One of the many beautiful things about the trans body is that it’s built, not inherited. You author your form, edit it, decide what it is you want to keep and what you want to change. I have heard other trans people refer to their bodies as “vessels,” which I think is apt: it’s the thing with a head and a heart that carries your soul, and you can (and should) modify and bedazzle it all you want.

You are not it and it is not you. Cis people frequently make this mistake, treating their bodies as their identities and trying to modify them to fit some predetermined form. I want to ask them: why not let your body be what it wants to be? Why not cover it in sequins, drape it in gold lamé?

I had a large chest with what I referred to as “leaky” breasts: they sagged to either side when I reclined in bed, distractingly heavy like gallons of water in roomy plastic sacks. When they ached, I became worried that I had cancer. I dreaded the mammograms I’d soon have to get—the idea of one of my sacks flattened under a pane of glass made me uneasy. My breasts flopped and bounced when I ran, so much that I joked one of them was going to slap me in the face. Button-downs gapped when I tried to close them over my chest; t-shirts, too, were tighter on top than on bottom.

My breasts were a favorite of gravity’s: they sagged tremendously, and needed to be supported by industrial-strength bras I was too careless or annoyed to buy. Indeed, I was completely unsure of my cup size—I must have been a spacious E or F but persisted in the comforting belief that I was a C, and bought small bras with wire that dug into my sides and that I’d eventually donate to friends whose chests didn’t torment them to the extent mine did. Worst of all, I never felt like I could give a proper hug: the fleshy sacks stood between myself and my loved ones.

In June of 2020, I wasn’t sheltering in place alone. An old friend had come from the city to join me in my rural quarters: it was easier to stay home in the country, and there were fewer people to contend with. At that point my friend had been on hormones for just under a decade, and we would talk, bathroom door open, as she gave herself her weekly shot. The shots were subcutaneous: she pinched a bit of fat on her stomach and gently slid the needle in, never flinching or exclaiming like I knew I would have. These shots no longer hurt her, she told me.

I had watched her do this for years, but I was seized with a curiosity about the effects as I had never been before. When did she first start to notice changes, and what were they? Slowly, her skin had grown softer, her chest had developed, the veins had receded from the tops of her hands. How did she get the hormones? She’d gotten a prescription from an LGBTQ clinic in Chicago. She could refer me if I wanted.

“Maybe,” I hedged.

Conservatives claim transness is catching, and they’re right, but not in the way they think they are. Instead of spreading like COVID or smallpox, transness emerges at the sight of other trans people living happily in the world. Transness is an inborn quality—a beautiful quality—but it carries such stigma that it must be tended to and encouraged by other trans people who have, by some miracle, carved out a place in the world to live authentically.

Breasts always seem to belong to everyone but the wearer.And there I was, just weeks after my friend offered to refer me to the clinic in Chicago, Googling “trans man” and looking at photos of chests ribboned with scars.

“I don’t want breasts,” I said at last. My friend turned to me over the half-wall between the kitchen and the living room.

“Yeah?” she said.

“Yeah,” I said. “And I want to be a man.”

*

Without trans and queer elders, there would be no blueprint from which to build the structures we inhabit: the safe spaces created by surgery, activism, and chosen family. Without the trans men of the twentieth century, I would not have been able to make a case to any doctor—much less any insurance company—for the medical necessity of my top surgery. During my recovery, I decided I wanted to know who these men were.

In 1942, Michael Dillon became the first trans man to undergo a double mastectomy. Dillon was a sensitive person, a seeker of truth—born in Kensington, England, he’d spend the final years of his life as a novice Buddhist monk in India. Between his birth and premature death at 47, he would be twice publicly outed, once by a chatty psychiatrist and another time by a newspaper reporting on a discrepancy in naval records. Vexed and ashamed, Dillon abandoned his life wherever he was and moved somewhere new, where he passed effectively after years of testosterone therapy and no one questioned his gender.

Little is known of the doctor who performed Dillon’s top surgery, though it’s been suggested that it was a plastic surgeon by the name of Dr. Geoffrey Fitzgibbon. Fitzgibbon—if that’s in fact the doctor’s name—was a remarkable ally to Dillon. Dillon had entered the hospital after a hypoglycemic fainting spell and stayed a few days; while there, he happened to meet Fitzgibbon, who not only agreed to perform the mastectomy, but helped Dillon change his gender marker on his birth certificate and other identity cards.

This sort of luck seemed to happen frequently for Dillon: though he certainly met with plenty of transphobia in his lifetime, he also crossed paths with some trailblazing doctors who were happy to help him with his medical transition.

In his biography Out of the Ordinary, Dillon writes of his top surgery: “I was delighted from this operation when I had recovered from it. At last I was rid of what I hated most. I sat out on the verandah letting the sun help to heal the incisions.” Photos of Dillon before his top surgery show someone ill at ease in his body: he poses next to his brother in an ankle-length dress, he smiles nervously into the camera wearing a cloche hat. He seems happier with himself in the photos from St. Anne’s—Oxford’s women’s college—the short-haired, square-jawed captain of the rowing team.

Without trans and queer elders, there would be no blueprint from which to build the structures we inhabit.It’s likely that he was binding then, a process which relieves dysphoria but which few enjoy: flattening one’s chest takes significant pressure, and whether you’re wearing a binder or wrapping yourself with bandages (as Dillon must have done), you’re going to sweat a heinous amount and be very uncomfortable. Top surgery was obviously liberating for Dillon, as it is for all of us: no binding, no hiding, pure freedom.

In 1946, Dillon published Self: A Study in Ethics and Endocrinology. In addition to a detailed unpacking of the human endocrine system and the concept of free will, the book described the transgender experience before there were words for it: Dillon referred to “masculine inverts” born with “the mental outlook and temperament of the other sex.”

Self brought Dillon to the attention of Roberta Cowell, a British trans woman who was a former fighter pilot and race-car driver. Dillon, who had studied medicine at Trinity College in Dublin, performed an orchiectomy on Cowell, an operation that was illegal in Britain at the time. Dillon thought he’d found in Cowell someone who could understand and even love him. He wrote poetry for her and eventually proposed, but she rebuffed his affections. The two parted ways in 1951.

Sources are conflicted over Dillon’s death: some say he died suddenly on his way to Kashmir, while others claim he died in a hospital in Dalhousie after a period of declining health. What we do know was that he lived triumphantly in the body that best suited him. I think about this often, the joy Dillon claimed for himself at a time when trans surgeries were even more stigmatized than they are now. What love he had for himself, how thrilled he must have been to live authentically. It’s a feeling unlike any other.

*

Breasts always seem to belong to everyone but the wearer. Freud tells us that infants’ polymorphous sexuality is first expressed through their oral attachment to the breast, leading them to identify their mother as their first external “love object.” Media tells us that breasts are among the most important thing any woman can have, and that they should be full and perky and grabbable. Breasts nurture infants, feed sexual desires: nipples are sucked for both milk and pleasure. One can start to feel like a Christmas tree, branches sagging with ornaments for others to ogle and touch and break.

A very witty friend of mine, a trans woman, once told me that breasts are like boats: fun for a ride but a hassle to keep. This has been true for many of my friends who have breasts—they sweat and chafe, they cause back problems, they become a “uniboob” when squished into place by the wrong sports bra.

My partner, a nonbinary person who also had top surgery, frequently received compliments on their “great tits,” which they resented. “And these compliments were coming from fellow trans and nonbinary people,” they told me, a look of disappointment on their face. Even the most gender-enlightened among us still see breasts as objects of pleasure without a second thought given to their (oft beleaguered) wearer.

I was lucky: I only had to bind for a year, and only after I realized I needed top surgery. Binding did little for me other than create a blunt lump on my chest, and that was when my breasts managed to stay in the binder or under the TransTape. All too often they leaked or flopped out, insistent, pernicious—knowing, perhaps, that their days were numbered and wanting to make some kind of vindictive statement.

