As he did every morning, Antoine was looking, not simply at Rachel, but at her everyday ritual: the crinoline dress, the parasol in her right hand, the basket in her left, the smile on her face, the song from her lips. Her dazzling beauty. Her everyday ritual, because, in early summer, Rachel invariably appeared at precisely the same time, in precisely the same manner; she would walk slowly from the square next to Les Halles to the Hôtel de Ville, pass the headquarters of the learned society, greeting the scholars—if by chance she encountered any—with a flourish of her parasol; she would turn onto the rue des Tribunaux, stroll past the Palais de Justice, turn left onto the rue du Tourniquet toward Notre-Dame, which she would circle before taking the rue de la Cure, past the barracks of the gendarmerie on the rue de la Motte-du-Pin to the corner of the road heading west toward Ribray. She would walk down to the river and amble past the gardens of the prefecture and the château to the rue Brisson and the covered market, where she would greet the butchers, the dairymen and the customers, before taking the rue Civique up past the town hall, and so on. This peregrination, undertaken with the elegant gait of a young lady, pausing to greet every person she met, even crossing the street to do so, took at least three-quarters of an hour. On market days, Antoine noted, she would continue walking from nine o’clock until midday, or, in other words, according to Antoine’s calculations, six or seven circuits in a single morning.

Sometimes, she would walk along the river Sèvre as far as the Jardin des Plantes in the late afternoon, when the bourgeoisie emerged to take the air; it was a lovely walk, the rippling reflections, the roses and the wisteria, the daffodils and lilacs. Rachel was a flower seller; beautiful sprays of fresh flowers in summer, magnificent dried bouquets in winter.

Antoine’s shop stood on the corner of the place des Tribunaux, so he could watch Rachel’s progress at his leisure while he repaired wooden clogs and punched holes for ladies’ boots. Antoine was unfamiliar with Halévy’s aria from La Juive, “Rachel, quand du Seigneur . . .”; had he not been, he would have sung it all day long as he worked. Antoine dared not speak to Rachel beyond a curt “hello” as she passed his workshop. He was happy simply to watch. He knew everything about her—her slender waist, her ample breasts, the little black boots that hugged her ankles like gloves, eyes that you might see in a picture gallery set into a perfect face. But more than her sublime body, what drove poor Antoine crazy with love was Rachel’s voice. It had a unique timbre, a fullness, a huskiness that was so melodious. Antoine would sometimes hear her hum as she passed his window; he longed for her to sing for him, every morning, every evening, and he cared little what she might have to say since, with such a voice, she could say anything she pleased and Antoine would listen, spellbound.

Of course, Rachel was entirely unaware of the passions she stirred in Antoine; she had noticed the cobbler’s gallantry whenever she crossed the place des Tribunaux, but all the good citizens of Niort were chivalrous to Rachel—they bought her flowers; while the bourgeoisie, the merchants and the dignitaries purchased other favors for a moderate fee, and, they believed, far from prying eyes. Unsurprisingly, Antoine was blind and deaf to those things that, had they reached his ears, he would have dismissed as ugly jealous rumors; but, in truth, no one knew—Rachel paraded her beauty throughout the city; from time to time, she could be seen in a phaeton or a cabriolet drawn by a pair of thoroughbreds next to an immaculately dressed gentleman, heading, no doubt, to picnic at La Roussille in the shade of the great plane tree by the river, an innocuous day in the country, all pretty fabrics and rakish hats. That all these suitors were already married did not trouble Antoine, since he did not know. Not that he was credulous, but he was blinded his tender, heartfelt love for Rachel. He spent his days working with awl, needle and scissors; Saint Crispin, patron saint of cobblers, looked kindly upon him, and his business was thriving. Excellent, inexpensive leather was to be found in Niort, a city of tanners. Pigskin and calf leather made beautiful shoes, with fine hardwood heels. Ah, had he but dared, he would have suggested that Rachel come into his shop, where he could measure her delicate feet, and for her fashion a splendid pair of little boots. But he had never dared. Many a time as he watched her pass he would say to himself, Tomorrow. Tomorrow, without fail, I shall speak to her . . . but when tomorrow came, he would merely greet her politely, as he had done yesterday and the day before, cursing the march of the seasons and the looming autumn bleakness that would deprive him of the quotidian pleasure of Rachel’s smile.

One early September day shortly before summer’s end, when Niort reeks of sludge and fish oil, when the waters beneath the bridges ebb, when it seems the Marais marshland, with its gnats and dragonflies, has risen to engulf the town, Rachel stepped into Antoine’s shop for the first time. It took him all the strength he could muster to mask his agitation. He listened as she spoke (or rather allowed himself to be lulled by her singular voice, a little husky, almost injured) and spluttered some inanity in response. He was shaking. He swiftly took the proffered shoes. This is the design? Yes, that is the design. Let me just measure your left foot. Often the left foot is the larger. Please don’t laugh, a person’s feet are never identical, as any cobbler will tell you. Even Antoine had begun to despair of his inanities. He wished he might be witty and charming. Rachel was gentle, and redolent of cinnamon and forget-me-nots. She was smiling. She wore a white dress trimmed with red, whose swooping neckline afforded a glimpse of her bosom. Antoine had to let her leave. He wished that he might marry her. She will come back to collect the shoes. I shall make the most beautiful pair of boots the world has ever seen. Antoine was eager to set to work. For Rachel.

He heard two loud, sharp cracks, like timbers falling from a height. Puzzled, he raced outside; Rachel lay sprawled across the steps of the Palais de Justice; an orderly was struggling to overpower a woman who was waving a revolver and howling, she looked distraught, her mouth was vast and monstrous. Antoine recognized the vulgar, hateful face of Gabrielle, the wife of the court clerk. The orderly had managed to wrest the gun away and was staring at it incredulously, like a tomfool. Antoine sank to his knees and took Rachel in his arms; her breath was faint, the ghastly soft hiss of a ball deflating; a sticky warmth spread over Antoine’s belly and his thighs. Antoine held Rachel and crooned: my love if it pleased you, we could sleep side by side . . . My love if it pleased you. Until the world should end. Until the world should end.

__________________________________

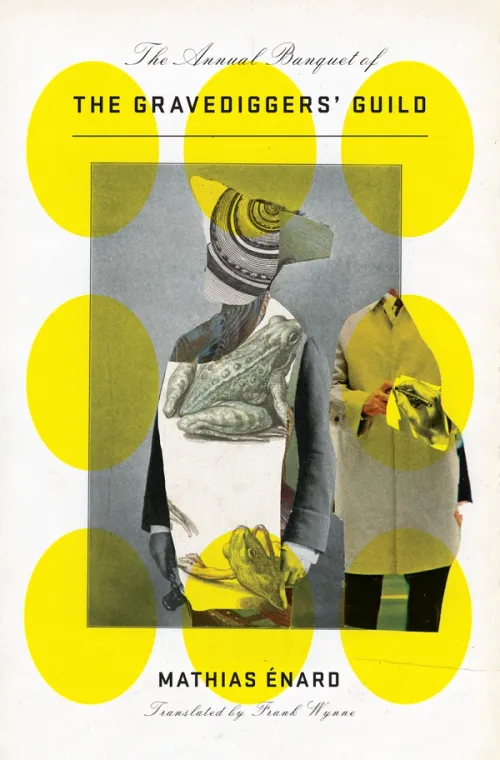

Excerpt from The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild, copyright 2020 by Mathias Énard, Translation copyright © 2023 by Frank Wynne. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing.