Featured image: Belle Delphine on an episode of the Cold Ones podcast.

When I wrote “Like and Subscribe”—the second-to-last story in Bugsy & Other Stories—I fully intended it as fan fiction about Belle Delphine, the e-girl who has ingeniously exploited the peccadilloes of horny gamer dudes to the tune of millions, both in terms of followers and personal wealth (though it could be argued that those categories are fairly fungible in a world as digital as Delphine’s).

I don’t doubt “Like and Subscribe” will join a robust canon of Belle Delphine “fic” for which I’m sure many an NSFW Tumblr and furtive anonymous Wattpad account have been created, but my story is probably quite different in its lack of imaginative extravagance. Instead of positioning Delphine as the waifu in an obscure anime or a sexy alien come to colonize Earth, I’m imagining a likelier scenario for her: on the same night that her reply guy stalker traces her IP address to her condo and decides to ask her to marry him, she discovers that she sees her best friend as more than just a friend.

The story is about many things—parasocial relationships, how women are perceived both on and offline, how the expectations of capitalism and patriarchy can be leveraged to the advantage of the very people both systems are designed to oppress—but it’s also a fan letter to Delphine, a kind of game-recognize-game from someone who aims to subvert with his art, and who strongly resonates with the subversion in hers. To me, Delphine is more than just a business-savvy e-girl troll who knows how to go viral on TikTok: she’s a true performance artist, as worthy of gallery space as someone like Marina Abramovic.

In facts, it’s Delphine’s Abramovic-like qualities that have shaped my fan fiction about her. I wanted to write a story that, like Abramovic’s The Artist Is Present, shows us two sides of a widely-admired creative mind: the “always on” performer and the vulnerable woman behind the mask—i.e. the widely speculated-about person obscured by the persona whose essential unknowability drives public interest in her art. Abramovic has always done a masterful job of toying with public expectations of her, managing the seemingly impossible highwire act of baring all and remaining in many ways a blank canvas. Delphine does the same, while also blurring the lines among performance art, softcore porn, and the nebulous, Zoomer-y category called “content creation.”

*

Belle Delphine is a fin-de-siècle-born Zoomer who, like many members of her generation, has a digital footprint spanning nearly half her life. This means that the truly curious can find the YouTube channel she created as a kid named Belle Kirschner: said channel has only 311 subscribers—though the three videos have views in the thousands, numbers which likely accumulated as a result of the fame she’s achieved as an adult.

One video, called “youngest swing artist x,” features a preteen Belle pulling off some truly acrobatic and impressive moves on a tree swing, and I’ll admit that the pearl-clutching mother hen in me spiraled a bit at the thought of her current audience finding this video and judging her for it. Though, knowing Delphine’s work, I imagine she’d find a way to make this, too, a part of her life’s great raised middle finger of a performance.

Delphine is more than just a business-savvy e-girl troll who knows how to go viral on TikTok: she’s a true performance artist.Delphine’s early life, as pieced together from rare moments of unironic self-disclosure in her videos as well as the few interviews she’s conceded to granting outlets like The Guardian and Vice, is both highly relatable and not. Relatable in that she was bullied by her schoolmates and spent a good deal of time alone, that she posted low-res cosplaying photos to various social media accounts, worked odd jobs, and was clinically depressed. Unrelatable in that she was buried deep in the many valences of an extremely online culture defined by a so-ironic-it’s-unironic horseshoe effect that would probably mystify most people born before 1995.

It certainly mystifies me: upon reading that she counted YouTubers such as iDubbbz and Filthy Frank among her chief influences, I looked up videos by both and found them by turns boring, inchoate, and mildly repulsive (though Filthy Frank is a pretty decent musician). Even though both iDubbbz and Filthy Frank are closer in age to me than they are to Delphine, they seem to be part of a vanguard that has heavily influenced Zoomer culture, a chopped-and-screwed, deep-fried, endlessly remixed creative tradition that dares its consumers to take anything too seriously. From the description on Filthy Frank’s YouTube channel:

Filthy Frank is the embodiment of everything a person should not be. He is anti-PC, anti-social, and anti-couth. He behaves and reacts excessively to everything expressly to highlight the ridiculousness of racism, misogyny, legalism, injustice, ignorance, and other social blights…[his show’s] terrible offensiveness is a deliberate and unapologetic parody of the whole social media machine and a reflection of the human microcosm that social media is. OR MAYBE IM JUST FUCKING RETARDED.