The day of my surgery, the plastic surgeon—a small and imperious man who often posed with his toy poodle on Instagram—drew lines across my chest in Sharpie, marking where he would cauterize my flesh and sew on fake nipples. He held one breast in his hand, made some markings on it, and let it flop down, then did the same for the other. He told me impatiently to calm down, which had the exact opposite effect on me. Then I was on a gurney being dosed with Ativan, worrying to the anesthesiologist that the dose wouldn’t be sufficient to knock me out.

I often roll my eyes when trans people are described as brave, but it’s really true in the case of Lou Sullivan.And then I was awake, my chest sealed under a binder. I was rushed out of the surgery center and into a friend’s car, and then we proceeded back to our Airbnb. For days I sat on a slim leather couch of a kind heavily unsuited to top surgery recovery, watching the same episodes of Succession over and over and fretting that what I’d done would have no effect on my hopelessly low self-esteem. I worried, as I often had, about my weight, my skin, my hair. A part of me was lagging, still trapped in my “cis” body. It wouldn’t be until two weeks later that I’d discover the joy of being trans.

The cis have got transness all wrong—but who’s surprised? We’re sexualized, reduced to genitalia and flashpoint conversations about bathrooms and perversion. We’re assumed to always be miserable and dysphoric. In truth, some of the happiest people I know are trans, and that’s because we’ve built our happiness from the ground up, making our exteriors match the particularities of our interiors.

When I emerged from my post-op fog, I was shocked and overwhelmed by how great I looked. I took shirtless selfies—too many to count—and felt my posture improve, my heart creak open. My partner, who had gotten their top surgery two weeks before mine, held me in bed: we had just begun to date, but we could already recognize how bonded we were by the scar tissue forming in our chests. We talked about how medieval it was to get your breasts sliced off, and how great it would be if all trans kids had access to puberty blockers. My partner has an enchanting smile and gives incomparably warm hugs. As I was falling in love with them, I was falling in love with myself, too.

*

Before Elliot Page and Gottmik, there was Lou Sullivan. Sullivan was born in 1951 and grew up Catholic in the town of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. He kept journals from the age of 10 until his death of AIDS at age 39. The journals, which contain outdated words like “transvestite” and “crossdresser” and describe cruising in the gay bars and public bathhouses of 70s and 80s San Francisco, keep Sullivan frozen in time. A trans and queer boomer, he was a radical by default.

For years, Sullivan lived in the territory between binaries, going to work in a dress and coming home to change into slacks and a men’s undershirt. His desire to be a gay man was incipient: he was thrilled when his boyfriend—referred to simply as “J” in his journals—was called a fag by a group of teenagers on a Milwaukee street.

When he and J broke up, Sullivan pursued hormone therapy and sexual reassignment surgery, but he couldn’t get any of the gender clinics to take his case on. “I had a lot of problems with the gender professionals saying there’s no such thing as a female to gay male,” he said in one of a series of interviews he gave to psychiatrist Ira B. Pauly between 1988 and 1990. But Sullivan was anything if not persistent, and was finally able to get his top surgery in 1980.

On preparing for the surgery, he writes: “To wash my body with surgical soap, according to instructions, washing, washing, and watching my body that is there, that isn’t there, that won’t be there in 3 days. How can I share this emotion; how can I find an outlet for these incredibly strong feelings?” In conversation with Dr. Pauly, he says: “[The mastectomy] was really nice. It was so good… Finally I could take my shirt off, I could breathe, I didn’t have this binder around me all the time.”

I know what Sullivan is talking about in both cases. I, too, washed my chest with surgical soap three nights before my surgery—I, too, contemplated what felt like the amputation of a stubborn, vestigial limb. And after the surgery, the air felt easier to breathe, the ground softer to walk on. I didn’t realize how trapped I’d been, how right transness was for me. This was the difference between Sullivan and me: for years he had a clear vision for himself, an inborn knowledge that he was a gay trans man. I, on the other hand, stumbled into my identity on the same day I decided I needed surgery. But then there’s no right path to the truth.

Sullivan was an activist. Little had been said of the transmasculine experience in his time—especially the gay transmasculine experience—so he took to writing about it. He wrote newsletters for F2M, which was described in a mailing from 1989 as “a newly formed support organization created by and for female-to-male transsexuals/crossdressers.” He was a founding member of the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society, to which he donated his photos and papers upon his death.

