The Beatles Adventures in the Red-Light District: On George Harrison's First Time

“My first shag was...with Paul and John and Pete Best all watching.”

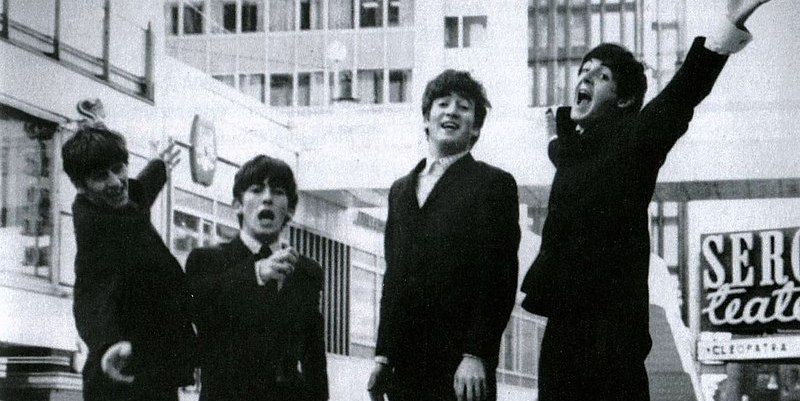

The Beatles’ first stay in Hamburg, between August and November 1960, is the most romanticized episode in their career. Irresistible that vision of brash boy troubadours in their cracked black leathers, blasting out raw rock ’n’ roll among the strip clubs and sex shows…fumbling amateurs forging themselves into hardened professionals…the apprenticeship in the underworld without which their later flight through the Heavens could never have been.

From a twenty-first-century perspective of health and safety and employee-protection, it reads more like people-trafficking, with guitars. Hamburg had a historic affinity with Liverpool, both located in the far north-west of their respective countries and both seaports, thronging with each other’s shipping like neighbors who could walk in without knocking. The difference was that Hamburg had a red-light district called the Reeperbahn whose name even the bawdiest Liverpool sailors spoke with awe.

A large part of the Reeperbahn’s business came from West Germany’s military bases, both American and British, on standby to counter the expected nuclear attack from the Communist East. The clientele were mostly young men whose idea of a good time, as much as getting drunk and laid, was live rock ‘n ‘roll. Hamburg’s porn merchants therefore began importing music groups from its mercantile soulmate, and for a time the sole exporter was Allan Williams.

Earlier in 1960, Williams had contracted to supply one of the bands he—sort of—managed to a Reeperbahn club-owner named Bruno Koschmider. He sent Derry and the Seniors, acknowledged to be Liverpool’s most dynamic live act with their Afro-Caribbean vocalist Derry Wilkie.

They went down so well at Koschmider’s Kaiserkeller club that he requested another band exactly like them. Williams’s first choice, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, were already committed to a residency at a Butlin’s holiday camp; his second, Gerry and the Pacemakers, turned him down flat, so in desperation he turned to the Beatles. When the news reached Derry and the Seniors in Hamburg, their sax-player, Howie Casey, wrote to Williams, protesting that such a “bum group” would be a severe embarrassment to them.

But the Beatles couldn’t take the job without a drummer, nor could Paul continue in the role since Koschmider wanted a five-piece line-up like the Seniors. John briefly considered making Royston Ellis the fifth member as a “poet-compère” as if he expected their Hamburg audience to resemble some earnestly attentive students’ debating society.

Hamburg had a red-light district called the Reeperbahn whose name even the bawdiest Liverpool sailors spoke with awe.

This time, no long, dispiriting search was necessary, for the ideal candidate materialized at Mona Best’s Casbah Club in West Derby, where George had saved the Quarrymen from disintegrating a year earlier.

It was during their Casbah residency that Mrs. Best’s good-looking son, Pete, had first become interested in rock ’n’ roll, and after their petulant exit he’d formed a group named the Blackjacks, with himself on drums, to fill the gap they’d left. Now John, Paul, and George came back looking for a drummer just when Pete’s adoring mum had bought him a sumptuous new kit in a blue mother-of-pearl finish from the Blacklers department store.

So, one could say that George and his old-apprentice-masters were jointly responsible for Pete Best becoming a Beatle—an experience that was to leave Pete with the saddest eyes in rock.

