My first eagle: South Dakota, Highway 385 out of Deadwood, late morning, November. I was hoping for it, since I’d never seen one before. My friend slowed the car and pointed up and said, “There’s your eagle.” At first, I heard “seagull” (I grew up on Long Island and gulls are all over) but the shape wouldn’t clarify—too much hook, too much curve—and I fast reheard “eagle.” In my pocket was a quarter, which later that day I’d resee as an amulet, a way to keep belief near: E pluribus unum, “Out of many, one” (the words sit like a hat on our eagle’s head), likely a variation on a fragment by Heraclitus: “Out of all things, one, and one out of all things.” As a slogan it predates “The melting pot,” which in my child’s eye I saw as an actual kettle suffering a too-high heat, collapsing, forming a molten puddle—impossible to unimagine now, and which somehow meant my country.

Flying low over the highway, the bird was so close it had actual feathers (not embossed, not etched) and a neck it turned to better see us. Or not us, but whatever it might clean up, pick at, side of the highway, freshly killed. Either way, as it angled its head, feathers parted and there was a gap, a tender dark spot where a little chill must have hit, as it does for me when I turn a corner and the wind lifts my hair, finds my neck, and slips in.

*

Ben Franklin didn’t think much of the eagle. (Bald, by the way, is from piebald—two-colored, the white head and tail against the dark body.) He wrote, in a well-known letter to his daughter:

For my own part, I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this injustice he is never in good case, but like those among men who live by sharping & robbing, he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides, he is a rank coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district.

*

My second eagle came forth as a feather. A friend showed it to me, lifting the lid of the cedar box where she kept it, where I wasn’t sure it wanted to be; it looked pretty cramped, if I may describe the feather as I would have long ago, when the line between objects and beings had not yet been drawn, and all was alive, and felt, and capable of holding a conversation or being hurt. But, then again, sacred shards of bone, teeth, fingernails, locks of hair have always been made to live in such boxes. I don’t think there were colored beads or decorative wraps on the feather (I almost said “on the bird”) since a relic, by a kind of mitosis, regenerates spirit, so there exists between part and whole a very fast shimmer that blurs and joins both. What did the feather do in there—rest? Until called upon? What is the life of a sacred thing, beyond waiting to be called forth? Though, too, I believe we are necessary, and that restive powers need to be touched, moved, acknowledged into being. And that the act of enlivening matters.

*

Eagles certainly look ferocious, confident, full of pride: those sharp talons for seizing and beaks for tearing, puffed breasts (though many birds puff up in the cold) and blazing, ever-open eyes (almost human-sized, though four times as sharp). Our country’s symbol very much isn’t the screech owl, a creature the size of a coffee mug, whose habits include attentive waiting, silent diving, erratic flight to confuse its prey, and whose call sounds not at all like a screech, but a distant, whinnying horse. Whose eyes are a buttery yellow, and gently bright. I’d be inclined to choose for an icon a bird who won’t much reveal itself, who is shy and alert and requires patience to get to know. Such is the way the best thought comes—over time, very slowly.

Such are the habits of being I’d seek in a national bird—a watchful thing who prefers the edges, who leaves behind a scoured bounty of bones, teeth, and feathers, returned to the earth in neat pellets.

Yes, a screech owl, if I had to go for a singular creature—though it might be better to consider the full expression of our motto, and restore to the epithetic “Out of many, one” the phrase “and one out of all things.” We might then have a more capacious illustration of how we actually live together. Consider Lewis Thomas’s description of ants, those aggregating minds: “What makes us most uncomfortable is that they . . . seem to live two kinds of lives: they are individuals going about the day’s business without much evidence of thought for tomorrow, and they are at the same time component parts, cellular elements, in the huge, writhing, ruminating organism of the Hill, the nest, the hive.”

On the coin of my realm: heads—a screech owl; tails—a ruminating hive.

*

It’s that the eagle is a rock star, and I’m not a fan type. Where crowds gather, I run the other way—toward buzzard, crow, sparrow. The rabble. The common. Definitely the pigeon. Not the brook-voiced mourning dove with its slow grace and musical flight; I mean exactly the city pigeon, oily and bright as a gas station puddle, and not at all bothered by spiked window sills, or ledges sown with shards of glass. Who never hurries, who dodges buses at the very last second, resettling itself in the same perilous spot.