The unironic message here—that Filthy Frank intends to do something decent with his YouTube channel, even if the resultant art is fairly unpleasant—is undercut by the final sentence, which is itself an offensive 2000s-era eyeroll of a statement. I don’t doubt that Filthy Frank and iDubbbz—who is a vocal supporter of his wife’s OnlyFans, and who took her last name when the two married—are actually good people, and would probably make for fairly entertaining conversationalists IRL.

But their beat-you-to-the-punch-because-there-is-no-punch schtick is tired: I am too old to care about their bizarre microcelebrity, or the professionally-produced rap videos they make about their tedious feuds with other YouTubers. But when Belle Delphine takes this same brand of terminally online anti-humor and runs it through the glitter-drizzled CPU that is her pink-wigged, gamer girl persona? Pure dadaist magic.

Another unrelatable thing about Delphine: she’s twenty-four years old and has a net worth of roughly ten million dollars. She has been able to monetize her art in a way that’s almost unheard of among those not working with professional gallerists and curators.

She is known for her stunts. In 2019, recalling how many comments she regularly received on her posts and videos from guys professing their eagerness to drink her bathwater, Delphine decided to package and sell said bathwater for $30 a jar: her entire stock sold out within minutes. That same year, she promised her Instagram followers that if a certain post got one million likes, she’d start a Pornhub account. The post got over a million likes, so she made good on her promise, starting an account whose numerous videos had suggestive thumbnails and names like “Belle Delphine gets huge dripping CREAMPIE” and “Belle Delphine plays with her PUSSY.”

Watch these videos, though, and you’ll see a fully-clothed Delphine spraying a bunch of whipped cream into a pan and pieing herself in the face or appearing to reach into her underwear only to magically produce a stuffed toy kitten whom she then pretends to entertain with a squeaky donut. These trollings—about which her cis dude fans have expressed confusion, hurt and a sense of betrayal, emotions which I’m sure have sent them in droves to the paywalled content on her Patreon, Snapchat, and OnlyFans—combined with what her Wikipedia page calls a “surrealist eroticism of content” (see her YouTube videos in which she’s supposedly forgotten how to drink water, eats a raw egg, and cuddles with a dead pet octopus), elevate her above the realm of influencers whose palpable desperation for followers is often described as “clout-chasing.” Delphine is exploiting a simple truth known since time immemorial by sex workers and the generally kinky alike: there is immense power—and pleasure—to be had in subversion and denial. Or, put more simply: If you destroy it, they will come.

In purely aesthetic terms, Delphine and Marina Abramovic appear to be quite different: the former practically lives in her cosplay, wearing the eye-enlarging contacts, cat ears, and short skirts of a Lolita-esque anime character; the latter is quite severe by contrast, with a prominent nose, long black hair, deep red lipstick and the sort of intimidating adjacency to haute couture (and expensive material artifacts in general) shared by many aging artists and intellectuals who spent their childhoods behind the Iron Curtain.

But one need not dig that much deeper to begin seeing the similarities: the early years spent in isolation (Abramovic’s parents controlled her every move with a militaristic coldness, enforcing a 10pm curfew until she was 29), the strong associations with performance art (Delphine is frequently described as a performance artist by both her detractors and supporters; Abramovic is widely accepted as the “grandmother” of the form), the not-altogether-welcome influence of men on their artistic practice (viz. an underage Delphine stealing another model’s nudes and passing them off as her own at the behest of a man who said he could help her get rich online; Abramovic’s artistic collaboration and romantic relationship with German artist Ulay, a fruitful creative partnership whose emotionally fraught undertones would haunt them both long after their separation).