Allan Williams smuggled the new quintet into West Germany by road, without work-permits or any kind of official documentation but their passports. If challenged, Williams said, they were to pretend to be students on vacation. To compound the illegality, George was seven months shy of eighteen, the minimum age for entry to the Hamburg clubs where they’d be performing. And alone among the five traffickees, and constantly teased about it, he was still a virgin.

The city’s St. Pauli district, of which the Reeperbahn is the main thoroughfare, came as a profound shock after Liverpool’s general nocturnal blackout and quiet. Continuous neon lights shimmered and winked in gold, silver, and every suggestive color of the rainbow, their voluptuous script—bar monika, mambo schankey, gretel & alphons, roxy bar—making the entertainments on offer seem even more untranslatably wicked. This was a place with no distinction between day and night, which would turn the Beatles’ body-clocks upside down forever.

Their new employer, Bruno Koschmider, proved to be a tiny man of indeterminate age with the face of a carved wooden puppet, a femininely frothy coiffure, and a limp supposedly acquired during wartime service with Hitler’s Wehrmacht. But if Koschmider seemed to have stepped straight out of a Grimm’s fairy tale, his Kaiserkeller club was spectacular, a subterranean barn decorated on a nautical theme with booths shaped like rowing-boats, lifebelts, brass binnacles, and ornamental rope-work.

Only now did they learn they weren’t to play here at the heart of the Reeperbahn but in a run-down strip club called the Indra that Koschmider owned in Grosse Freiheit, meaning “Great Freedom,” a much less buzzy side-street. Their job was to turn the Indra into as big a crowd-puller as Derry and the Seniors had made the Kaiserkeller.

Worse was to follow when Koschmider took them to the living quarters he was contracted to provide. Around the corner in Paul-Roosen- Strasse, he owned a small cinema called the Bambi, showing a mixture of porn flicks and old Hollywood gangster movies and Westerns. The Beatles’ quarters were behind its screen; one dingy concrete room and two glorified broom-cupboards with camp-beds and naked overhead light-bulbs, exactly the kind of hell-hole regularly uncovered nowadays, packed with desperate illegal immigrants.

The only washing facilities were the adjacent cinema toilets. George would later say this hadn’t been as hard on him as on the others “because I used to live in a house without a toilet.”

In all its various incarnations back in Liverpool, the band had never been on any stage for longer than about twenty minutes. At the Indra Club, they found they were expected to play for four and a half hours each weeknight in sets of an hour and a half with only three thirty-minute breaks. On Saturdays and Sundays, it increased to six hours.

On the Beatles’ opening night, in matching lavender- colored jackets tailored by Paul’s next-door neighbor, it was made plain that they had to do more than just stand there.

Unlike the Kaiserkeller, the Indra wasn’t a dance-hall; its few customers sat at tables and watched an act, previously a stripper named Conchita. And on the Beatles’ opening night, in matching lavender- colored jackets tailored by Paul’s next-door neighbor, it was made plain that they had to do more than just stand there.

Bruno Koschmider and Allan Williams acted as warm-up men, in this case to warm up the performers rather than the audience. “Mach Schau!” Koschmider shouted in peremptory German fashion, clapping his hands. “Come on, lads, make it show!” Williams translated.

In Liverpool, to “make a show” of someone means to mock or humiliate them. John, characteristically, took it that way with a take-off of Gene Vincent as he’d appeared at Liverpool’s boxing stadium only days after the Eddie Cochran death-crash, stomping around the stage and rolling on the floor in heartless mimicry of Vincent’s calipered left leg. One night, he appeared onstage in shorts and, halfway through a song, pulled them down and showed the audience his bare bottom; not just in a “flash” but an extended view. Blissfully unaware they were being made a show of, the audience loved it.

To fill the daunting ninety-minute sets, George recalled, they needed “millions of songs,” going far outside rock ‘n’ roll to Country, folk, blues, even Broadway show tunes and the current pop hits. Every one would be padded out to around twenty minutes and have about four instrumental breaks, either by him or Paul on the house piano; Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say” could be stretched like a piece of chewing-gum to almost an hour in itself.

