The Annotated Nightstand: What Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta is Reading Now and Next

A New (at Lit Hub) Series by Diana Arterian

Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta’s first book, The Easy Body, was one I fell into immediately. “Got tired of being a house on fire,” she writes, “so I became a poet.” In their second book La Movida (out earlier this month from Nightboat), they write, “The dancing water / replaced my tongue with a knife.” These are the shifts I so often find myself drawn to in poetry. Crackling images, with language as a means to become something more empowered. Luboviski-Acosta attends to violence, conflict, maternity, isolation, so much else in their first collection.

In La Movida, the poems dive more explicitly into family, family history, and mythology—their father’s death, their inherited trauma of the Dirty War, the claim that an they’re related to Che Guevara’s first wife. “If you can’t already // tell,” they write, “my entire last name is a narrative of aban / donment—it could have been worse.” Beyond this, Luboviski-Acosta attends to their sexuality, gender, love and desire (at times cheekily). In one of my favorite pieces, entitled “Young God,” they compare the extremity of their desire to a deity’s. They write:

Look around you,

I have become a flood.

All things in my path

have found themselves

destroyed.

You took my hand.

Luboviski-Acosta is also a visual artist. Like in The Easy Body, Luboviski-Acosta includes their visual art interspersed with their poetry in La Movida. Where art in The Easy Body, was collage, the latest collection includes stark black-and-white painted pieces. There is a figure with breasts, braids, a semi-automatic rifle on their shoulder, and a large horse mask crowned with flowers. A nude human figure rides a humanoid spotted cat’s muscled shoulders.

*

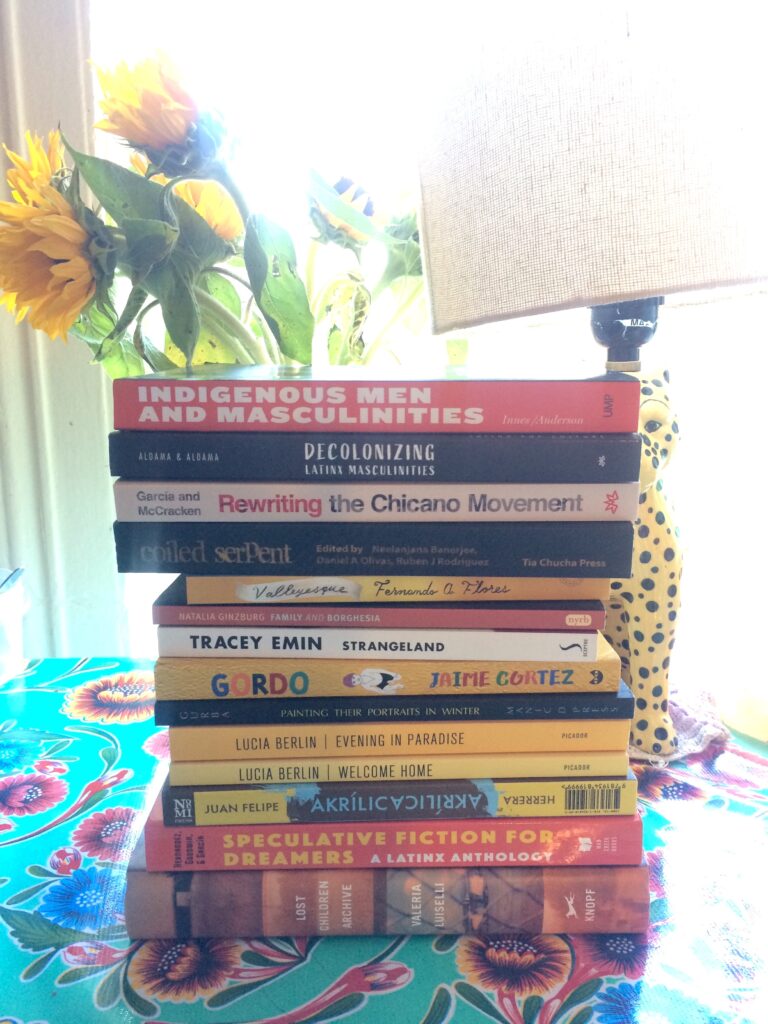

Robert Alexander Innes & Kim Anderson (eds.), Indigenous Men and Masculinities: Legacies, Identities, Regeneration