And for those adherents to the school of thought that would sooner pronounce the artist “dead” than consider their personal lives alongside their work: the similarities are in the work itself as well. Both women have an interest in the intersection of eroticism and defilement—in her nude pieces, Abramovic frequently underwent some form of self-inflicted torture, or else invited the audience to inflict that torture; Delphine goes the gross-out route, making her ahegao face in the midst of doing something disgusting like licking goopy raw meat or fondling an animal carcass—and both make art that very blatantly thematizes gender dynamics under patriarchy (see Abramovic and Ulay’s “Relation in Space,” and pretty much everything Delphine does, summarized in part by this music video, whose lyrics include: “trolling betas with my Pornhub…betrayer!”)

The similarities even extend to the kinds of objects used in the art: loaded guns and Russian roulette reoccur throughout a number of Abramovic’s performance pieces (she played her first game at age 14, accidentally destroying a copy of The Idiot on her parents’ bookshelf); this motif is echoed by Delphine in “Plushie Gun,” a video in which she pretends to shoot herself in the mouth with a rifle, get shot in the ass, and then licks a dildo-pistol. Skeletons also reoccur for both: in Abramovic’s Nude with Skeleton and Carrying the Skeleton—both inspired by her interest in Tibetan Buddhist rituals around death and mortality—and in Delphine’s “How to Become Belle Delphine,” which is not only my favorite video of hers, but perhaps one of my favorite YouTube videos of all time.

And while both Delphine and Abramovic have succeeded in making a neat mint off their intriguing, occasionally off-putting, and decidedly subversive art, the comparison between the two breaks down in one very significant way. Abramovic is considered one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, and was honored with a 2010 retrospective at MoMA that nearly a million people attended, but Delphine remains confined to the internet, forced to contest frequent social media bans due to the sexual nature of her content.

In 2019, she was banned from Instagram for the nebulous crime of “violating community guidelines.” In 2020, she was banned from YouTube and took to Twitter to express her bewilderment that popular recording artists like Cardi B. and 6IX9INE were not being banned for similarly explicit images in their videos.

Never mind the “highbrow” versus “lowbrow” distinction among artworks: anyone who’s spent any time on the internet—or, if you’re very lucky, a decolonized humanities classroom—knows that these so-called “indicators of taste” are just classist dog-whistles, and there’s just as much meaning to be found in Sailor Moon as in Hedda Gabler. And never mind the money, either—like I’ve said, both women have become very wealthy as a result of what they do, though Abramovic has a fairly extensive team looking out for her creative and financial interests, and it’s not altogether clear who else, if anyone, has a hand in helping perpetuate Delphine’s cottage industry of surreally erotic content.

What’s troubling is that Abramovic, who began as a self-proclaimed artist, is free to bob and weave between the categories of “intellectual” and “sex object,” often going so far as to assign herself one label or the other depending upon her mood, while Delphine, who began as a “model,” “gamer girl,” and “adult content creator,” is rarely if ever allowed to cross over into the realm of “artist,” a fact proven by the various suspensions of her social media accounts and a fan base whose critical and demanding nature has likely contributed to the long lapses in her online presence. This despite the fact that both women have successfully demonstrated how arbitrary the distinctions among art, porn, and pure provocation can be.

Marina Abramovic would not have been able to execute The Artist Is Present—a remarkable piece lasting the full length of her three-month-long MoMA retrospective during which she sat across from hundreds of thousands of patrons of the exhibit, gazing into their eyes for several minutes at a time—without the protection of her team, which included her assistant, her gallerist, the many young artists who re-enacted her earlier performance pieces, a large staff of security guards, and the considerable imprimatur of the MoMA itself.

Yes, Abramovic made herself bracingly available, but not without a safety net. But then what of artists like Delphine and other young e-girls, sex workers, and content creators? Why should they be tasked with fending for themselves? At what point are we compelled to draw a line separating the artists from the influencers, the self-portrait from the thirst trap? Why are we so determined to begrudge the thot her genius thoughts, thereby denying whole swaths of women and queers a hero whose genre-defying work has successfully weaponized our capitalist cisheteropatriarchy against itself.