*

My third eagle—an eagle pair, so alike in their fate I can discuss them as one—came a few weeks ago at a small, county zoo in New Jersey. They lived in a well-kept cage enclosed by special, tangle-resistant mesh. At the center was a high platform piled with sticks, the makings of a nest the keepers started, but which, not being mates (pals, yes, they got along fine), the birds wouldn’t finish. Eagles don’t much like open platforms, and their courtship displays require high, aerial loops, a clasping of talons, a plunge towards earth and quick release. As their keeper said, netting kills the mood. Both were rescued (unintentionally shot, their vision went bad and their wings didn’t heal) and couldn’t be released into the wild.

Or what would happen?

They’d die. Which is, of course, what happens to all birds with lousy sight and bad wings out in the world: they can’t hunt well, they bump into things, and turn fast into prey. The longer I looked on—the neat cage with perches and fresh mouse meals—the harder it was to see them as birds, for all the good they’d been done.

*

At the National Eagle Repository, in Commerce City, Colorado, the bodies of dead eagles are collected, cataloged, and frozen.

It’s illegal to keep a dead eagle, even if just come upon (say, electrocuted or hit by a truck), so if it’s your practice to use eagle feathers in ceremonies, to use talons in dances, or bones, or skulls in prayer, you must first petition the government for the use of any eagle parts.

A bulletin put out by the US Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Law Enforcement answers questions about the procedures for procuring. “Only enrolled members of Federally recognized tribes can obtain a permit from FWS authorizing them to receive and possess eagle feathers from the Repository for religious purposes.” On the application “specify whether you want a golden or bald eagle, a mature or immature bird, a whole bird or specific parts, or have no preference” and “make sure you request either a whole bird or parts. Do not ask for both.”

There is also an “approved ceremonies” list, though you’re not required to name the religious ceremony if doing so “violates the sanctity of your belief.”

Applicants are advised of the long waiting period for birds (for the immature golden eagle, the most in demand, at least five years). There are over five thousand people on the waiting list for the approximately one thousand eagles the repository receives annually. Other wait times include: whole tail only, golden eagle: four to four and a half years; whole tail only, bald eagle: two to two and a half years; pair of eagle wings, approximately one year; trunks, heads, talons only: on receipt of request.

The form is highly specific, so as to carefully dole out birds. “Each applicant can apply for only one whole eagle or specific parts equivalent to one bird (i.e. two wings, one tail, two talons) at a time. Quality may vary. Applicants may not customize orders.” (The emphasis is theirs.) Since only one order per application is allowed, to obtain feathers to present to students at graduation, “an applicant may reorder and continue to do so throughout the year until the number of feathers needed have [sic] been acquired.” (Which would make high school graduation planning a year-round task—an undue burden in any court of law.)

That an allotment cannot be customized means take-what-you’re-given (as with government cheese), means make-do-with-salvage, or with the ersatz. A site called Real Legal Feathers sells turkey feathers as “a great alternative” and claims “you can wash, dry and preen the web back together just as you would any other natural feather.” (Perhaps—and this seems like a reasonable conjecture—if suddenly there was a scarcity of crosses, if crosses were no longer legally available, couldn’t one make do with an X? Which is, after all, a sort of cross on its side, a little tipsy and slightly askew, but squint and tilt your head and it’s more or less the same thing, no?)

If feathers are earned through deeds, if feathers are the deeds themselves, if eagle trapping sites are sacred and the hunt is undertaken after intense prayer and fasting—and if one must now apply to the government for feathers and parts—how does the sacred proceed? The following-of-directions and checking-of-boxes confers no story, no morning-full-of-anticipation (or weeks, or years), there ’s no suspension-of-thought-while-tracking, no wind-lifting-eagle and wing-sound-ceasing, the breath of the bird not-gone-but-shifting, the finding-and-entering, the listening-into. . . . If what’s as holy as the actual bird is the getting of the bird, if the holy needs for expression a season, death, or occasion, then the filing of forms, and before that even, the freezing, thawing, picking, and packing of eagles recomposes the shape of time.

And made to wait, the holy frays.

*

Of a carved, white wooden bird, an elaborate cutout art practiced in Baltic countries, John Berger writes: “One is looking at a piece of wood that has become a bird. One is looking at a bird that is somehow more than a bird. One is looking at something that has been worked with a mysterious skill and a kind of love.” Not so much a symbol of a bird, but an effort “to translate a message received from a real bird.” A teasing out of qualities. Not an imitation, but a glimpse, an attempt. As his language, too, is an attempt—each repetition of “one is looking” a return to the beginning, a trying-again, a reconstituting in different angles of light, so that by multiple views one might draw closer to. The bird’s not a fixed symbol, but an expression of something hard to catch hold of.

Feathers of wood.

A tree becoming the thing it sheltered; a bird expressing blossoming.

