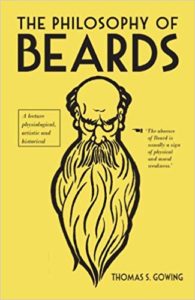

The Argument We Need for the Universal Wearing of Beards

Cutting Edge Victorian Tastemaker Thomas S. Gowing Says Let it Grow

The Beard, combining beauty with utility, was intended to impart manly grace and free finish to the male face. To its picturesqueness, Poets and Painters, the most competent judges, have borne universal testimony. It is indeed impossible to view a series of bearded portraits, however indifferently executed, without feeling that they possess dignity, gravity, freedom, vigor, and completeness; while in looking on a row of razored faces, however illustrious the originals, or skillful the artists, a sense of artificial conventional bareness is experienced.

Addison gives vent to the same notion, when he makes Sir Roger de Coverley point to a venerable bust in Westminster Abbey, and ask “whether our forefathers did not look much wiser in their Beards, than we without them?” and say, “for my part, when I am in my gallery in the country, and see my ancestors, who many of them died before they were of my age, I cannot forbear regarding them as so many old Patriarchs, and at the same time looking upon myself as an idle smock-faced young fellow. I love to see your Abrahams, your Isaacs, and your Jacobs, as we have them in the old pieces of tapestry, with Beards below their girdles that cover half the hangings.” The knight added, “if I would recommend Beards in one of my papers, and endeavor to restore human faces to their ancient dignity, upon a month’s warning he would undertake to lead up the fashion himself in a pair of whiskers.” In reference to this last allusion it may be as well to state, that the word whisker is frequently used by earlier authors to denote the moustache, and that in Addison’s time, a mass of false hair was worn, and the head and face close shaven.

To shew that it is the Beard alone that causes the sensation we have alluded to, look at two drawings on exactly the same original outline, of a Greek head of Jupiter, the one with, the other without the Beard! What say you? Is not the experiment a sort of “occular demonstration” in favor of nature, and a justification of art and artists? See how the forehead of the bearded one rises like a well-supported dome—what depth the eyes acquire—how firm the features become—how the muscular angularity is modified—into what free flowing lines the lower part of the oval is resolved, and what gravity the increased length given to the face imparts.

As amusing and instructive pendants, take two drawings of the head of a lion, one with and the other without the mane. You will see how much of the majesty of the king of the woods, as well as that of the lord of the earth, dwells in this free flowing appendage. By comparing these drawings with those of Jupiter, you will detect, I think, in the head of the lion whence the Greek sculptor drew his ideal of this noble type of godlike humanity.

Since this idea struck me, Mr. John Marshall, in a lecture at the Government School of Practical Art, has remarked, “that nature leaves nothing but what is beautiful uncovered, and that the masculine chin is seldom sightly, because it was designed to be covered, while the chins of women are generally beautiful.” This view he supported by instancing, “that the bear, the rabbit, the cat, and the bird, are hideous to look upon when deprived of their hairy and feathery decorations: but the horse, the greyhound, and other animals so sparingly covered that the shape remains unaltered by the fur, are beautiful even in their naked forms.”

This argument, it seems to me, applies with greater force to the various ages of man. In the babe, the chin is exceedingly soft, and its curve blends into those of the face and neck: in the boy it still retains a feminine gentleness of line, but as he advances to the youth, the bones grow more and more prominent, and the future character begins to stamp itself upon the form: at the approach of manhood, the lines combining with those of the mouth become more harsh, angular, and decided; in middle age, various ugly markings establish themselves about both, which in age are rendered not only deeper, but increased in number by the loss of the teeth and the falling in of the lips, which of course distorts all the muscles connected with the mouth.

There is scarcely indeed a more naturally disgusting object than a beardless old man.

Such, however, is the force of prejudice founded on custom, that people who sink themselves to the ears in deep shirt collars, and to the chin in starched cravat and stiffened stock, muffle themselves in comforters till their necks are as big as their waists; nay do not demur some of them to be seen in that abomination of ugliness—that huge black patch of deformity—a respirator, have still sufficient face left to tell us that the expression of the countenance would be injured by restoring the Beard!

A word, therefore, on the expression of Bearded faces. The works of the Greeks, the paintings of the old Masters, but above all the productions of the pencil of Raphael, justly styled “the Painter of Expression,” is a sufficient general answer to this ill-considered charge. It would indeed be strange if He who made the male face, and fixed the laws of every feature—clothing it with hair, as with a garment, should in this last particular have made an elaborate provision to mar the excellency of His own work!