*

In the HBO documentary about The Artist Is Present, curator and museum director Klaus Biesenbach’s purse-lipped description of Abramovic sounded fairly typical of the men in her life: “At first I thought she was in love with me,” he says, “but then I realized she is just in love with the world… she is always performing.” As Biesenbach went on to complain that it was difficult to tell what was and wasn’t a performance for Abramovic, I couldn’t help but think how both girlhood and womanhood under patriarchy are literally a constant performance, as well as how the philosophy of Judith Butler has reached enough of a critical mass that some of my undergraduate students who I know would balk at Gender Trouble’s dense, borderline-incomprehensible prose nevertheless have the phrase “gender is a performance” in their Discord bios. No shit, Biesenbach, I wanted to say. All of us who don’t look like you have been trained to dutifully perform for the benefit of those who do.

Being a woman in a culture which endlessly demeans and pathologizes you is itself a feat of endurance.And this is exactly what Abramovic is explicating in her Rhythm series—dosing herself with psychoactive drugs intended for schizophrenics and catatonics, or dancing nude and hooded for eight hours until collapse—that there is a terrifying barbarism lurking beneath the surface of “normalcy,” and that just being a woman in a culture which endlessly demeans and pathologizes you is itself a feat of endurance with results as violent and grotesque as many of her performance pieces.

Delphine is of course making a similar point, though her audience is not nearly as in on the joke, nor is she being recognized and applauded for it. Having been on both sides of the coin here—born a girl expected to wear makeup, flatter cis men, and maintain an “acceptable” weight and then transitioning into a Big Lebowski-meets-Birdcage chubby gay weirdo whose messy buffoonery isn’t just tolerated, but celebrated—my interest in Delphine-as-artist has only intensified.

Appearance-wise, I am farther now than I have ever been from whatever “feminine ideal” her gamer dude fans imagine she embodies, but watching her videos makes me feel closer than ever to my own experience of femininity—which is to say, womanhood-as-performance, or womanhood-as-irony. Cishet sex not as a genuinely pleasurable activity, but an occasion for a comic ahegao face. My own “prettiness” less something deeply felt than an elaborate “girl” cosplay: my eyelashes, cleavage, and desire for cis men all laughably fake. And this is how Delphine manages to thematize the strange quagmires of both womanhood and transness at once.

The fact of the matter is that Belle Delphine’s art has had as great an influence on my own self-discovery as more “traditionally” queer and/or trans texts like Stone Butch Blues, The Argonauts, and Zami. It was through her content creation that I was able to look back at my own life through a glass snarkily, and for that reason I feel as indebted to her as the patrons who broke down crying during The Artist Is Present do towards Abramovic. This is why “Like and Subscribe” is far more than just slashfic (the Delphine character naturally turns out to be gay) or a fan letter for me: it’s a merging of the two that’s really a platonic love note, my way of imagining a world in which Delphine is allowed to be as candidly and chaotically herself as any young woman her age—a world in which she is allowed to be present.

In “How to Become Belle Delphine”—which is both ribaldly funny and as close to a personal essay as anything she has ever produced—the artist sets out to transform her plastic “friend” Mr. Skeleton into herself, thus completing a kind of self-portrait in Nerds, raw eggs (a favorite medium of hers), and raw chicken breast, among other things. After reassuring us that she is, indeed, a licensed doctor, she packs a vaginal-looking raw turkey “heart” with “glittery gloop” and a small statue of the Virgin Mary (both intended as protection against “evil fuckbois”).

She then goes on to reveal that she’s storing Mr. Skeleton’s organs in Brock Turner’s skull (which is “small and broken, but a good place to hold your slime”), cover a tiered tray of cupcakes in what may be expired veal cutlets, and produce her fake AK-47 only to intone with standard Zoomer drollery: “No, we’re not going to school today!” Interspersed with moments like these are others about the absurdity of living and dying by one’s follower count, the burden of parental expectations, the male gaze in digital form, and even the persistence of traumatic memories (as represented by a collection of razor blades lodged in the gelatinous chicken breast).

Is this a work of art that a curator like Biesenbach should display in the Met, Guggenheim, or MoMA, worthy of the same critical attention afforded the grandmother of performance art herself? Or even the critical attention that’s been afforded me, a non-celebrity, early-career writer who’s nevertheless publishing with a Big Five press? My answer to both is of course yes, though I wonder if Delphine would roll her eyes at the imprimatur of the art world and the moneyed old fogeys therein, contest its ability to “legitimize” any of her content and dismiss its fundamental fuckboi energy with an uwu and spirited cackle.