This collection attends to the topic of its title, but from a perspective that makes it a particularly compelling book. The jacket copy states: “What do we know of masculinities in non-patriarchal societies? Indigenous peoples of the Americas and beyond come from traditions of gender equity, complementarity, and the sacred feminine, concepts that were unimaginable and shocking to Euro-western peoples at contact… Indigenous Men and Masculinities highlights voices of Indigenous male writers, traditional knowledge keepers, ex-gang members, war veterans, fathers, youth, two-spirited people, and Indigenous men working to end violence against women. It offers a refreshing vision toward equitable societies that celebrate healthy and diverse masculinities.”

Arturo J. Aldama & Frederick Luis Aldama (eds.), Decolonizing Latinx Masculinities

Considering the attention Luboviski-Acosta gives to gender in their work, it’s not surprising there are multiple texts that address it directly in their pile. This edited collection considers more specifically the cultural impacts of capitalism in conjunction with Latinx masculinity (what’s been fed to us on television and film for decades, what pops up on social media). Beyond this, however, some of the contributors explore the nourishing and “healing masculinities,” including queer Latinx rodeos, food, music, and more.

Mario T. Garcia & Ellen McCracken (eds.), Rewriting the Chicano Movement: New Histories of Mexican American Activism in the Civil Rights Era

As the title suggests, this collection of essays attempts to give further nuance to the most powerful civil rights work enacted by Mexican Americans up until that time in the United States. “The essays in this volume broaden traditional views of the Chicano Movement that are too narrow and monolithic,” as the book’s description states. Also known as “El Movimiento,” the Chicano Movement involved thousands of activists fighting for civil rights denied them since the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, and claiming Chicano identity as one of empowerment. The contributors to this collection give insight into the many varied members and methods of activism otherwise left out of the history books.

Neelanjana Banerjee, Daniel A. Olivas, Ruben J. Rodriguez (eds.), Coiled Serpent: Poets Arising from the Cultural Quakes and Shifts of Los Angeles

This amazing collection includes LA poets such as Wanda Coleman, Vickie Vertiz, Amy Uyematsu, Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo. In his introduction to this collection, then-Poet Laureate Luis Rodriguez writes, “For me, Los Angeles is smoldering, deeply poetic, expansively settled, with rebellion beneath the normalcy, which has un chingo to do with our collective and personal spiritual awakenings, creative birthings, political schooling—why our lives are in flames… The coiled serpent is connected to the earth, but also ready to spring, to strike, to defend or to protect.”

Fernando A. Flores, Valleyesque

Flores sets his short story collection on the border between Mexico and Texas—but with the fantastical as a continual presence. In her review for the New York Times, Jean Chen Ho focuses on one particular short story, “Nocturne From a World Concave,” which stars the Romantic composer Chopin. Ho explains, “In Ciudad Juárez, a terminally ill Frédéric Chopin marks his last days in a shabby apartment near the market square. The renowned composer, or ‘Papá Chopin,’ as the children in the street call him… After an unsuccessful attempt to recover his confiscated Pleyel piano, Chopin is detained by a pair of handsomely dressed goons. They pull a luchador mask over his head—the eyes and mouth sewn shut—and throw him in a pickup truck.” To learn Chopin’s fate, you must read the rest.

Natalia Ginzburg,(trans. Beryl Stockman), Family & Borghesia

These two novellas focus on two domestic situations with remarkably different concerns. Both are set in 1970s Italy—one with a man’s second marriage (but attention to his first wife), the second a widow who, fending off loneliness, finds (and loses) many Siamese cats. “The two have many elements in common,” writes Lynne Sharon Schwartz for the Los Angeles Review of Books. “It is as if Ginzburg assembled a batch of ingredients and whipped up two different dishes out of them. One turned out to be a superb, unforgettable feast, while the other turned out fine, nourishing, as everything Ginzburg wrote is fine and nourishing.”