The qualities of one becoming the qualities of the other. A variation: In one thing, many.

*

My fourth eagle was a gathering of birds at the Conowingo Dam, near the spot where the Susquehanna River empties into the Chesapeake Bay. While I didn’t see nests, I assume they were there (December is nest-building time for eagles), huge ones, up to thirteen feet deep, and eight feet wide, and weighing more than a ton. That’s the size, in my neighborhood, of an average garden shed filled with stuff. I did see more than a dozen eagles, hanging out on rocks in the water, settling in trees, stretching their wings, resting and sunning themselves on transmission towers sunk into the river—not at all the solo creatures I assumed, portrayed as they are in heraldic portraits. (Poland’s double-headed eagle always looked like a filleted chicken. And pinioned on the quarter, our eagle’s legs are strangely squat, its broad chest pectoraled and unnervingly human. In fact, if you cover its wings with your thumbs, the bird looks like a cartoon prizefighter.)

I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character.Unlike black vultures, elegant flyers who coast on thermals, eagles flap a lot and land heavily on bare, sturdy branches. A few times a day at the dam, fish get caught in the turbines and sucked through—so the eagles pluck all they want from the water and hardly have to leave their rocks. They were to me—well, many things. Bigger than I remembered, more wary than the vultures who hunched on low branches and regarded us mildly. Mostly, though, they weren’t ferocious, just quietly sunning themselves on that unseasonably warm day. Close up, their beaks were more rounded than hooked, their legs softly feathered, their brows not so heavy—and mussed rather than stern. Maybe because it was so warm, and the breeze so gentle, their eyes seemed a sunny, polleny yellow. With my binoculars, I could see the scales on their talons, some muddy or browned with fish guts, some wet and shining. If I went in closer still, I’d see mites gathered under wing, bits of feather, fungi, and algae. In whatever ways eagles have seemed standoffish—these were not. These stretched and scratched and breathed.

Proximity turns a symbol into a bird again.

*

My final eagle began as an absence, as no eagle at all. Visiting the county dump, where I thought I might see one, turned up instead a lot of hawks. I drove in past the line of cars waiting to deposit household items and parked near the dumpsites, where I got out and looked around. Holding the hawks in my binoculars’ lens, I followed them across the very blue sky until they circled higher and turned to dark Vs, backlit by bright sun. The buzzards who tip so gently in wind, swallows skimming the dunes, mockingbirds, grackles, red-winged blackbirds—all moved in and out of sight. It was quiet up on the hill where the bulldozers were parked, and the county keeps pyramids of pipes and old oil drums. I could see the quarry and mulch pit from there, and all around the pear trees in bloom. In the knee-high grass, I surprised a woodchuck who exploded like a brown geyser and ran off fast, its heavy, loose pelt sliding over its back—the word pelt as surprising as the animal itself.

There was a peace to the far clanking and grinding, muffled by low, grassy hills, and when the machines stopped for the day, a warm, buzzing stillness rose up again, until the cars started their engines and lined up to leave.

No eagles that day, but now that I’ve seen more than a few, the thought of one in this summery spot, the thought of it whole and unto itself, made for me a ghost bird. An afterimage. Or a presaging—how can I know what might come to fill this place once I’m gone? A very real bird—here somewhere. Not threatened/ protected, not doled out in parts; not embossed, not marked on a personal checklist. Not derided or rescued. Not burdened with the ideals of a nation. Just yesterday, after reading about two eagles tangled in combat and crashing to earth at an airport in Minnesota, I went out expecting maybe—a sign? There was no eagle on our block that morning (and likely there won’t be, here in the city), but instead a sensation, a space in the air in eagle form. It’s hard to explain what it felt like—lit, present, ripe—what was that?

Consider the shape of a thought unbound, bound for a moment in the shape of a bird. Then let it mean—not luck, or luck’s opposite, not a stranger’s arrival, or the promise of riches. To see an eagle, and not a symbol, you’d have to stop wanting the bird to mean.

Such an empty, bright, high-domed sky. Put an eagle in it. A scrap, a dot, a spot on sun, smudge in air moving fast out of sight, gone behind trees then back out into light. Give it desires. Its own. What are they? What would an eagle want most from a day?

____________________________________

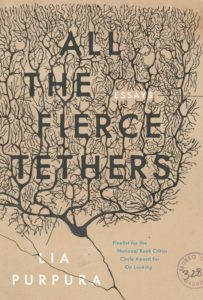

Excerpted from “Eagles” in All the Fierce Tethers. Used with permission of Sarabande Books. Copyright 2019 by Lia Purpura.