After all, is Biesenbach’s weird cathexis on Abramovic that much different from the obsessive and demanding stream of dick pics and vitriol that floods Delphine’s various inboxes daily? Is it really any better to be the darling of the art world than it is to cheerfully troll betas all the way to the bank? Or is seeking legitimacy from the likes of Biesenbach just another classist, patriarchal trap?

Regardless of where Delphine may fall on these issues, I know one thing for sure: I want her to be able to be herself, and I want her to feel safe doing so. As an artist/e-girl/adult content creator, she’s managed to change the rules of the game she first set out to play: in fact, like many a truly visionary creative mind, she seems to be innovating the entire concept of the game itself. For this reason, she deserves the right to create an oeuvre: whether her videos are destined to be projected onto gallery walls or simply serve to increase her follower count, all bans on her social media presence should be lifted and never reinstated. Whether those consuming her art are doing so out of horniness or pure artistic appreciation or (as I’m sure is frequently the case) a combination of both, Delphine is at the bleeding edge of comic vanguard whose anti-patriarchal gender fuckery is well deserving of many a like and subscribe.

A very perceptive reader of an early draft of this essay pointed out that some may interpret my defense of Delphine’s art as a form of mansplain-y condescension: I am the Travis Bickle who has decided to repurpose his out-of-control horniness into a “heroic” defense of the sex worker with the heart of gold. Such a reader might think that, in categorizing Delphine’s content as “art,” I am merely imposing my puritanism on her as a means of skirting my own sense of shame. The idea being that a man of my tastes wouldn’t spend hours watching something as base and disgusting as porn—therefore, Delphine must be an artist, and the anime-orgasm faces and revealing “fits” must be her art.

I will admit to being slightly shocked when I first received this feedback, though upon further reflection it made perfect sense: I am, after all, a man now—or at the very least, people perceive me as such. And were someone to tell me that a thirty-four-year-old male writer had penned a nearly 4,000-word encomium to an e-girl ten years his junior, I would be totally squicked out. One of the many strange things about being trans is the fact that eventually people start perceiving you as the gender you’ve gone to such pains to emulate. After those many months or years of correcting peoples’ pronoun usage and inspecting the HRT’s effects in your bathroom mirror, the world suddenly catches up, and then it’s you who has to remember to correctly gender yourself.

And so we enter once again the genderqueer mise-en-abyme that the work of thought (or thot) leaders like Delphine and Abramovic beckons us into. As far as sexual attraction goes, I feel none whatsoever towards Delphine: for a whole host of personal reasons, including how young she is and the bare facts of my own preferences, she is not someone who would ever scan as “object of desire” for me.

I feel more a sense of protectiveness towards her, less Bickle-esque than a simple interest in encouraging her creativity, the way I feel whenever I encounter some truly stunning work by one of my students. But beyond that, I also identify with her. Her campy, eyeroll approach to standards of feminine beauty, her transformation of men’s slavering desire into a generous income stream: I find it laudable, and see a liberated version of my own girl-self therein.

Let’s step back and take a moment to consider that this text was written by a man about an e-girl whose videos remind him of when he was a girl, to promote the publication of his short story collection that contains a slashfic in which the man imagines a queer relationship for that e-girl (and thereby his own girl-self) that functions as liberation from the compulsory heterosexuality that plagued his own girl-days (and perhaps also the e-girl’s, though that’s just speculation).

We are truly through the looking glass here gender-wise, which is the kind of tomfoolery I hope to accomplish with my own art anyway. And this is one of the many wonderful things about being trans, this idea of “crossing lines.” The transgression can be both aesthetic and political, sure, but it’s also metaphysical in the sense that you feel you’ve suddenly hopped from one life to another, split apart into a billion different people and then reconstituted again as a single person, though with many more valences: both yourself and not, bearded queer dude and winking anime kitten at once.

__________________________________

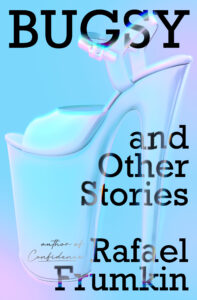

Bugsy & Other Stories by Rafael Frumkin is available from Simon & Schuster.