Nothing indeed but the long effeminizing of our faces could have given rise to the present shaven ideal—to the forgetfulness of the true standard of masculine beauty of expression, which is naturally as antipodal as the magnetic north and south poles, to that of female loveliness, where delicacy of line, blushing changeable color, and eyes that win by seeming not to wish it, are charms we all feel, and at the same time understand how inappropriate they are when applied to the opposite sex; where the bold enterprising brow—he deep penetrating eye—the daring, sagacious nose, and the fleshy but firm mouth, well supported on the decided projecting chin, proclaim a being who has an appointed path to tread, and hard rough work to do, in this world of difficulties and ceaseless transition.

So much for the general charge; if we examine the separate features, there can be no question that the upper part of the face—the most godlike portion—where the mind sits enthroned, gains in expression by the addition of and contrast with the Beard; the nose also is thrown into higher relief, while the eyes acquire both depth and brilliancy. The mouth, which is especially the seat of the affections, its surrounding muscles rendering it the reflex of every passing emotion, owes its general expression to the line between the lips—the key to family likeness; and this line is more sharply defined by the shadow cast by the moustache, from which the teeth also acquire additional whiteness, and the lips a brighter red. Neither the mouth nor chin are, as we have said, unsightly in early life, but at a later period the case is otherwise.

There is scarcely indeed a more naturally disgusting object than a beardless old man (compared by the Turks to a “plucked pigeon”) with all the deep-ploughed lines of effete passions, grasping avarice, disappointed ambition, the pinchings of poverty, the swollen lines of self-indulgence, and the distortions of disease and decay! Now the Beard, which, as the Romans phrased it, “buds” on the face of youth in a soft downiness in harmony with immature manliness, and lengthens and thickens with the progress of life, keeps gradually covering, varying, and beautifying, as the “mantling ivy” the rugged oak, or the antique tower, and by playing with its light free forms over the harsher characteristics, imparts new graces even to decay, by heightening all that is still pleasing, veiling all that is repulsive.

The color of the Beard is usually warmer than that of the hair of the head, and reflection soon suggests the reason: The latter comes into contact chiefly with the forehead, which has little color; but the Beard grows out of the face where there is always more or less. Now nature makes use of the colors of the face in painting the Beard—a reason by the bye for not attempting to alter the original hue, and carries off her warm and cold colors by that means. Never shall I forget the circumstance of a gentleman with high colour, light brown hair, full whiskers of a warm brown, deepening into a warm black, and good looking, though his features, especially the nose, were not regular—taking a whim into his head to shave off his whiskers. Deprived of this fringe, the color of his cheeks looked spotty, his nose forlorn and wretched, and his whole face like a house on a hill-top exposed to the north east, from which the sheltering plantations had been ruthlessly removed.

The following singular fact in connection with the color of the Beard, I learnt in chance conversation with a hairdresser. Observing that persons like him with high complexion and dark hair, had usually a purple black beard: he said, “that’s true, sir,” and told me he had “found in his own Beard, and in those of his customers, distinct red hairs intermingled with the black,” just as it is stated that in the grey fur of animals there are distinct rings of white and black hairs. This purplish bloom of a black Beard is much admired by the Persians; and curiously enough they produce the effect by a red dye of henna paste, followed by a preparation of indigo.

There is one other point connected with color which ought not to be omitted. All artists know the value of white in clearing up colors. Now let any one look at an old face surrounded by white hair, whether in man or woman, and he will perceive a harmonizing beauty in it, that no artificial imitation of more youthful colors can possibly impart. In this, as in other cases, the natural is the most becoming.

Permit me to conclude this section of my lecture by reminding all who wish to let their Beards grow, that there is a law above fashion, and that each individual face is endowed with its individual Beard, the form and color of which is determined by similar laws to those which regulate the tint of the skin, the form and color of the hair of the head, eyebrows, and eyelashes; and therefore the most becoming, even if ugly in itself, to their respective physiognomies. What suits a square face, will not suit an oval, and a high forehead demands a different Beard to a low one. Leave the matter therefore to nature, and in due season the fitting form and color will manifest themselves. And here parties who have never shaved have this great advantage over those who have yielded to the unnatural custom, that hair will only be visible, even when present, in its proper place, be better in character and color, and more graceful in its form.

__________________________________

From The Philosophy of Beards by Thomas S. Gowing. Used with permission of Melville House Books. Copyright 2019.

Thomas S. Gowing

Thomas S. Gowing is the author of Normal Schools: And the Principles of Government Interference with Education and the eccentric Victorian book The Philosophy of Beards..