Tracey Emin, Strangeland: The Memoirs of One of the Most Acclaimed Artists of Her Generation

The Romani-Cypriot-British artist Tracey Emin made remarkable impacts on the British art scene, particularly in the 1990s. Her media includes paint, photography, sculpture, film, neon, fabric. One notably famous piece was a zip tent the viewer entered that Emin had appliquéd with bold, colorful names of all those with whom she shared a bed (either in the chaste childhood fashion or sexual encounters). It was entitled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With (1963-1995), and included her exes, familymembers, and the two fetuses she had aborted. The book includes her attempts to reconnect with her estranged father in Turkey, her difficult childhood, a botched abortion—her life rather than the specifics of her art.

Jaime Cortez, Gordo

This short story collection is set in 1970s Watsonville—a town in California. The stories are often told from the perspective of Gordo, a child of Mexican immigrants who live and work in Watsonville. Gordo is a bit of an outsider, who is mocked by the other kids. In the NPR review of the book, Michael Schaub praises “Cortez’s ability to fully inhabit the voice of a young boy who knows he doesn’t fit in, but is only beginning to understand why.”

Myriam Gurba, Painting Their Portraits in Winter

Gurba is now largely known for taking down the racist-but-too-big-to-fail book American Dirt, and even getting its publisher Flatiron Books to sit down with Gurba and other activist authors to promise more diversity and consideration and care in their process. I’ve been obsessed with Gurba’s novel Mean since I first read it, and crave her sharp humor and philosophy (maybe one of the only people I have read who can keep those plates spinning so elegantly). Of this collection, Gurba states, “The stories deal with the supernatural feminine and the supernatural feminist big time. They explore misogyny and they channel misogynistic ghosts. Death lurks around every comma. There is also a lot of fruity symbolism.”

Lucia Berlin, Evening in Paradise and Welcome Home: A Memoir with Selected Photographs and Letters

Reading descriptions of these two books makes me want to go out and read Berlin right away. She led a wild life of travel (mining towns as a child, Chile as a teen, the Bay, New Mexico, Mexico City—it goes on). Her wayward relationships, struggles with alcoholism, and careful eye for characters all impact her writing, as do her many homes during her life. In a review of Berlin’s memoir, Jordan Kisner at The Atlantic writes, “It’s no accident that many critics looking for Berlin’s peers compare her primarily to male authors (Hemingway, Raymond Carver), though the comparisons rarely do justice to her humor or her quirky, lavish prose style.” Berlin, unfortunately, seemed to have received her acclaim only after her death in 2004. Evening in Paradise was named a Best Book and its variants by almost two dozen journals.

Juan Felipe Herrera, Akrílica (ed. Farid Matuk, Carmen Giménez, Anthony Cody)

As an editor at Noemi Press, I was thrilled to see one of our books in Luboviski-Acosta’s stack! This is a book we have been excited about for some time, particularly because we have named an entire portion of our press “Akrilica Series” to honor Herrera’s totemic work. This is a revisiting/publishing of a collection originally published in 1989, with new interviews, a visual introduction, as well as archival material to further enrich the reader’s understanding of the context of the work. The synopsis states, “We steal Akrílica away from literary institutions, away from the discipline of literature as such, and away from traditions of experimental poetics that should hope to claim it.”

Alex Hernandez, Matthew David Goodwin, and Sarah Rafael García (eds.), Speculative Fiction for Dreamers: A Latinx Anthology

This extension of the 2020 collection Latinx Rising, this collection is, according to its publisher, “unified by their drive to imagine new Latinx futures, these stories address the breadth of contemporary Latinx experiences and identities while exuberantly embracing the genre’s ability to entertain and surprise.” It’s broken into five titled sections: “Dreaming of New Homes,” “Dreams Interrupted,” “My Life in Dreams,” “When Dreams Awaken,” and “Dreams Never Imagined.” Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review, and states, “This is a knockout.”

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive

Luiselli wrote and published the powerful book-length essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions, which chronicles her experiences as a volunteer interpreter for children immigrating into the US to flee violence, hunger, or with their families’ hopes for a different life. This alongside the impact of their travels, ICE detention, and the bureaucracy that generally shields the United States from accounting for these children—and the multitudinous ways in which the US created the gang violence from which the children flee. Lost Children Archive attends to this topic from a place of fiction. In her review of the novel for NPR, Heller McAlpin states, “Read together with Tell Me How It Ends, Luiselli’s third novel is, among other things, a fascinating demonstration of the interplay between fiction and nonfiction—and a window into how a writer can forge two very different books from the same raw material.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.