Their great standby was the prolific Chuck Berry, whose elegies to American high school life seemed not in the least weird from a beady-eyed man with a golf-club mustache in his mid-thirties, and whose framing guitar riffs were the most seductive since Buddy Holly’s. George could soon reproduce them all, even the finger-tangling solos like two players dueling in “Johnny B. Goode.”

During the few hungover hours between shows, they’d try to grab some sleep in their ratty beds at the Bambi Kino or wash their clothes in the toilets they shared with a constant stream of cinema patrons. Even the fastidious George soon gave up the struggle to keep clean. “I never used to shower,” he remembered. “There was a washbasin in the lavatory…but there was a limit to how much of yourself you could wash in it. We could clean our teeth or have a shave. I remember once going to the public baths, but they were quite a long way away.”

There were already tensions within the band, magnified by the stress of being in a strange country and worked half to death. John’s leadership remained unchallenged, but Paul was ever his zealous adjutant; convinced that they could be spotted by some talent scout at any moment, he called for maximum effort, however late the hour or sparse the audience. And Stu Sutcliffe’s bass playing, though now reasonably competent, was clearly never going to satisfy Paul.

Then, Pete Best was no longer regarded as the eleventh-hour lucky break without whose sparkly blue drums they wouldn’t be here at all. Pete was a thoroughly amiable character who endured the hours he had to work and the conditions at the Bambi Kino with unfailing cheerfulness—yet something about him somehow didn’t fit. The problem would later be said to be his playing, but he produced a pounding rock beat more than adequate for a noisy club and a solid underlay to George’s lead guitar. Only recently, George had written to a friend in Liverpool that “Pete is drumming good.”

More tellingly, he was the best-looking member of the group, his crisp-cut hair and brooding expression giving him a look of the Hollywood matinee idol Jeff Chandler. He was the only one to have a stripper as a girlfriend, so spent most of the band’s meager time off with her instead of sharing in their adventures and misadventures. The German word for him was “reserviert” and it had already started to be his undoing.

The most famous Reeperbahn story, told and retold in Liverpool dockside pubs, was of women being mounted by donkeys with washers around their penises to limit penetration. Although this new definition of donkey-work proved a myth, there were other sights to awe a seventeen-year-old whose experience of erotica had been limited to British “tit” magazines like Razzle with all the nipples blacked out.

In some clubs, George could see men and women of every race and color have sex in twos, threes, or even fours, in every possible and improbable configuration; in others, he could watch nude women wrestling in a pit of mud, cheered on by plump businessmen tied into a communal bib to protect their suits from the splashes. At Bar Monika or the Roxy Bar, he could meet trans men as beautiful and elegant as Parisian models; around the corner in the Herbertstrasse, he could find shop windows displaying sex workers as living merchandise complete with price tickets.

There George finally lost his virginity, the total lack of privacy turning it into a formal initiation.

Sex was the Reeperbahn’s main recreation as well as business and to its female population, jaded by years of drunken sailors and furtive businessmen, a young and relatively inexperienced young Liverpool rocker was the tastiest of novelties. As the Beatles built a following at the Indra Club, they found themselves repeatedly propositioned both by women customers and their fellow employees.

It was done in a forthright manner that might be said to have antedated Women’s Lib by a decade. Someone who fancied a bit of boy Liverpudlian would make her choice while the band was playing, either by pointing him out like a restaurant customer selecting a live lobster or, if stage-side, reaching up to fondle his leg. Many dispensed with even these slight formalities, going straight to their slum quarters at the Bambi Kino and waiting in one or other bed until their entrée arrived.

There George finally lost his virginity, the total lack of privacy turning it into a formal initiation. “My first shag was…with Paul and John and Pete Best all watching,” he would recall. “We were in bunk beds. They couldn’t really see anything because I was under the covers but after I’d finished they applauded and cheered. At least they kept quiet while I was doing it.”

______________________________

George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle by Philip Norman is available via Scribner.

Philip Norman

Philip Norman is the best-selling biographer of Eric Clapton, Buddy Holly, the Rolling Stones, John Lennon, Elton John, Mick Jagger, and Paul McCartney. A novelist and a playwright, he lives in London.