her during the day, from a paw-stroke to a bark, depending on her mood and the intensity of her feeling.

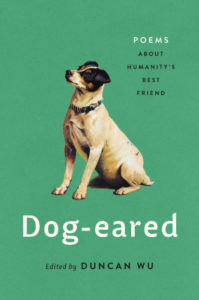

In Dog-eared, my anthology of poems about dogs, it is impossible to avoid the connection between dogs and the deep, sometimes profound, honesty of which human beings are capable.

Why poetry? There is much fiction and nonfiction about dogs, but poetry, being more compressed, can deliver more effectively that emotional jolt I’m looking for. I want to read something about a dog and be moved to laugh or cry, and poetry is the medium through which emotion works most powerfully.

Some dog poems too readily lose sight of the bestiality of their subject.

If you doubt that, take a look at William Stafford’s “How It Began” or Toi Derricotte’s “The Good Old Dog.” I want the poet to hurl me against the window of the imagination and compel me to stare in horror or disbelief or wonder at the unfolding drama on the other side. I want to forget myself and be immersed in someone else’s world.

This isn’t the first book of its kind; anthologists have been compiling canine collections for decades. One approach is to gather together heartwarming, escapist verse that shows what incorrigible scoundrels dogs can be, but that’s not the idea behind Dog-eared. Readers in the 21st century want something firmer-edged, with a foothold in the world of tough breaks and hard knocks—poetry from a world recognizably our own.

Some dog poems too readily lose sight of the bestiality of their subject. The animal they describe doesn’t seem like a creature that could roll in excrement; it is instead an ersatz dog—not real, but a hurried squiggle with doggy features—constructed and styled to satisfy the appetite for cuteness.

Such poems are problematic because they flatter dogs and flatter us. And they have an inbuilt tendency to veer rapidly into the realm of kitsch. We should not forget that our ancestors, as well as people today, have shown cruelty toward dogs to the point of terrible violence. Bear-baiting was practiced in England up to the 19th century. Bears suffered the most, but many dogs were also killed or injured.

Only in 1835 did Parliament pass a law outlawing bear-baiting, though baits continued in various parts of Britain until 1842. The prohibition didn’t stop people from engaging in other acts of cruelty, like tying fireworks to dogs’ tails for “fun,” and in fact gave impetus to the demand for dogfighting, which continues to this day in various countries.

You can’t build an awareness of that into your work if your dogs are carved out of polystyrene and live in Arcadia. That most intelligent of poets (and now one of the most shamefully neglected), Howard Nemerov, reflects on his affinities with the dog he walks each day in “Walking the Dog”. He and his mutt are, he says, two universes “connected by love and a leash and nothing else.”

He refines that observation by saying they are also connected by “our interest in shit”—one of the most honest comments he could have made because it incriminates not just the dog, but us too. Nemerov is nothing if not honest—and the catalyst of that honesty, however uncomfortable it might make us—is his dog.

Kipling loved dogs as much as Nemerov, and he wrote two memorable poems about the pain of mourning them, “The Power of the Dog” and “Four-Feet.”

I have done mostly what most men do,

And pushed it out of my mind;

But I can’t forget, if I wanted to,

Four-Feet trotting behind.

Kipling’s poem is an elegy for his Aberdeen terrier, but such footnotes do little justice to a work of such intense feeling. The personal, intimate tone struck in that opening stanza testifies to the closeness between man and dog, for which Kipling’s tone is the perfect complement.

If you go back to ancient Rome, you find that even then dogs were the natural stimulus for poetry that drew on our most private reflections. Martial wrote more than half a century before the birth of Christ; he is the author of the first poem ever written about a lap-dog, Issa, owned by his friend, Publius.

When her bladder’s full to bursting,

She won’t let a drop touch the sheets, instead

Nudging him with her pawpad so that, when

Roused, he sets her on the floor, and lifts her

Back on the bed when she’s done. Innately

Chaste and modest, she’s a stranger to love,

No mate being equal to the tender

Young bitch. Lest the Grim Reaper remove all

Trace of her, Publius paints her portrait

Which is more lifelike than the dog herself:

Place them side by side, and you would suppose

Both the real thing or both works of art.