These miscellany have been posted on the OutHistory website, and they’re quite revealing. Here’s a photo of Lou completely naked pre-top surgery, eyes closed and mouth tight as if he’s holding his breath. And here he is after top surgery: chest flat, scars healed, smiling comfortably. In one of his few clothed photos post-surgery, he’s relaxed in an armchair, holding a beer, legs crossed with a serene look on his face. He appears profoundly comfortable in his skin.

In December of 1986, Sullivan was diagnosed with AIDS and told he had 10 months to live. Though the news must have been devastating, it had a silver lining: “I took a certain pleasure in informing the gender clinic that even though their program told me I could not live as a Gay man, it looks like I’m going to die like one,” he wrote. In the videos he filmed with Dr. Pauly, Sullivan withers away.

In 1988, he looks like the kind of healthy, mustachioed queer you’d see in stonewashed jeans and a white t-shirt at an ACT UP meeting. By 1990 he’s practically a scarecrow, his rodlike neck emerging frailly from the roomy collar of his dress shirt. Even in the throes of death, he wanted to destigmatize his condition. “I think it’s really important that people do talk about [AIDS], be upfront about it, try to educate,” he told Dr. Pauly.

I often roll my eyes when trans people are described as brave, but it’s really true in the case of Lou Sullivan. In an era when the gay trans man was publicly unaccounted for, he spoke about his experience. He blazed a trail that those like me and my contemporaries have followed. And for that I am incredibly thankful.

*

Both of the early recipients of top surgery I’ve discussed have been middle- to upper-middle-class white men. There are obvious reasons for this—reasons we all know well by now—and it should be noted as well that trans surgeries remain expensive and frequently inaccessible to working class people. In the top surgery groups I’m in online, photos of people of color are far and few in between—people in larger bodies are more often accounted for, but they, too, face significant fatphobic barriers to surgery. I myself am a professor and writer who makes money off my day job and my books: surgery was accessible to me.

My partner, on the other hand, would not have been able to get surgery had Illinois Medicaid not covered it, and the same goes for many people I know. It’s my dream to one day become rich enough to donate thousands of dollars to the many top and bottom surgery GoFundMes that are floating around online, especially those of marginalized people. I want to do my part to make all trans surgeries as cheap as possible. Realistically speaking, all trans surgeries are necessary and life-saving, and they should be free to everyone who needs them.

I got top surgery in July of 2021 and began taking testosterone in November of that year. My voice has deepened and I’ve started to grow sideburns and hair on my knuckles. My jaw has squared and I’m slowly beginning to see the veins in my hands. I don’t look much different in photos unless I’m unshaven: then you can see a small, teenaged goatee on my chin and traces of a mustache.

I identify as a nonbinary trans man because, while I am transmasculine, there are also aspects of me that are uncategorizable: he/they-ness radiates off me. It’s a vulnerable thing to go through puberty as an adult, a reminder of your inevitable visibility as a trans person. But it’s an indescribably lovely experience at the same time.

Top surgery opened me up to my life—I didn’t realize the extent to which I’d been sleepwalking through it. I had resigned myself to hating my body and obsessing over its fluctuations. Now I could care less what shape my body takes or how I look in photos. I’m mercifully at peace. I’m grateful to my friend and her subcutaneous estrogen shots; I’m grateful to the many trans men who made themselves visible online.

I’m grateful to men like Michael Dillon and Lou Sullivan whose euphoria is well-documented in the annals of trans history. I’m grateful to myself, that fragile and scared person once puny with self-hatred—grateful that he found a way out of the thicket of his confusion and self-doubt. I’m grateful for my emergence into the world, and I’m grateful to be home.

__________________________________

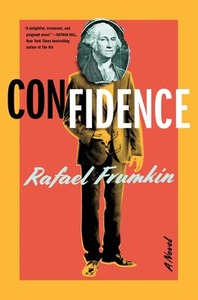

Rafael Frumkin is the author of Confidence, available now from Simon & Schuster.