Once more, the poem is about that special, perhaps unique passion, that thrives between humans and their dogs. And Martial anticipates all the other dog-poets who are to follow by writing a poem in which Publius attempts to prevent Death from stripping him of the dog he loves so much.

Of course, that’s what all the dog-owners in this book wanted to do: the writing of poetry is as passionate and committed an attempt to preserve the beings we love as is the painting of a portrait. We should be grateful that people continue to do it, even if it cannot endow their dogs with the immortality we crave.

*

“Walking the Dog”

by Howard Nemerov

Two universes mosey down the street

Connected by love and a leash and nothing else.

Mostly I look at lamplight through the leaves

While he mooches along with tail up and snout down,

Getting a secret knowledge through the nose

Almost entirely hidden from my sight.

We stand while he’s enraptured by a bush

Till I can’t stand our standing any more

And haul him off; for our relationship

Is patience balancing to this side tug

And that side drag; a pair of symbionts

Contented not to think each other’s thoughts.

What else we have in common’s what he taught,

Our interest in shit. We know its every state

From steaming fresh through stink to nature’s way

Of sluicing it downstreet dissolved in rain

Or drying it to dust that blows away.

We move along the street inspecting shit.

His sense of it is keener far than mine,

And only when he finds the place precise

He signifies by sniffing urgently

And circles thrice about, and squats, and shits,

Whereon we both with dignity walk home

And just to show who’s master I write the poem.

*

“Vern”

by Gwendolyn Brooks

When walking in a tiny rain

Across the vacant lot,

A pup’s a good companion—

If a pup you’ve got.

And when you’ve had a scold,

And no one loves you very,

And you cannot be merry,

A pup will let you look at him,

And even let you hold

His little wiggly warmness—

And let you snuggle down beside,

Nor mock the tears you have to hide.

*

“The Power of the Dog”

by Rudyard Kipling

There is sorrow enough in the natural way

From men and women to flll our day;

And when we are certain of sorrow in store,

Why do we always arrange for more?

Brothers and sisters, I bid you beware

Of giving your heart to a dog to tear.

Buy a pup and your money will buy

Love unflinching that cannot lie—

Perfect passion and worship fed

By a kick in the ribs or a pat on the head.

Nevertheless it is hardly fair

To risk your heart for a dog to tear.

When the fourteen years which nature permits

Are closing in asthma, or tumour, or fits,

And the vet’s unspoken prescription runs

To lethal chambers or loaded guns,

Ten you will find—it’s your own affair—

But . . . you’ve given your heart for a dog to tear.

When the body that lived at your single will,

With its whimper of welcome, is stilled (how still!);

When the spirit that answered your every mood

Is gone—wherever it goes—for good,

You will discover how much you care,

And will give your heart to a dog to tear

.

We’ve sorrow enough in the natural way,

When it comes to burying Christian clay.

Our loves are not given, but only lent,

At compound interest of cent per cent.

Tough it is not always the case, I believe,

Tat the longer we’ve kept ’em, the more do we grieve:

For when debts are payable, right or wrong,

A short-time loan is as bad as a long—

So why in Heaven (before we are there)

Should we give our hearts to a dog to tear?

__________________________________

Dog-eared, an anthology edited by Duncan Wu, is available now. Credit to Alexander Nemerov, on behalf of the estate of Howard Nemerov, for permission to reprint “Walking the Dog,” and Pamela Williams, Client Services Manager for Brooks Permissions, for permission to reprint “Vern” by Gwendolyn Brooks.

Duncan Wu

Duncan Wu is Raymond A. Wagner Professor of Literary Studies at Georgetown University. He is also the editor, with Carolyn Forché, of Poetry of Witness (Norton: New York, 2014).